URI INSPECTOR reviews UCL Drama Society’s production of Rhinoceros.

Eugène Ionesco’s satire on political populism uncannily resembles recent events. Written in response to the rise of communism and fascism in the years leading up to the Second World War, Rhinoceros depicts a world in which the foundations of logic and truth are relentlessly dismantled, and in which militant mass movements are born, fuelling prejudice, violence and social unrest. Sound familiar?

In a provincial town riddled by a disease (‘rhinoceritis’) which transforms its sufferers into rhinos, people really have – as prominent Brexiteer Michael Gove once put it – ‘had enough of experts’. ‘I don’t believe journalists’, squawks Botard (Maciej Mańka), coneying the bitterness of the disgruntled. Jean (Sam Pryce) is likewise a character who embodies blind prejudice and ‘post-truth’, ranting about doctors inventing diseases. The only respected source of knowledge in the town is a senseless hack called ‘Logician’ who speaks purely in non-sequiturs, and is skilfully styled as a millennial street urchin in this production. ‘Unbelievable!’ scream the civilians when the rhinos first romp through town; but then the rhinos become absurd ‘little aberrations’, and then confusing and hilarious, with hopeless wives clinging to the shoulders of husbands-turned-rhinos. Over time, they are socially accepted, and absorbed into the mainstream. Meanwhile, ordinary people are too distracted by pedantry and sentimentality to discuss the real root of the problem, instead lamenting the deaths of cats or musing on the differences between Asian and African rhinos.

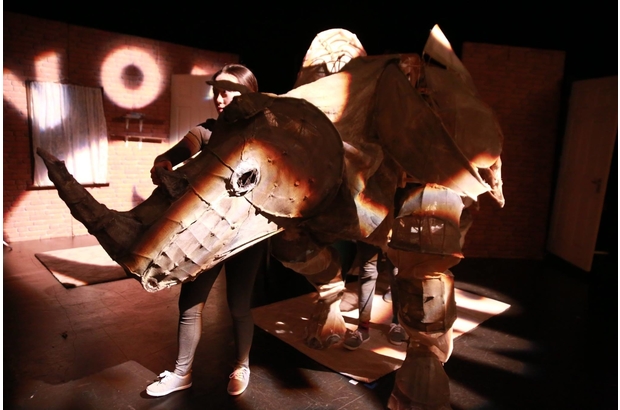

The play’s opening scene combines the absurd with the everyday. Thoughtful set design contrasts a quaint provincial café with the grey monstrosity of a giant rhinoceros puppet, who charges across the stage controlled by a team of handlers (Marian Li, Sian Robbins and Lovis Maurer). While Berenger (Erik Alstad), the play’s outcast protagonist, attempts to question the meaning behind this, his confusion falls on the deaf ears of a hilarious and energetic ensemble who are engaged in meaningless discussion. Placing the first interval after the very first scene seems premature, but it also allows the audience to digest the lunacy of what we have witnessed, while rendering the action of the next act all the more explosive.

The puppet beast, constructed from plywood and cane, commands the stage at the play’s climactic points with its sheer enormity. Its handlers convey its mannerisms with subtle detail, making it both uncanny and captivating. During the play’s second interval it stands proud and menacing on the stage, firmly establishing the turning point at which rhinos begin to dominate Berenger’s surroundings.

Funnily enough, it is those who are oversensitive or feel rejected who are most susceptible to transform into the ironically thick-skinned pachyderms. The fragile ego of self-righteous Jean – half Peep Show Mark Corrigan, half ex-UKIP leader Nigel Farage – is masterfully evoked by Pryce, who vacillates effortlessly between comedy and menace. He is contrasted with Erik Alstad’s brilliantly eccentric Berenger, whose nervous energy commands the attention of the audience. Directors Matthew Neubauer and Matt Aldridge move the action on and off stage, concealing and revealing, to heighten the tension until Jean finally transforms into a rhino. Meanwhile, Alstad powerfully evokes Berenger’s trajectory from charming misfit to obsessive hypochondriac, with moving and thoughtful renditions of Ionesco’s long monologues.

The production makes a marvellous use of music, contrasting charming French café jazz with the primitive drumming accompanying the rhinos. Perhaps the most thrilling moment is the opening of act 3, when a glamorous rock band comes on stage to deliver a caustic rendition of Black Sabbath’s ‘War Pigs’, which thunders in the back of a montage of violence. The sonic and visual brutality of this scene conveys the chaos of mob mentality and provides necessary variety to scenes, which are often heavy with philosophical discourse.

Great performances sustain the crazed energy of Ionesco’s text, with ensemble scenes suitably outrageous and lively. Berenger’s final, difficult monologue is both intimate and disturbing. Laura Pieters’ Daisy provides an effective foil to Berenger’s neurosis, while James Fairhead’s Dudard vividly displayed the sourness of his unrequited love for her. One moment hysterical, the next unsettling; UCL Drama Society have created a production which joyfully evokes Ionesco’s absurdism at a time when we need it most.

Rhinoceros ran at the Shaw Theatre from 2nd -4th March. Find more information about the production, see here.

Featured image courtesy of Dante Kim.