BECKY KELLS investigates the increased marketisation of UCL, the National Student Survey, and calls to boycott it.

A quick glance at the National Student Survey (NSS) website does nothing to raise alarm bells. It markets itself both as a chance for soon-to-be alumni to anonymously evaluate their university experience – helpfully indicating areas which require improvement for specific institutions and departments – and as a statistical guide to student satisfaction for prospective undergraduates. It is ‘obligatory’ that all publicly funded universities provide the contact details of their final-year students to the NSS, but it is ‘voluntary’ for students to complete the survey. University departments can remind unresponsive students to partake, but they cannot make the survey a requirement, or influence student responses. Ultimately, the choice to complete the NSS rests with individual final-year students.

However, this year the choice between completing or ignoring the NSS has become more complex. The NSS has been adopted into the Government’s education reform scheme, Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF). Together with student drop out rates and employability, NSS overall scores will be used to hierarchically score universities, awarding them ‘bronze’, ‘silver’ or ‘gold’ status. Achievement of the higher accolades will enable institutions to increase tuition fees, on an annual rolling basis, by up to 3-4%.

The development is controversial for all involved. This is not the first time the survey has been instrumentalised in the creeping marketisation of tertiary education ongoing since the ’90s, nor the first time it has been boycotted: the competitive ranking of universities and departments that it results in, and consequent changes in funding, have led to (much smaller-scale) boycotts in the past. However, since its creation in 2005, the results of the Survey have never before been so directly used to justify fee increases, or to permit high-scoring institutions to charge more. That certain institutions will now have the option to increase fees – based not on ‘Teaching Excellence’, as implied by the NSS website, but in fact on the number of responses simply citing ‘student satisfaction’ – is unfair. While senior management teams can barely restrain their excitement at the prospect of raising fees further, individual departments are in a complex double-bind: they are bound to the NSS by university managements, by funding imperatives, and also as a source of feedback, but are largely opposed to its financial implications. For students, responding to the survey and expressing their opinions on their university experience, risks costs for future students.

Responses across UCL departments have been divided, and it has been left to the various unions to provide a clear message. UCLU has urged students to boycott the survey, in cohesion with the nationwide boycott organised by the National Union of Students. While both organisations emphasise how vital student feedback channels are, they condemn the transformation of the NSS into a tool for marketisation. The NUS states that the survey was ‘never intended to measure teaching excellence, or for it to be linked to funding and fees’. David Dahlborn of UCLU condemned the NSS, stating that ‘it will be used within the Teaching Excellence Framework as a means to justify further cuts’. The University College Union, which represents the staff members of UCL, also released a statement in opposition to the Survey’s association with the TEF.

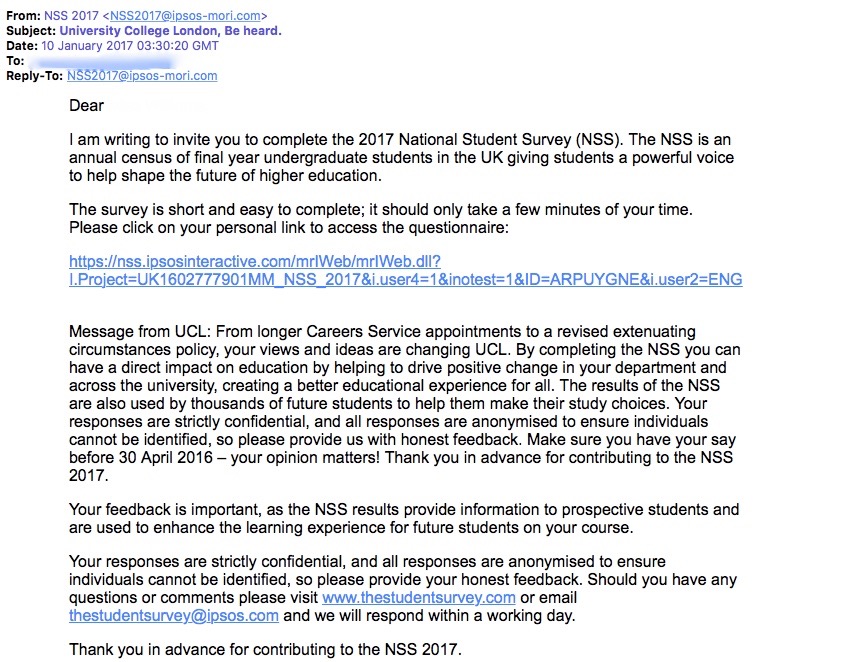

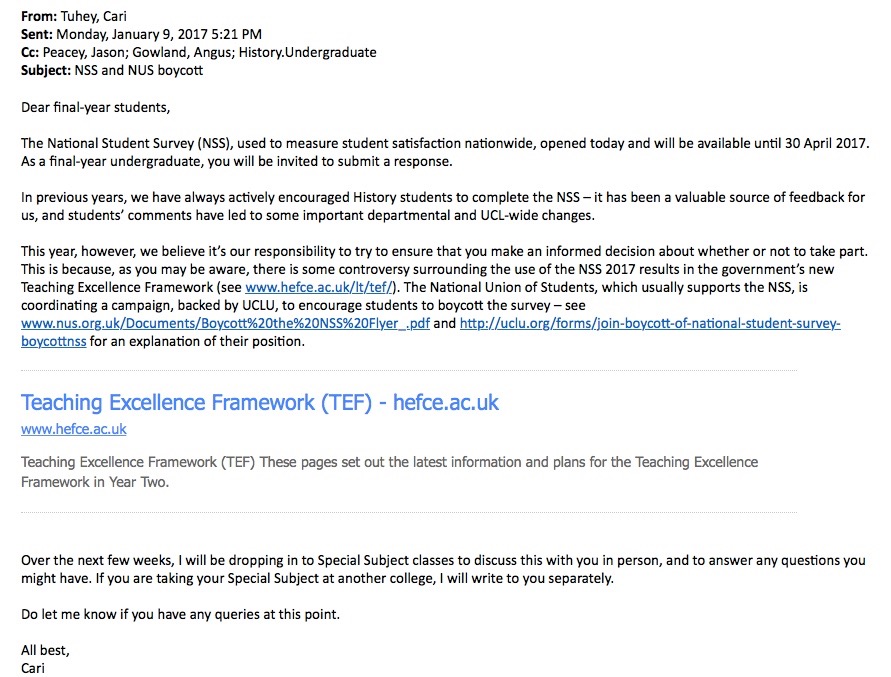

Meanwhile, final-year students have received the usual reminders about the NSS – some increasingly persistent – from their departments and from the NSS itself:

Despite the sheer quantity of persuasive emails being sent, there is still a misleading lack of transparency around the survey. In the FAQ sections on the NSS website, the academic benefits for institutions, prospective students and alumni are extolled alike, without a single mention of potential fee increases, or the Gold, Silver and Bronze ranking system. In providing a short overview of the NSS boycott and the controversy surrounding it, the UCL History department email does more to educate eligible final-year students than either the government or the NSS website:

Most students set to graduate this year were in their final years of school when fees were trebled in 2012, and halfway through university when the 2015 budget quietly and unceremoniously scrapped tuition grants – they are no strangers to increasing tutition fees. In linking the NSS to the TEF, the Tory government further condemns the university experience to marketisation, recasting education as a purchasable commodity rather than a human right, and forcing institutions into a destructively simplistic model of competition with each other. This affects not only students – who graduate from English universities with, on average, a debt of £44,000 – but also staff and their funding for research. Inevitably, this impacts on the quality of that research and the teaching available too. ‘A lot of departments are squeezed for cash’, David Dahlborn points out, ‘and it’s important to remember the reason why they are squeezed for cash is because of government and senior management cuts in the first place.’

The NSS could easily be cast as a well-meaning feedback resource, but this is soured by its association with unforgiving higher education policies. Its initial purpose, to mediate between undergraduates and their respective departments, could be all the justification final-year students need to fill out their responses. But the barely-disguised financial end goal casts the 27 questions themselves in a different light. They are unmistakeably designed to function like some sort of national focus group. One asks participants to select how far they agree or disagree with the statement ‘The course is intellectually stimulating’, another asks students to evaluate if their ‘communication skills have improved’. The ‘tickbox’ format of the survey does not provide a space for detailed elaborations on individual questions or specific issues departments and institutions face, with only a general longer evaluation at the end of the survey. The NSS states itself that ‘the data are not intended to address respondents’ requests at a personal, individual level.’ Yet it is these deliberately vague, all-inclusive questions, unlinked to actual change at universities, that are the determining factors for whether an institution qualifies for bronze, silver or gold status – and ultimately for a fee increase. There are so many aspects to the university experience which the survey does not, and cannot cover. Rather than allowing for institutions to develop their specific, often niche, strengths, the survey creates a standardised set of rules to which universities must adhere. A university experience centred around prompt feedback and good library resources is not everything, and certainly does not necessarily warrant an increase in fees, and yet this year’s NSS will make that so.

Boycotting the NSS does not mean that, as a final year student, your voice will not be heard. In fact, the NUS and UCLU alike have been quick to dispel this idea, both providing, or proposing the provision of, their own feedback services. Alongside these more general channels, departments themselves extend surveys – often on an annual basis – in which questions are exclusively tailored to specific degree programmes.

The changes to the NSS reflect the government’s ‘pick and choose’ attitude towards student opinions, making use of them where they fit their agenda, and saddling them with more debt in the process. The NSS marks education out as a privilege rather than a right, and it sends a message, loud and clear, to students from less financially stable backgrounds: this option is not for you. It creates another avenue for universities to exploit individual departments and their staff, subjecting them to funding cuts that are felt most acutely by the students, but also by the whole community. The demonstrations against tuition fee increases and education cuts have been amongst the most widely attended and documented in recent years, and to introduce further increases in fees under the pretence of listening to the opinions of the people who so vehemently oppose them is an act of hypocrisy.

The National Campaign Against Fees and Cuts provides more information here.