ALEK ROSE explores how politics and fashion have been linked in Russia since the revolution.

After being associated with social and criminal deviancy for the majority of its existence, the tracksuit has recently become a staple of international fashion weeks. Routinely hitting the catwalk for Gosha Rubchinskiy, the tracksuit is equally a regular feature of Supreme and Palace collections. This resurgence suggests that there has always been an underlying and enduring artistic value to the tracksuit. In an attempt to (maybe unnecessarily) intellectualise the tracksuit, I look to Russia – arguably the country most heavily associated with the the birth of the tracksuit – and also with Constructivism.

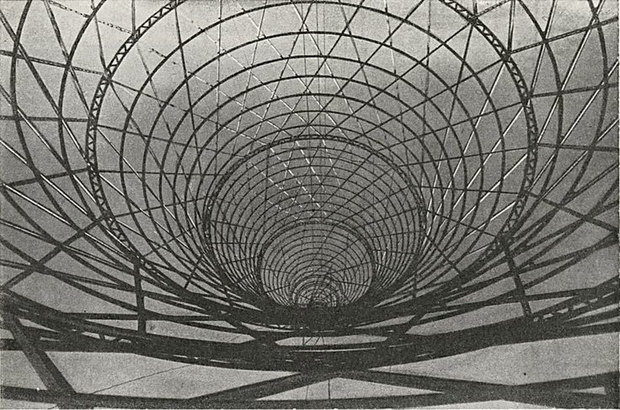

Constructivism is an artistic movement that originated in Russia in the early 20th century. The movement was dedicated to bringing art, which had previously been considered something only for the elite classes of society, to the ordinary people of the modern world. It evolved into something representative of everything that had just been overthrown by the revolution.

After the revolution, art began to be incorporated into science and technology in order to service the Soviet citizen. Vladimir Tatlin – a pioneer of constructivism – set to work in collaboration with engineers and scientists creating workwear and even an oven for communal living. Art without a purpose in everyday life was now considered worthless. Whilst this shift in value meant that many Russian artists relocated to Paris or to America in order to experiment more freely, other Russian artists creatively accommodated the change. For example, a famous Rodchenko design features a black and white portrait of Lilya Brik, Russian socialite and writer. Her figure set against a strikingly bright geometric backdrop shouting the word ‘Книги’ (meaning ‘books’), ultimately stressed the functional importance of reading for all members of Soviet society.

Similarly, the functional concept behind the tracksuit is closely related to the ideals of Constructivism. Designers such as Varvara Stepanova (1894-1958), and Nadezhda Lamanova (1861-1941) pioneered the Constructivist ethos through their creation of clothing. The new Soviet man and woman – healthy, hard-working, and beautifully androgynous – needed clothes in keeping with their lifestyles. Constructivist designers began to consider the human body less as a static shape on which to hang clothing, but rather a moving tool which ultimately required practical, simple clothing to increase the work rate and efficiency of the wearer.

The tracksuit undoubtedly follows these criteria: made of light, warm material, it has the express purpose of keeping an athlete warm before and after an event. The tracksuit’s adherence to Constructivist principles is evident in the early concepts resembling tracksuits that Constructivist designers developed. Anatoly Lunacharsky, the People’s Commissar for Enlightenment, even recognised спортодежда/sportodezhda, meaning ‘sports clothing’ as one of three categories of clothing in a 1928 article entitled ‘Cultural Revolution and Art’.

It would be sacrilegious to write an article about Russia and tracksuits without mentioning Gosha Rubchinskiy. Born in Moscow in 1984, Gosha Rubchinskiy experienced a formative period of modern Russian culture firsthand. The period beginning in the mid-’80s is referred to as ‘Гласность’ (‘Glasnost’), characterised by an increased transparency between the Soviet Union and the rest of the world. With this transparency came culture: related in particular to music and fashion. Having grown up during and been inspired by such a transient, exciting period in Eastern Europe, designers such as Gosha Rubchinskiy and Demna Gvasalia have risen to become two of the most venerated designers of the moment. For Gvasalia, it was his ironic use of branding that led the brand Vêtements to worldwide success. He has played around with logos such as that of DHL’s. For Balenciaga, he pushed political subjects through his alterations of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign logo.

Rubchinskiy, who tends to build on subjects from Russian culture for inspiration, has found a way to feed so-called ‘Post-Soviet fashion’ back to the West. His use of the exotic cyrillic alphabet caught the attention of Western audiences. Whether it spelt out the word ‘Спорт’ (Sport), or something with a political nuance, ‘Готов к труду и обороне’ (Ready for labour and defence: The name of a Soviet physical culture program). Time and again, he encapsulates what it is to be a young person in Russia. His art is a manifestation of the then-growing daily tensions between westernising 20th century forces exerted upon the Russian government, and by extension, the Russian people, and the ever-present, deeply-rooted traditions of the country. By pulling inspiration from the rich culture of the nation as partially embodied by Constructivism, and combining it with contemporary trends such as skate culture, he pays homage to a culture of making do with what you had around you when it came to fashion. We see this through the DIY-like feeling of his shows, with their mismatch of outfits: an old denim jacket and a pair of counterfeit Adidas tracksuit bottoms perhaps, à la ‘Squatting Slavs’.

In an age when buying clothes is quicker and easier than ever, when you can see outfit after outfit simply by scrolling down your Instagram feed, it is important to recognise the significance behind the clothing we’re looking at, and buying. Cultural intersections such as those that exist between fashion and politics have occurred and will continue to occur for as long as clothing is produced.

Featured image courtesy of pinterest.com.au.