MAYA WILSON AUTZEN interrogates the aetiology of the fallen woman.

The Book of Genesis provides not only the origin story of the Christian world but also a foundation for numerous literary works throughout history. From Eve’s transgression in Genesis emerged the condemned figure of the ‘fallen woman’, a character type which has pervaded literature ever since. Chapter two of Genesis presents God’s creation of the Garden of Eden, but by the third chapter, we witness Adam and Eve’s ejection from this paradise. Seduced by the legged serpent, Eve eats the forbidden fruit– thus sparking centuries of literature representing and reimagining a prelapsarian world and subsequent fall. Whilst the language of the Bible is mostly implicit, it seems unequivocal that Eve is to blame for the transgression. This idea is echoed in Milton’s Paradise Lost, where she is explicitly blamed for the fall of mankind. Milton’s satanic snake persuades Eve that the fruit is ‘pleasant to the eyes’, and ‘desirable to make one wise.’ The adjectives ‘pleasant’ and ‘desirable’ seem sensually loaded; this forbidden knowledge which Eve acquires has come to be synonymous with transgression and experience, typically of a sexually deviant kind. When God discovers man’s treachery, he turns to Eve and asks, ‘What is this you have done?’ If Eve’s crime is succumbing to temptation and gaining forbidden knowledge, and God is her judge, then her punishment is eternal submission to man:

In pain you shall bring forth children;

Your desire shall be for your husband,

And he shall rule over you.

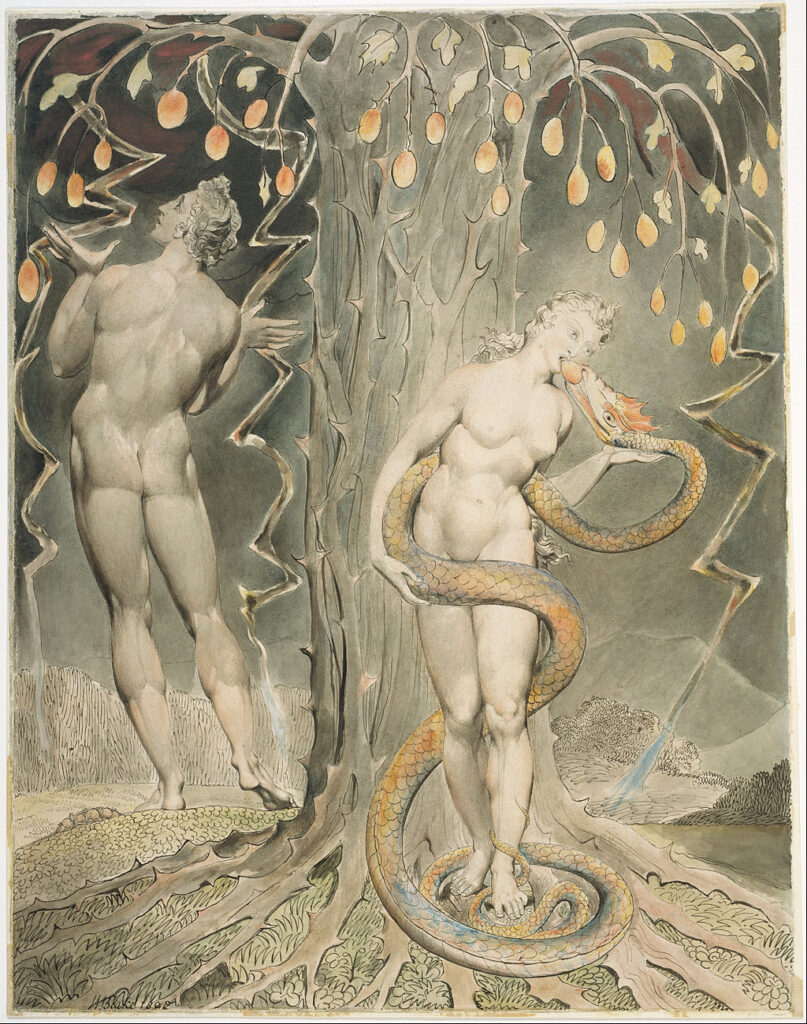

Eve’s damning sentence is echoed in the treatment of women throughout literature and history, and this transgression has since been translated into a sexual fall. In art, as well as in literature, Eve is portrayed as a figure of sexuality and sin by aligning her with the serpent. The Tree of Death and Life is an illustration from a 15th-century prayer book, depicting Mary and Eve as the antithesis of each other, with Eve naked and taking fruit from the mouth of the serpent. In Hendrick Goltzius’ painting The Fall of Man, Eve actively seduces Adam into rebelling against God’s wishes, and in Hans Balding Grien’s Eve, the Serpent and Death, she is presented as joyfully watching the serpent attack Adam. Eve and Mary are repeatedly employed as a binary for the presentation of women; in Paolo di Giovanni Fei’s Madonna and the Child Enthroned, Mary holds the baby Jesus on her lap, whilst Eve lies underneath next to a serpent. The caption reads: ‘the first woman brought death and sin into the world, but her counterpart Mary brings life and salvation for all.’ Mary and Eve are pitted against each other as the virginal ideal versus the sexually transgressed fallen woman.

From St. Augustine to Emilia Lanier, writers and artists since the Middle Ages meditated on Eve’s role in the fall, but it was Milton who gave interiority to the character of Eve. In 1667, Milton took the Genesis story and turned it into an epic tale of obedience, power, tyranny and rebellion. Paradise Lost presents a heavily politicised and gendered exploration of ‘man’s first disobedience’, which seems to place the blame more expressly on the figure of Eve than previous explorations. The Biblical serpent becomes the figure of Satan, and the image of Eve is deeply sensualised, as her hair is depicted as ‘Dishevell’d…in wanton ringlets.’ Even though she is coy and submissive, her hair suggests she is problematic: Eve’s ‘wanton ringlets’ parallel the coils of the serpent, and as in much of the art world, she is distinctly aligned with the snake. This epic poem engages with obedience, politics and sex, and the figure of Eve comes to represent a gendered version of the fall. For Milton, Eve is more susceptible to Satan because she is intellectually inferior to Adam. Milton says it is ‘too easy’ for Satan to whisper in her ear; does this mean she is more vulnerable because of an intellectual inferiority, or because she is ambitious and rebellious? In comparison to Adam, Eve has a greater desire for autonomy, freedom and knowledge, and perhaps this is the ‘fatal flaw’ which leads to her downfall. Once she has succumbed to temptation and eaten the fruit, she persuades Adam to do the same, who is ‘fondly overcome with female charm.’ Clearly, she has acted upon Adam, rather than the choice being purely his; her crime is more insidious and perverse because she has corrupted man. Ultimately, Genesis sparks a conversation continued by Milton– one that revolves around women’s capacity to tempt and be tempted, and thus the figure of Eve lives on in reincarnations of the female fall throughout literature.

The Victorian era saw an intense preoccupation with the fallen woman in literature, and likely owes its prevalence to the conservative ideology of the 19th-Century. Gaskell, Rosetti, Dickens, Tennyson and Brontë all negotiate fallen female sexuality and subversive femininity. Bram Stoker’s Dracula sees the inevitable fall of Lucy, whose vanity and desire to marry all three of her suitors (as opposed to choosing one) is classed as sexual transgression and foreshadows her eventual death. Christina Rossetti explicitly explores the punishment of the first woman in her poem, Eve, which laments the eternal retribution paid by women for Eve’s plucking ‘the bitterest fruit’.

Two Victorian authors in particular despair of the plight of the fallen woman: George Eliot and Thomas Hardy. They both engage with Milton’s exploration of the fall, and the gendered connotations of temptation and transgression, perhaps to expose the misogyny surrounding female sexuality. Hardy prefaces Tess of the d’Urbervilles with this potent, loaded idea of innocence and the loss of it through his subtitle, A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented. Tess of the D’Urbervilles presents the tragic tale of Tess Durbeyfield, a young girl who is elevated to high society because of a distant family link. She meets Alec D’Urberville, the antagonist of the novel and a character that can be aligned with the serpent from the Bible and Satan from Paradise Lost. Their encounter and his subsequent sexual violation of her is the root of Tess’ downfall. Critics have long debated Tess’ complicity in the so-called ‘rape seduction’ scene, despite her obvious lack of consciousness. Either way, this sexual transgression leads to Tess’ fall from grace, ultimately triggering the tragic sequence of events which follow. The title of the volume following her sexual aberration is entitled A Maiden No More, encapsulating the fact that she has been rendered impure through sex.

George Eliot also presents the tales of fallen women in her novels The Mill on the Floss and Adam Bede. Critics have compared Hetty’s transgressions in Adam Bede to that of Milton’s Eve due to their sexual nature; this is particularly prominent in Eliot’s depiction of Hetty gathering apples, in what can only be a deliberate allusion toEden’s forbidden fruit. The Mill on the Floss ultimately ends with protagonist Maggie Tulliver’s demise, closing with a Biblical flood that is reminiscent of God’s punishing humanity in the Old Testament. It is a perverse but fitting end for Maggie, who has digressed by eloping with a man her family did not approve of. The Miltonic resonances in Eliot’s texts in particular seem contradictory to her feminist writings, as Paradise Lost presents an underlying narrative of misogyny. Perhaps writers such as Eliot and Hardy use the themes explored in Milton’s epic to interrogate contemporary issues of female submission and sexuality.

And thus, the plight of woman and the strict sexual codes she has had to live by has been perpetuated by certain Biblical passages, and those who use it as a vehicle for female submission. The figure of Eve is echoed and replicated countless times over, reflected in the women portrayed as temptresses, seducers, harlots or whores. It is reflected in the portrayals of witches and prostitutes, the women abused and blamed, and the women reduced to mothers and wives. Readings of the original Eve have been translated and twisted into a figure of sin and fallen sexuality, thus commencing the enduring and aggregate trial of Eve, from which women have still not been acquitted.

Featured image source: nga.gov