SOPHIE CUNDALL considers the wavering cinematic representation of polyamorous relationships.

The power of three, the holy trinity – or rather, unholy, as the case may be: the husband, the wife and the unholy unicorn (the term used for the third person in a polyamorous relationship). This is how film has fallen into portraying the poignant subject of polyamory. Under- (and perhaps more vitally, mis-representation) has been plaguing our screens both big and small exponentially over the last few years, in the guise of ‘indie’ progressive filmmaking. The world has experienced a wave of more progressive LGBTQ+ representation, but one piece of the jigsaw is still not quite complete: where is positive representation of polyamory? Two films come to mind as tentatively tackling the subject: Woody Allen’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona and Jérôme Bonnell’s À Trois on y Va.

Firstly, the return to heterosexual convention at the end of a significant number of the films tackling polyamory is a damaging and pervasive trope. À Trois on y Va is a delightful, quirky french tale where we follow a young lawyer who just happens to be having an affair with her two best friends individually, who just happen to be a couple. This, naturally, leads to some rather comic incidences, culminating in the classic scene of discovery, leading to a heady threesome as the protagonists discover the joys of the erotic element of polyamory (because, it is, after all, all about this element – just sex, not love).

A beautifully shot panorama of the three, laden with silk fabrics billowing and rippling in the sea air, running into the sunset over a beach, hints at a potentially ‘happy ending’ for this blossoming thruple. However, moments later, as one might expect, we are rewarded with a return to ‘normality’ in the shape of the Charlotte (the original girlfriend) gazing out of a car window with a voiceover explaining how Melodie and Micha will be better as a couple. This is a prime example of the tendency to thinly veil a close-minded, heterosexual agenda behind the tantalising suggestion of progressiveness. Though we are given an example of a functioning polyamorous set-up that is not simply to ‘spice up’ a couple’s sex life, catering to the monogamous sensibilities of a mainstream audience ultimately triumphs.

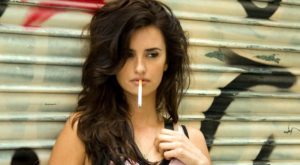

We are confronted again with this in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, a standard member of the Woody Allen canon that I have a somewhat fraught relationship with. Despite being an aesthetically beautiful piece of cinematography, the film is weighed down by the catalogue of tropes from which it cherrypicks so overzealously. The key flaw for me in this exploration of polyamory is the shameless exploitation of said tropes, creating a narrative that is highly misrepresentative of real-life polyamorous people and thus damaging. It is fundamentally flawed to correlate the unicorn with either a naive, doe-eyed blonde attempting to find herself in an overly glamourised version of La Vie Bohème in Spain, or the threadbare trope of the mentally unstable ex-wife who smokes a lot and is never seen without thick black kohl lining her bloodshot eyes. As much as these characters can exist, their concentration within one narrative is clumsy and problematic.

This also reinforces the representation of the unicorn as uniquely female, often a highly ‘damaged’ female, namely Maria Elenà, who is seemingly unable to function without her husband. As this is told through Allen’s male gaze, the crazy ex-girlfriend trope becomes all the more problematic. This representation of the unicorn as a destructive, tumultuous force initially attacking Cristina and Javier’s relatively functional heterosexual relationship is highly frustrating. Vicky’s return to marriage after an exploration of a relationship with Juan, and Cristina’s flustered escape from a relationship that then implodes without her then epitomises this convention of the return heterosexual safety; polyamory is dangerous and ‘just a phase’.

The geographical displacement that sparks our characters’ forays into the polyamorous sphere is an additional nail in the coffin of sub-par cinematic polyamorous representation. In Vicky Cristina Barcelona, the city itself becomes a character through titular placement on the level of the two physical female bodies who drive the plot towards its questionable denouement. In order for Cristina to dip her toes into the ocean of her sexuality, she must first be removed from her usual surroundings: a comfortable middle class subsection of American society in which the concept of polyamory is highly stigmatised and frowned upon. Thus, our naive heroine heads over to the symbol of self-exploratory debauchery: Continental Europe. If the film didn’t end with the breakdown of a potentially successful polyamorous venture with a return to ‘normal’ American society, it might be a progressive piece of filmmaking. Instead, it perpetrates the stigma through the portrayal of polyamory as a hedonistic ‘phase’ on a wild trip abroad which cannot translate into the ‘real world’. Polyamory, to Allen, is merely a holiday from inevitable conventionality.

Displacement and geography is also explored through the use of space in À Trois on y Va; the urgent necessity to leave the house that symbolises heteronormative domesticity surfaces moments after the protagonists’ first threesome. The next morning they rush off – this need for disassociation from mainstream society emphasised by their lateness – to a wedding, after which they are found romping on the beach. One has a real sense of a functional and whimsical relationship here, miles away from any man-made landscapes that could prevent their polyamorous bliss. Moments later, though, a car returns to transport Charlotte (and the audience) back to the comforting ‘reality’ to which Cristina is also transported, where polyamory cannot threaten monogamous societal norms.

These two representations of polyamory through the eyes of two male directors come burdened with woeful misrepresentation that, at times, borders on grotesque fetishisation. We are teased with a glimmer of hope for a functional polyamorous relationship that is productive and healthy, but are delivered back to comforting mainstream societal conventions in time for tea. Perhaps, one day, the polyamorous community will finally see itself represented as something other than a doe-eyed manic pixie dream girl crashing into an established couples’ bedroom one drunken night.

Featured image still from Vicky Cristina Barcelona; courtesy of imdb.com