Second-year Architecture student KAI MCKIM decided to interrupt his studies this academic year and work on a project planning, designing, and constructing a sculptural studio in Oxfordshire. WILL FERREIRA DYKE speaks to him about the realities of working on a commissioned project, in comparison to a Bartlett brief.

Kai! I miss seeing you lurking outside the Bartlett. How do you feel interrupting your studies, do you think it was a much-needed break?

Partly yes, but I think I am missing it. The main reason I interrupted was because I thought that phasing back to face-to-face teaching would be a shambles. There was a lot of unpredictability and what I thought was hot air optimism for this year’s prospectus. But it seems like they’re doing a better job than expected. I miss having that vigorous routine, working together, seeing lots of people, and even commuting! That being said, I’m blessed to have this project, it’s keeping me very busy.

Can you discuss this project further?

I’m working on a commission for a client who wanted to build a sculpture studio-cum-office-cum-furniture storage space. Ultimately, it is a glorified shed and shipping container, but we’ve designed a courtyard and compost toilet to go with it. It’s a very chaotic process, and I’m fully entrenched in the reality of constructing this building every step of the way. I started with initial site surveys and then progressed into drawing up sketches. These were then followed by accurate plans, producing various iterations to reach a point where the client is happy to go forward. Then comes the practical, physical dimension of the project, clearing all the brambles, prepping the ground with compacted gravel and weed membranes. We will then need to excavate, hire a digger, hydraulic jack and all that sort of stuff, lay a lot of concrete foundation and then start building up from there.

How do the realities of building a structure compare to your expansively creative Bartlett projects?

It’s just so real! Granted this project is only small, but nonetheless extremely intricate. It is exactly this reality, using our hands to physically engage with a structure that will endure, that makes the project so exciting. This type of work comes with many constraints, however: fitting everything in the budget, the annoyance of a certain touchy neighbour, and keeping the client happy (which, in a way, can be compared to the approval of Bartlett tutors, but they’re not paying me!).

Going forward with this project, will you be doing all the construction – plastering, assembling – and all the other architectural verbs I have no clue about?

Yes, myself and my boyfriend, Nic are taking on all the jobs: designers, project managers, fabricators and now employers. Even down to the minutiae of paperwork; I’m having to send off invoices and pay suppliers. The project is estimated to be finished around late February/March. I want it done quickly to allow time to do other things this year. Though this will mean that we are going to have to work through winter.

Heat warmers, hot water bottles and brandy at the ready.

Oh yes brandy, of course the brandy.

Post completion, post brandy, what sort of things are you interested in seeing? Your second year project focused on sustainable technique, is that where your interests lie?

Yeah, I suppose so. I can remember in first year, there was a period where I nearly dropped out of university, partly because of the modules supposedly to do with sustainability. I remember being disheartened back then by the lack of initiative or even interest in seriously applying any degree of climate awareness to university projects by tutors or students. The construction industry contributes to approximately 40% of all CO2 emissions, mainly from concrete as well as embedded carbon. But this was almost seen as a given, at least in my opinion. Recently, there has been a push for more sustainable building globally with the changing zeitgeist of climate change awareness, which is getting me quite excited and making me think that my future in architecture will likely be in that field. There is so much innovation needed, which is at once both daunting and exhilarating.

What are your plans for third year, do you think this year will be useful for your next university project.

Yes, for sure. Working on the current sculptural studio project, even at its diddy little scale, is helping to conceptualise the reality of a future project, and will be so useful in understanding the feasibility of whatever I decide to create. Maybe this sculpture studio will head me down a more practical route. Who knows.

Who knows, only time will tell!

Indeed, early days.

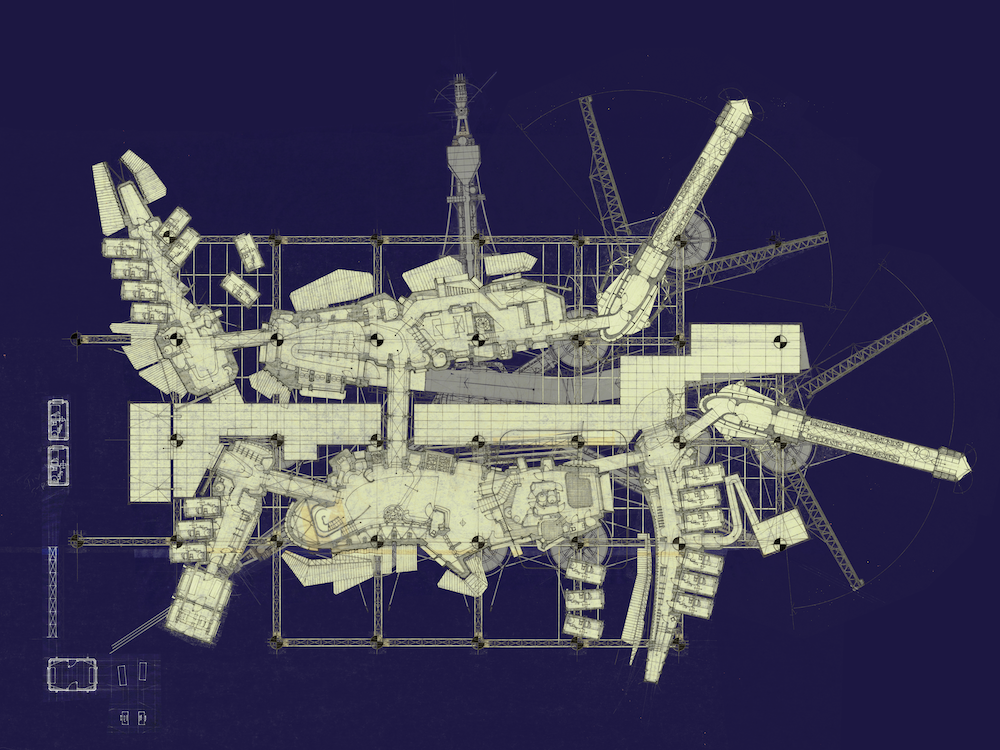

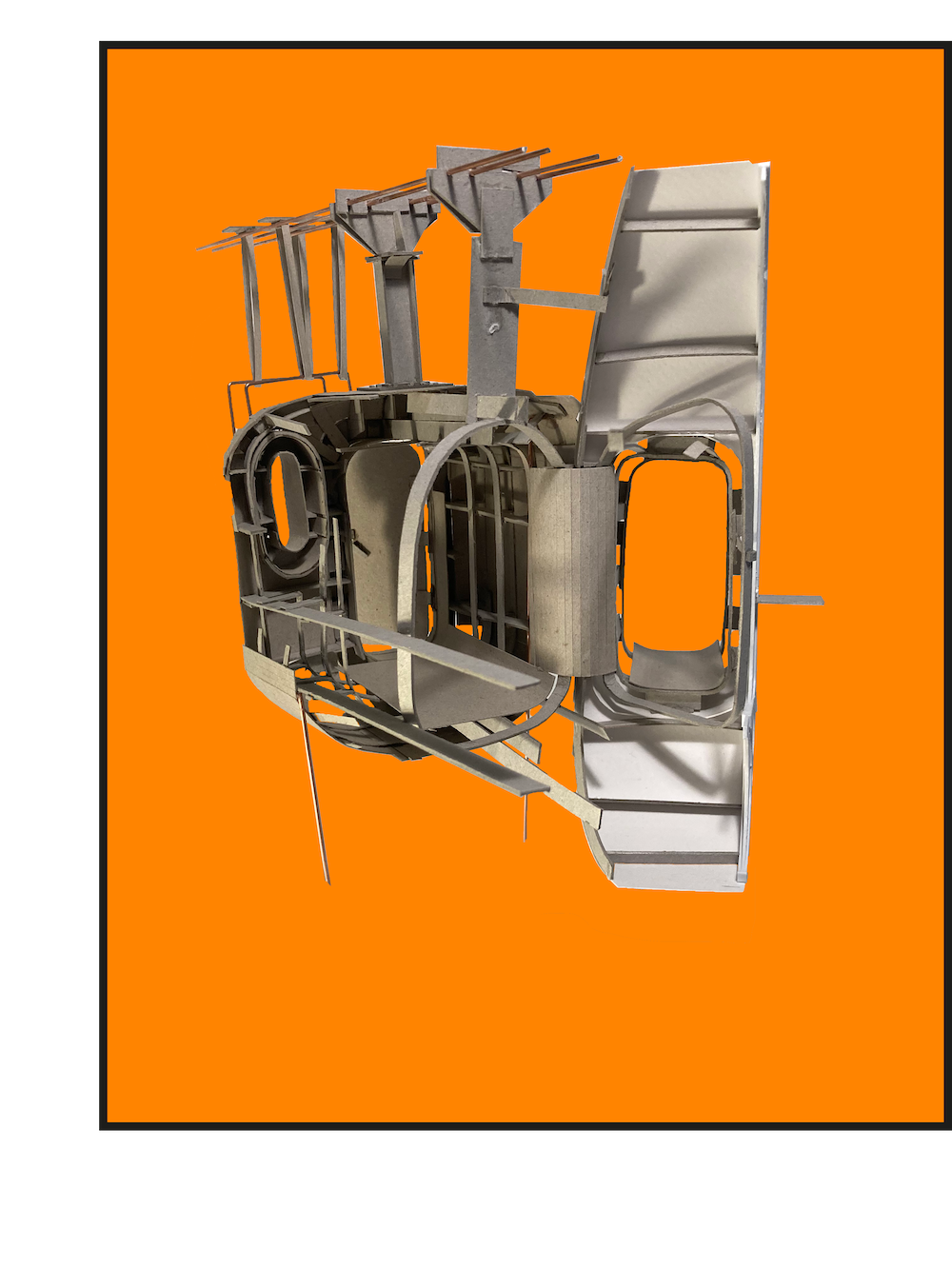

Can you talk further about your second-year project, Rasmussen’s Carcass? I’ve seen some of your renderings and they are simply beautiful.

Thank you. The project was titled Rasmussen’s Carcass following the brief set by my Unit 12 tutors, exploring the notion of ‘citadels’. It was actually a very pertinent title over the second lockdown: a period of isolation, stuck in your own personal citadel, a place of defence, the boundaries of the space well set and decided upon. I was looking at the variety of osmosis that occurs at these boundaries, and in what context particular typologies arise. That was the starting point which ended up directing the project in a decidedly machinating, mechanical direction.

So, what was the building you ended up designing? Lay it on me.

Oh god. It became a very complicated programme. I started looking into a community of 600 people in Greenland, a place called Qaanaaq in the northwest corner of the island. The town is situated at the mouth of a long fjord called Inglefield Bredning, where the inhabitants, an ethnic subgroup of Inuits, the Inughuit, are famed for their seclusion: they have very little contact with the rest of Greenland. Traditionally they were extremely isolated and lived in great harmony with nature. So, the project – well, it was such a ridiculous project in the end – was situated in this context.

What type of structure was it you ended up designing for the community?

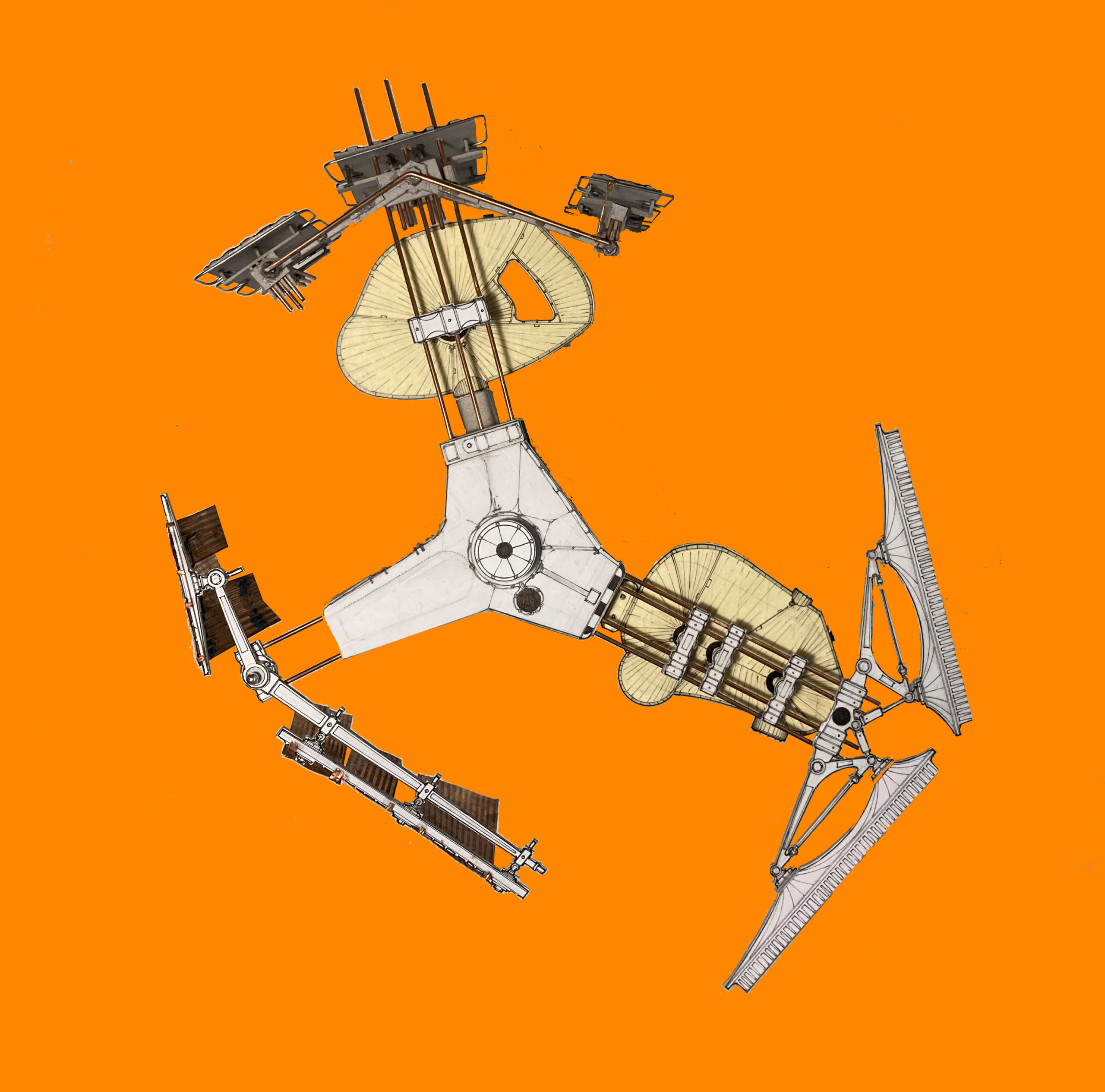

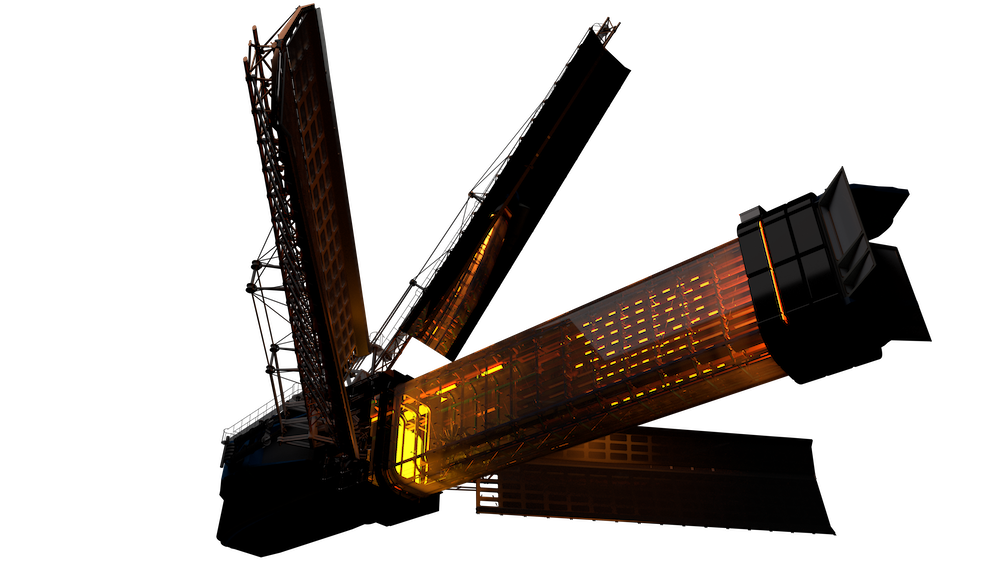

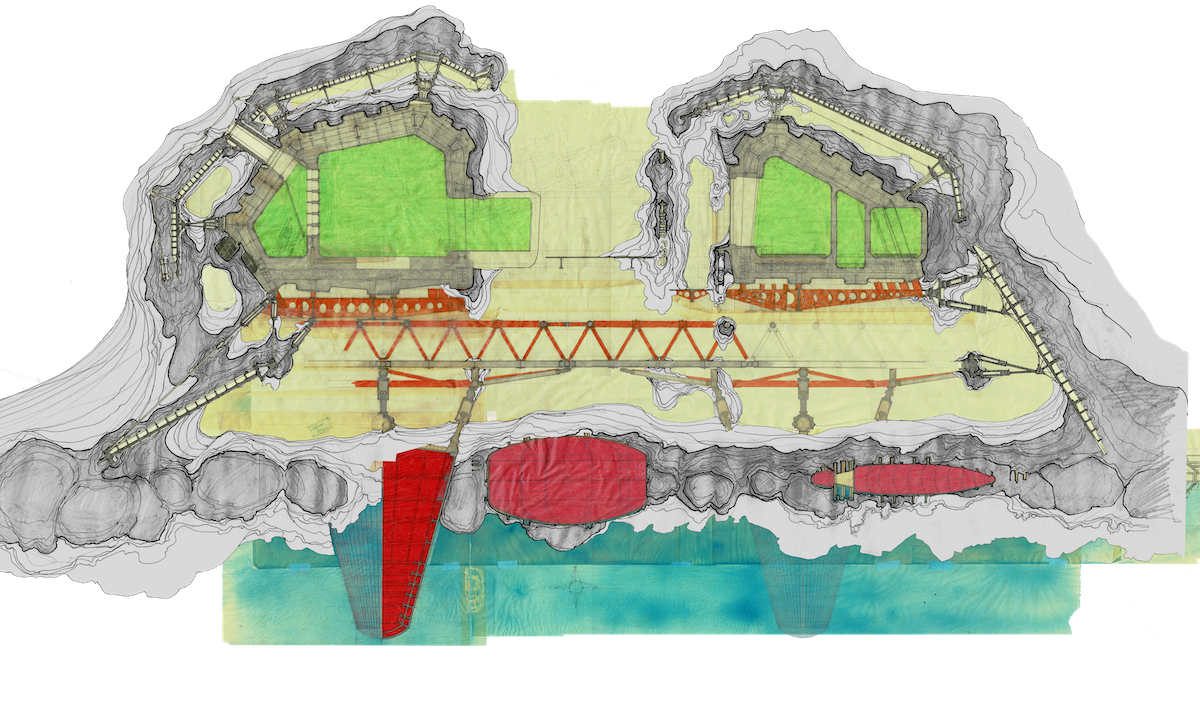

The station consists of various programmatic elements, pods that plug into the structural plane, elevated above sea level by cone shaped buoys and arrangements of pistons. It consisted of numerous elements aimed to provide the local community with an influx of wealth and tourism, as well as to alleviate its dependence on foriegn imports of food. I designed accommodation, recreational areas, and sustainable food facilities. The Inughuit’s original source of food was subsistence hunting, however, when forcibly modernised they lost much of the practises that formed their cultural identity. The project can be read as an attempt to aid the reconnect of the Qaanaaq community with their landscape and history: the Inughuits were a nomadic community who would seasonally move between various sites but, having been evicted from their main cultural settlement at Thule, were relocated to a modern built Danish town (the modern day owners of the island). Immediately imposed on them was a more sedentary way of life. Their cultural identity has thus declined, as well as their traditional hunting practises. I wanted to preserve this identity through my project.

The agricultural development consisted of these two big greenhouses. Because there are very few trees in Greenland, shown only by a very small line on google maps, traditional Inughuit Qarmaq’s used whale bones as supports, in combination with seal skins. I wanted to make my structure somewhat organic in reference, hence, many of the aspects of the proposal had a skeletal, rib like protrusions.

How was your project received, how was the feedback, what was your favourite part?

I did love the greenhouses. I got very deep into the aqua and hydroponic irrigation systems and so on. The biggest feedback throughout the year was that ‘you’re studying architecture, not engineering’. I think I finally reached a point where I was trying to cram so much incongruent stuff into a single building that it became a rather overbearing and decidedly confused task.

Finally, New project. Quick fire round.

Location?

Egypt

What type of building are you designing – don’t you say pyramid.

Maybe another sustainable agriculture farm.

With what material?

Maybe rammed earth, something massive and heavy. Although to be more protected from climate change you perhaps would want to be further north.

Okay I’m currently picturing the barbican conservatory, but in Egypt.

That would be unliveable, too hot. Imagine that in Egypt. You’ll be roasted alive, and won’t be going there for your Sunday coffee or brunch. There is a café there right?

I think you can get wine there too. I’ve definitely seen someone drinking wine there before.

Well that wine would evaporate.

So true, what would be the point of having wine in an Egyptian agricultural farm when you can go to the pub.

I can see very little really. Speaking of, let’s head … Pint?

Featured image courtesy of Kai McKim.

An extract from Will’s interview with Kai features in Era Journal’s Issue 14, ‘Get Real‘.