FARIDA EL KAFRAWY discusses the series of shorts Women at War at Underwire Film Festival

Women at War, a series of short films screened as part of the Underwire Film Festival, showcases the works of women directors and the war they wage against racism, environmental damage, the politicisation their communities and the female body, through their art.

When the curtains are drawn we are faced with a black background which shifts continuously. There’s a restlessness throughout many of the short films, but I Don’t Protest, I Just Dance in My Shadow, with its shifting shapes and constant staccato movement, crafted through stop-motion techniques, is the most visually agitated. As a depiction of the experience of Black female visual artists and animators in their fight for representation in the predominantly white, male creative industry, it is fitting that the shapes and music feel uncomfortable at points. With music chiming in the background, we hear the stories of the women interviewed. There is not a second of peace afforded the viewers, not a moment of stillness or silence; this reflects the continuous, exhausting struggle of young Black creatives in their professional lives.

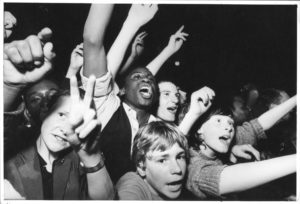

By far the overriding secondary theme in the series is immigration, with National Anthem, Only My Voice, Towards the Sun and White Riot: London exploring the politicisation of immigrants and refugees, and their struggle to be recognised and accepted in the United Kingdom, Europe and America. National Anthem is visually stunning, a satirical piece imagining a new brutal citizenship test. Under the impression that Tulsi, a young Indian woman, is going to begin working as a carer for an elderly English woman, we soon learn that her ‘test’ is to kill and eat her elderly dependent. Filled with dark humour and irony, this piece lays bare the dangers of the ‘us vs them’ mentality is. In a more journalistic style, White Riot: London explores the backlash and strong racism unleashed in 1977 following the rise in immigration. Drawing comparisons to the current political climate — regarding Brexit and the presidency of Donald Trump — director and editor, Rubika Shah, affirmed the film’s political aim. It is a successful attempt to revive the memory of the past so that we dare not forget it.

Only My Voice and Towards the Sun have striking similarities, the former following the lives of young adult female refugees and their new lives in Greece, far away from their families, and the latter following the lives of unaccompanied young children smuggled into America and awaiting confirmation of their residency status in a camp full of other Latino children. It is only through art that the young protagonist of Towards the Sun can tell her story, so traumatised that she refuses to speak — fear consumes her and others around her that she will be caught and kidnapped by smugglers. Only My Voice, however, is built on real interviews, though we never get to see any of the young women’s faces, as the politically precarious situation making it dangerous to reveal their identities. However, the shots of one young woman riding a bike, which she proudly states she also did back in Iran, as well as another young woman revealing that she has a boyfriend casually in conversation, breaks down stereotypes of Arab women as docile, timid and trapped in societal restraints. These refugees are free in their boldness and courage that is both so admirable and hard-acquired.

Tough, masterfully animated, further explores the experience of living outside one’s cultural homeland. Finally embracing her Chinese heritage after a long time spent ignoring it, a British-born daughter explores her mother’s past in China, whilst her mother expresses her regret at not instilling Chinese language and culture in her as a child. This was the most compelling film of the night; the unique animation style, snippets of the interview and music worked perfectly in sync to illustrate a profound family history.

The shortest of the films, Now You See It, envisages the destruction of our planet, calling us to action to preserve the natural environment. Now you see the rainforests, the beautiful stars in the sky and the mountains, but tomorrow it could all be gone — with tonnes of un-biodegradable plastic dumped into our environment, all we may see one day is a sea of old plastic toys. This theme of environmental activism is also central to Never Land, alongside the story of Noah’s Ark. Beautifully shot in a British coastal town, the film follows eleven-year-old Noah, who is obsessed with the idea that one day the world will flood completely. The sight of water dripping distresses him; he gets up in the middle of class to turn off the dripping tap properly, and at home protests when his father leaves the tap on to ‘prove’ that nothing will happen. Noah’s nightmare is realised when he wakes to the whole world underwater beneath the attic; it is only Katie, his neighbour, who survives with him. They sail on a bathtub trying to find the only place that survived the flood — Never Land. Both endearing and disconcerting, it confronts the horrific consequences of climate change in a subtle manner. Although this short film has been primarily screened in schools, it was certainly not solely made with a young audience in mind, and there is nuance – subtle, humorous and unsettling moments – that adults can appreciate.

Exploring the female body and its politicisation, Wrongheaded is the most stylized and abstract film of the night. Merging dance and spoken word, it is a response to the 8th Amendment of the Irish Constitution. Rather disturbing and difficult to interpret, it is a piece that requires deep attention, but one that on the surface successfully captures the turmoil Northern Irish women are still forced into today. With abortions being harshly restricted, the UK government has even recently announced its intention to provide Northern Irish women with free abortion services, so that they can maintain the same level of freedom. That Time of The Month similarly tackles a taboo issue, the period, by imagining a world in which instead of being a part of a women’s natural cycle, it is a part of men’s. In a light-hearted and hilarious manner, this short challenges the societal attitude that the female body cannot be discussed in public. If they were experienced by men, periods would be a cause for celebration — at the very least they would be unashamedly referred to and accepted as part of the male body.

Women at War formed of a selection powerfully thought-provoking short films, and is a testament to the strength of women and their unique creative visions. Their art is the weapon that we need to win the war for a world that is kinder and more just.

‘Women at War’ screened on the 23rd November at the Barbican cinema 3 as part of Underwire Film Festival. More information on the festival can be found here.

Featured image courtesy of underwirefestival.com