SOPHIA COMPTON explores the career of the late, great William Onyeabor.

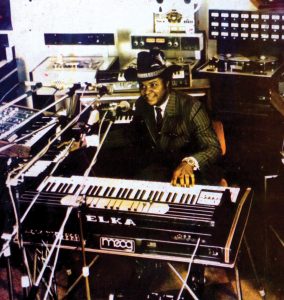

On the cover of one of Onyeabor’s records, ‘Atomic Bomb’ is emblazoned in an orange zigzag; another presents the posing musician beside the words ‘Great Lover’. So far, so bombastic – even for the late 1970s. But these dynamic titles stand at odds with Oneyabor’s inscrutable facial expression; his trademark half-smile. On both album covers the man himself is partially submerged, concealed by eight microphones in one and drowned in semi-darkness in the other. The concealed figures pose the question: ‘Who (on earth) was William Onyeabor?’ Despite endless attempts by record labels, music journalists and film-makers to find out, Onyeabor has successfully remained an enigma. Following his death last month, it seems unlikely that questions of identity and reputation will ever be answered.

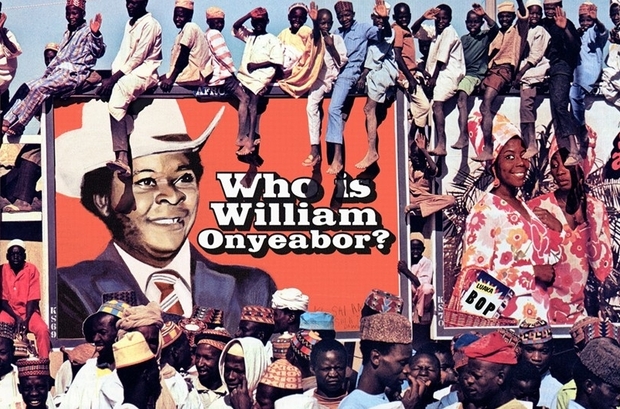

Onyeabor remains compelling primarily because of the music he made. Unlike anything else being produced in Nigeria at the time, throughout the 1970s and 80s Onyeabor created and released synth-based loops with an undeniably electronic sound. He was hugely popular in West Africa, yet remained relatively unknown elsewhere. This remained the case until ‘Better Change Your Mind’ was featured on Luaka Bop’s Nigeria 70 in 2001, prompting a quest for the artist that culminated in the re-release of his music in 2013 under the title ‘Who is William Onyeabor?’

As the title implies, investigations into Onyeabor’s life and artistry have spawned more questions than answers: how did he develop such a fiercely original and prophetically modern style? How did Oneyeabor come to record on such state-of-the-art equipment (including a range of synthesisers and his own vinyl press)? Was he financed by Russian Communists? Did he have a degree from Oxford? Did he have a backing singer who was incarcerated? Most pressingly, as Eric Welles-Nyström put it to The Guardian in 2013, how, in this day and age, ‘could someone have done all these things and there be no information available?’

In later years Onyeabor became a born-again Christian. Speaking to Welles-Nyström from his enormous ‘Palace’, with the words ‘Ezechukwu (or King-God) Palace’ inscribed across its entrance, Onyeabor said ‘I only want to speak about God. I don’t want to go back to that time’, before abruptly hanging up. Even at the height of his fame in Nigeria, Onyeabor was, as claimed by his former studio manager, ‘a guy you cannot approach anyhow’. His reputation exists as a confusing mix of self-abasement and occasional intimations of a voracious ego. He claimed he was disinterested in the idea of his music being revered or successful yet as Dorian Lynskey puts it, ‘his records were confident, expansive and frequently political, as if he were addressing fans across the world’.

The crux of Onyeabor’s contemporary appeal seems to lie in his shyness and self-fashioned reluctance for fame: because rumours about him were neither proved nor disproved, they multiplied. When he didn’t respond to Luaka Bop’s telephone calls, they sent a whole film crew to his hometown to investigate. He refused to tour or promote himself, prompting some of the world’s most respected artists (notably David Byrne and Damian Albarn) to create a ‘supergroup’ solely dedicated to playing his music. However, his continued inscrutability only seemed to fuel persistent and invasive efforts to unravel his story. Onyeabor clearly wanted to leave his past behind him and may have had legitimate private reasons for this. It was, it seems, often too easy to forget that beneath the veneer of compelling artistry and cultish following there lay a human being.

The story of William Onyeabor gives a fascinating insight into our association between music and the internet. Perhaps, unknowingly, Onyeabor utilised an attractive breathing space lying outside of an epidemic culture of over-sharing. Rejecting the music industry made him an attractive alternative to the distinctly ‘modern’ state-of-affairs whereby success is achieved via paying for likes, shares or views. Most contemporary releases now come with a video, interviews, a Wikipedia entry on the artist, a twitter profile, and other ever-increasing media. Onyeabor released provocative, political, enigmatic and engaging songs, never commenting on them or even encouraging people to listen to them.

Onyeabor’s rediscovered fame is, of course, down to the songs themselves, with their Afro-Beat motion and electronic lyricism. But his reputation is also testament to the fact that humans are enduringly attracted to the unexplained and enigmatic. The impenetrability of his story seems to resonate with a subconscious craving for mystery, a hunger for art forms to intrigue, not to sanitize, our imaginations. An unobtainable backstory can enrich our experience of the music itself: an artist with mystique demands our imagination do the work of filling the gaps in our interpretation of their art. Instead of consuming a pre-packaged product, listeners must engage and connect with sounds that are delivered with little context. The brain is coerced into dreaming up its own personal version of the truth, embroidered with its own idiosyncratic patterns. This is the magic of music. It is a relief to know that this inexplicable quality still holds us, and, that despite a worldwide proliferation of data, Onyeabor still remains a glorious enigma.