ISABELLE BUCKLOW reviews ‘The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined’ at the Barbican.

Vulgar. When spoken aloud the word embodies a gross physicality that entails a snarl of the lips and a gagging emphasis on the second syllable. The vulgar itself is not a sensibility but a (usually snobbish) insult – used to denote not only the ugly, but the offensive.

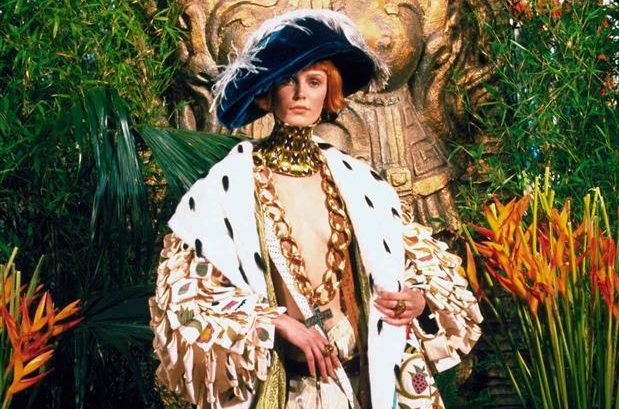

Exhibition curators Judith Clark and Adam Phillips argue that taste is not a simple binary of good versus bad. The outlandish garments on display in ‘The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined’ could be interpreted as iconic. Many of the outfits serve as metonyms for a time of transition. The attribution of this ‘vulgar’ status is not due to the clothing itself, but society’s response to it. This exhibition presents examples of fashions from the Renaissance to the present-day that have transgressed boundaries and challenged preconceived notions of taste.

The exhibition begins by breaking down the etymology of the term from the Latin vulgaris: ‘of or pertaining to the common people’. What follows are eleven sub-sections organised around themes that can be applied to the vulgar.

One category of the vulgar is the ‘classic copy’. Imitation and mimesis have their roots in Platonism, where they negatively connote a lack of originality. A copy is often considered a lesser version of its original. In the exhibition, this feeds into an exploration on the devaluation of the high end by the high street that has been provoked by our commercial opportunism. However, the curators provide balance—they do not praise or invalidate the copy, and suggest that terminology is never clear-cut. In an alternate Aristotelian light, imitation could be seen as essential for the acquisition of knowledge.

What is so fascinating about this exhibition is its philosophical framework. This is not your classic Tate-style retrospective but an eclectic array of highly pertinent illustrations of a complex and comprehensive theory. The curatorial power-couple even grapple with the ultimate dilemma—the mind/body problem. Clark, a psychoanalyst, studies the invisible realm of the mind; meanwhile, Philips, a practitioner and educator at the London College of Fashion, works within the realm of the visible body. These two phenomena, torn apart by Rene Descartes, are yoked together through clothes.

The right to judge what is vulgar comes down to taste: an immensely loaded category. He (or she, but to be honest, it is usually a he) who adjudicates taste is often in allegiance with the hegemonic order. Taste therefore creates a different kind of elite; taste divides. This is explored in the exhibition’s ‘The Ruling In and Ruling Out’ section, which charts the legal boundaries (dictated by sumptuary laws) of dress associated with social standing. Carine Roitfeld (ex-editor of Vogue Paris) famously said ‘you are either vogue or you are not vogue’. This brilliant but essentially meaningless soundbite reveals nothing, yet its violent classificatory juxtaposition exposes our inherent anxiety to belong. Clark illustrates this with accessories and garments clad in interlocking C’s and entwined D&G’s – prestigious totems of this modern clan-mentality.

The exhibition also playfully exposes prejudices within the gallery environment. The section entitled ‘Impossible Ambitions’ compares the act of an outsider wearing a military insignia to which they are not entitled to fashion’s ambition (with its rich materials and artistry) to be valued for more than just commercialism. This is not an exhibition of art; and the very choice of subject matter places it at a lower rank, for fashion is often devalued and considered anti-intellectual or frivolous. However, this exhibition seeks to elevate the status of dress by simultaneously presenting that which mocks such a status.

The exhibition could not have come at a better time. I visited the exhibition within the week of the Women’s March and that fantastically revolutionary spirit felt visceral in the context of this exhibition: set within an institutional framework, the exhibition is like the ultimate occupational rally-call. Fashion is also in the midst of transition; the sub-culture of vulgarity has triumphed. With bleach blond hair, a fake tan and a flashy gold tower, kitsch fakery has risen and punctured the comfortable sphere of the fashion elite. Phillips speaks of good taste’s capacity to protect and shield. It can be a kind of uniform that comfortably places you in the conforming crowd. By contrast, the vulgar is that which subverts a culture’s or period’s hegemonic ideal. This exhibition exposes that good taste is not always good; and that its uniformity can mask the sinister.

Clark and Phillips have moved fashion into the museum, creating a show that exposes the silencing of fashion and gives clothes back their agency. This exhibition is the most enjoyable philosophy of aesthetics class you will ever take.

‘The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined’ is open to the public and the Barbican Art Gallery until the 5th of February.