CHRISTINA LIBRI considers tokenism in the art world through the canonical status of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

In the past, the Black Lives Matter movement has been characterised by large swells of short-term support. Unfortunately, this mass engagement tended to die down after a month or two, meaning the promotion of anti-racism had a trend-like viral presence. In 2020, the most powerful message put across by the movement was the importance of ‘educating yourself’ in order to help bring about long-lasting and sustainable change. So I, an art history student, began to reflect on myself and my interests.

Artists have always been at the forefront of social change. But artists, despite being its very foundation, do not reflect the art world. The art world, much like a work of art itself, is renowned for its shock-value, its ridiculousness and its fleetingness. Unfortunately, however, the art world is also riddled with elitism and a relentless desire to make more money, be that in an ethical way or not.

This is perhaps why Tokenism has been a problem in art for such a long time. Until just under a hundred years ago, it was considered acceptable and praiseworthy for an artist to travel to a developing country, produce Gauguin-esque fetishisms of ethnic minorities or people of colour, and label them ‘beautiful’, ‘wild’, and ‘savage’. In the 21st Century, this is, of course, unacceptable, and such an overt suggestion of superiority is rarely seen. Instead, this tokenism manifests itself in a more subtle, and perhaps even devious way. To illustrate my point, I will pose a simple question:

How many black artists can you name?

Or better, how many black artists can you name, other than Jean-Michel Basquiat?

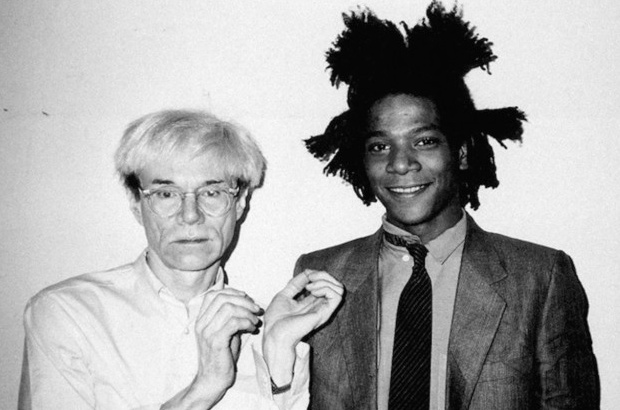

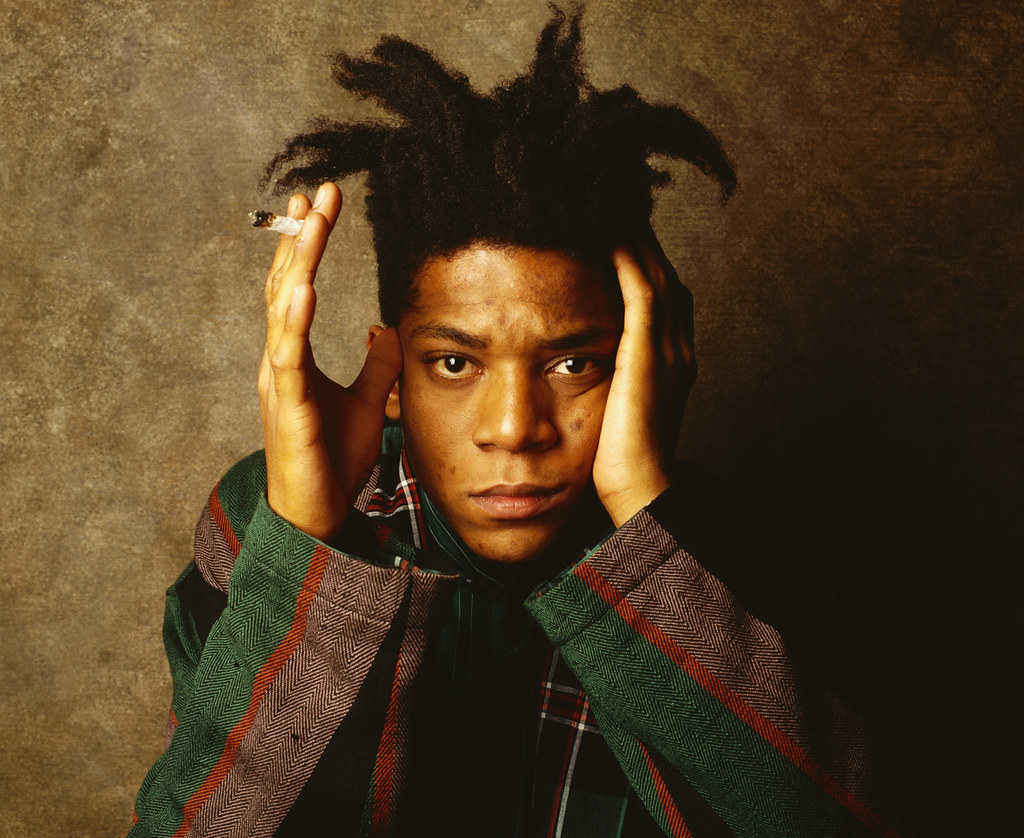

In contemporary popular culture, Jean-Michel Basquiat has become a powerful symbol of the artist-rebel. In his artistic prime, he was famous enough to have become a regular at the highly exclusive Manhattan nightclub Studio 54 and was part of the most elite celebrity circles which included the likes of Madonna and Andy Warhol. After his tragic death, with the artist overdosing at just 27 years old, he was catapulted into even larger fame, achieving numerous solo exhibitions and retrospectives at prestigious art institutions. Today, Basquiat’s artworks have produced some of the most significant sales in art history. Notably, his Untitled from 1982, which sold for $110.5 million in 2017: the highest sum ever paid at an auction for a US artwork.

Basquiat gained fame through several different paths: his talent, his uniqueness, his connections, but most importantly, his inability to be ignored. Starting off as a graffiti-artist, Basquiat left his traces all over Manhattan, signing off his signature scribbles under the name “SAMO”. He was mysterious, he was original, and many celebrities – white celebrities – loved him. And he was different. He was half Haitian, half Puerto Rican, and much unlike the artists people had seen before, both in the way his work looked and the way he looked. The art world could not ignore him.

As an art history student and someone who has grown up within the multicultural and ethnically diverse city of London, I would like to admit to feeling truly ashamed by the lack of black artists I can name. Though the number is not none, I could probably count the full sum on my fingers. Concerned, I asked my friends who are also art enthusiasts the same questions. Their answers were embarrassingly similar to mine. But why is this the case?

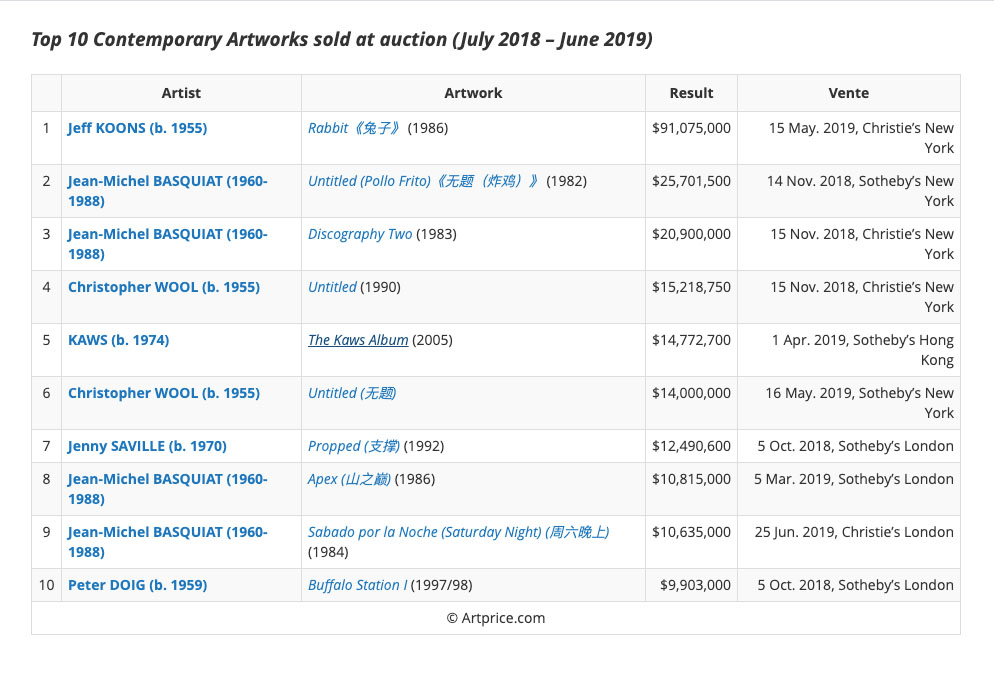

As it turns out, the art world’s scope of black artists is also fairly similar to mine. Between 2017-18, pieces by Basquiat accounted for 4 of the top 10 contemporary artworks sold at auction. None of the rest of the works were made by black artists. For comparison, Kerry James Marshall, 2019’s second highest grossing black artist, came 26th in annual turnover, with his highest sale being less than a fifth of Basquiat’s.

If Basquiat can sell for more than Rothko, Pollock, Warhol, and Calder, why can no other black artists come close to achieving the same? Why do they not receive huge annual retrospectives and have reproductions of their works all over posters, clothing, and furniture?

I am by no means trying to discredit the work of Basquiat, which I believe is genuinely ground-breaking. However, for the elite and predominantly white art world, Basquiat represents a gem. His is a perfectly romanticised story of the artist who came from nothing and made his way to the top of the art industry, despite being black. He achieved monumental fame, and tragically died from a drug overdose before reaching 30, leaving so much unfulfilled potential. He has become a symbol of their forward-thinking, their romantic token of diversity, their ‘token black friend’.

Though I paint a rather bleak picture of the industry I myself hope to go into, it is not all bad. Art institutions have in recent years made meaningful strides to increase inclusivity and celebrate the work of black artists. Galleries such as Tate and the Museum of Modern Art have pioneered the work of black artists, and were set to exhibit the works of several black artists in solo exhibitions in 2020 as well as exhibiting them alongside artists of different races.

But, in light of aiming for long-lasting social change in tackling racism and injustices against black people, we must ensure that these black artists are not treated as a trend; they must not simply be used by institutions or exploited by dealers to make more money while they are still ‘in vogue’. Art institutions must do better. Art historians must do better. We, as those who attempt to interpret, understand, and write the stories of artists and their work, must work to promote inclusivity and diversity in the art world. We must not lean on Basquiat to excuse our shortcomings. Most importantly, we must acknowledge that black artists are not a trend, and one black artist is not a symbol or token of the entire community.

Featured image: Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat photographed by Christopher Makos at The Factory at 860 Broadway in 1982. Image source: Sleek Magazine.