JADE BURROUGHES explores the noise of protest art by neo-conceptual artist Jenny Holzer.

In a 2017 survey, Spanish visual media artist Daniel G. Andújar claimed that ‘democracy has become an aesthetic matter’. He is not alone in this analysis. He is one of many to recognise art’s political potential. To me, Andújar’s mantra starkly resonates with the work of neo-conceptual artist Jenny Holzer. Since the 1980s feminist wave, Holzer has demonstrated an unrivalled capacity in tearing through dominant socio-political narratives which stifled critical democratic conversation and pacified populations. Noise is vital in intercepting these top-down induced unilateral discourses: one can think of no noisier art genre than protest art. Holzer stands as a frontline proponent of this. In the current political climate, silence is utilised as a weapon to repress the propagation of justice noted most overtly in the use of gag orders to silence #MeToo victims. It is necessary to analyse the works of artists such as Holzer, who is motivated by an impetus of social justice. She produces art that forces critical discussion about detrimental political environments.

Protest art demands to be heard. It gives voice to those silenced by dominant power structures. Historically, the rights revolutions of the 1960s-80s gave birth to a class of militant ‘guerrilla’ artists who used words in their artwork as weapons. They also established a dominant strand of aesthetic social resistance. Known for her text-based work, Holzer pertinently falls into this category of social activist artists. Along with this wave of artists, she made it her business to challenge widely accepted narratives. They generated open discussions and questioned important issues of gender, race, sexuality and war. Now this production of conversation still remains vital to manufacturing an open, democratic path to securing social justice.

Holzer’s work fits the eloquence of a politically conscious individual. From its inception, it has commented on controversial social issues. Her subject focus tackling battles in all their varying forms from women’s rights and AIDS awareness, to war-ridden Yugoslavia and Iraq. Her preference for heavy subjects is rooted in the hopes that ‘doing something could yield a happier result.’ Holzer’s words echo those of a true social activist; taking action to bolster causes she is passionate about.

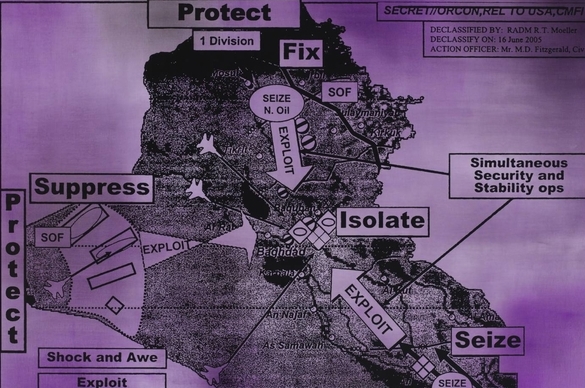

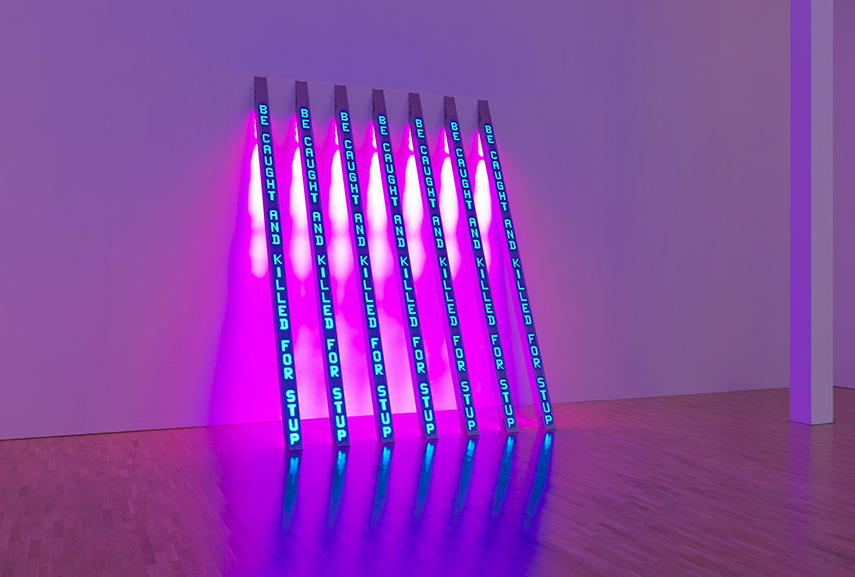

Holzer’s messages, medium and presentation are all politically charged. Her stark one-liners, such as ‘abuse of power comes as no surprise,’ bring attention to social injustice with a clear anti-authoritarian streak. Her war-orientated pieces, such as Protect, Protect (2007), and They Left Me (2018), starkly allude towards the toxic power relations currently existing within Western societal systems. After the tragedies of 9/11, she began utilising declassified government documents as primary source material. From descriptions of military abuses in Afghanistan, to interviews with former detainees in Syrian refugee camps, various documents were displayed with heavy black lines struck through information: they were deemed too socially sensitive for public revelation by government officials. These works expose the practice of censoring information to generate unilateral discourse which conceals injustice through induced silence.

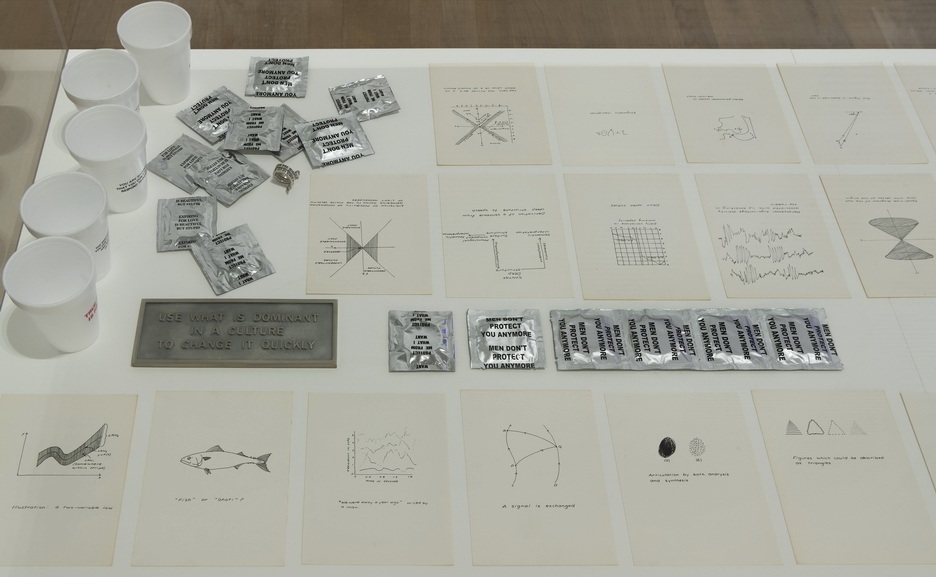

Holzer makes it her artistic mission to subvert the narrow channels of information we consume on a daily basis, which are conducive with political passivity. This has often been described as her ‘short circuiting the system.’ Through use of varied medium she replaces the impersonal and monotonous with the personal, politically sensitive and provocative – this is an especially consistent practice throughout her Truisms series. One piece involved replacing the impersonal patriarchal drones of advertising on condom wrappers, with emotionally probing messages about the trivialities of romantic love and motifs of toxic masculinity. The urgent messages inscribed, such as ‘men don’t protect you anymore’ resonate in the current political climate. The recent appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to Supreme Court, following accusations of sexual assault, brings the low priority assigned to female protection within the Republican political agenda into stark reality. Holzer’s protest art gives voice to this type of injustice. Evidently, her work remains in touch with America’s political landscape. It seeks to intercept the passive reception of information from damaging sources at every turn.

The democratising effects of her art are best seen in its medium. Holzer’s art manifests itself in a dual capacity as both public art display and a form of social intervention. She justifies her use of words by claiming ‘I wanted to offer content that people – not necessarily art people – could understand’. Her work is truly egalitarian in this respect. It is open to everyone and encourages all forms of engagement, even negative. In an interview with The Guardian, she claimed she even enjoyed watching people vandalise her messages because it showed her work had intercepted their perception. It is not an exercise in gaining admiration or notoriety. In fact, this brand of self-acclaim grinds directly against the aims of her generation, whose practices were not ‘skewed by the need to sell’. Instead she aims to encourage her anonymity, allowing her Truisms to permeate society and excite emotional response outside the parameters of everyday life.

This kind of boundless expression and critical debate is louder than the preaching of information we passively receive and consume on a daily basis. Fundamentally we exist in an age where silence remains an obstacle to social progress. Subsequently, protest art is more relevant than ever. Holzer and other proponents of this art form, motivated by a desire for social justice, force discussion and challenge the dominant societal narratives in a democratically enthused framework. The noise they generate will prove imperative in breaking through the silence which acts as a bulwark to social justice on a daily basis.

Featured image source: Tate.org.uk.

Jenny Holzer’s Artist Room at the Tate Modern is on display until Summer 2019.