GEORGIA GOOD reviews In America: A Lexicon of Fashion at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In America: A Lexicon of Fashion, opened by the Met Gala last month, starts with a question. Prabal Gurung’s sash dress (‘Belonging’, 2020) asks, in red, white and blue, ‘Who Gets To Be American?’. Urgent and perennial, this question is always present – in the rooms of the exhibit and the museum at large, in the minds of Americans and the world.

In 1984, Jesse Jackson called America ‘a quilt – many patches, many pieces, many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread’. This conceit is the basis for the Met Costume Institute’s annual exhibit. Thus, Tristan Detwiler’s jacket and trouser ensemble (‘Togetherness’, 2021) – made of reworked, nineteenth-century patchwork, an exhibit-wide motif – literalises its title. Adeline Harris Sears’ actual quilt, begun in 1865, is signed by some of the greatest-known Americans of her time. In America, with about a hundred ensembles woven into one whole, itself enacts the metaphor. As the head curator, Andrew Bolton, told Vogue: ‘the idea of reducing American fashion down to one definition is totally antithetical to what the exhibition is about’.

In its pursuit of inclusivity, In America: A Lexicon of Fashion looks not just to high fashion, but the average American closet. As you pass a Heron Preston jumpsuit or a Tom Ford dress on display, the thought ‘I’d wear that’ feels closer – more real than the ‘I’d wear that’ directed at New Bond Street, or the Met Gala itself. Institutions like the Met are always on the edge of elitism, always under pressure to resist it; Bolton clearly intends to do so, to expand its reach beyond what, to most visitors, will always remain behind the glass.

The space itself is like a surreal, scaled-up, thoroughly immersive walk-in closet (a kind of closet which has always felt American to me, in its deeply domestic extravagance). Subterranean and gridlike, it is labyrinthine yet ordered, dreamlike yet precise. Muted, emotive music, Julius Eastman’s Femenine (1974), murmurs over monochromatic lights, right angles, varied outfits in identical forms. True to the Great Experiment of early America, the show exalts democratisation (and capitalism, of course). Eckhaus Latta’s ‘Admiration’ (2015) resists the default, exclusionary Eurocentrism of much high fashion: their great cloak, woven together from reworked tapestries, is loud, defiant, regal – a modern, eco-minded reimagining of a dusty European monarch’s robes. In this, In America departs from recent years’ themes, like Heavenly Bodies (2018) and Camp (2019) – Catholicism is profoundly hierarchical, and camp, with its elusive intellectualism, turns out to be, too.

This shift is clearest, perhaps, in the show’s implicit narrative on gender expression. In America reveals a sustained, democratic focus on utility in American fashion, over aesthetics and established tradition – introduced via Claire McCardell’s wraparound dress (‘Honesty’, 1943), and from there, increasingly testing the boundaries of binary gender. McCardell’s ethos is developed by Halston’s camel shirtdress (‘Fluency’, 1974), adapted from men’s shirt designs; Donna Karan’s women’s blazer (‘Conviction’, 1985), with its broad, boxy shoulders, asserts both ease of movement and traditional masculinity; Erl’s sports jersey, leggings and short shorts, ‘Cameraderie’ (2021), is institutionally boyish, yet playfully homoerotic, conceived in the ballpark and locker room alike. In America hints towards how functionality and comfort eroded separate-spheres fashion (and thus, its values), all the way up to today, the peak of formless athleisure. Emerging designers like Erl’s Eli Russell Linnetz, who have a strong presence in the show, fully capture this genderless all-inclusivity. Telfar Clemens’ off-shoulder tank top and utility trousers, ‘Self-Determination’ (2019), is the epitome. After all, self-determination is a highly American ideal, reworked here to envision greater authenticity, inclusivity and freedom of expression – in the spirit of the Constitution, but for real this time. Even Telfar’s tagline – ‘not for you – for everyone’ – sounds like a reimagined echo of the Founding Fathers’ original supposed vision.

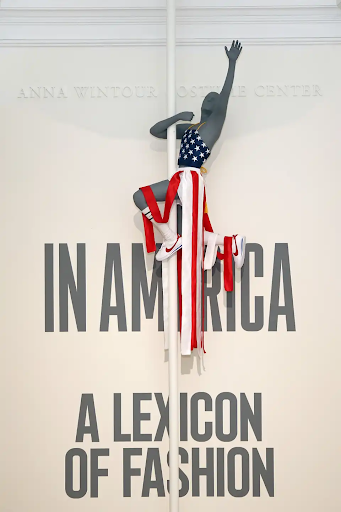

This evokes the optimism of In America, and the American story at large. As you enter, a mannequin ascends, arms outstretched, in a Gypsy Sport stars-and-stripes leotard, streamers, and red and white Nikes, exalted, over a colossal ‘IN AMERICA’. From the age of Manifest Destiny, this was the American dream: patriotic, visionary, triumphant – even when its deeply dark side went unmentioned. In America is not above that romanticism. There is a grandiosity in the nouns that title each ensemble, a sense that fashion is greater, more profound, if labelled with abstract, evocative terms like ‘Connection’ and ‘Reverie’. It is clearest in the American flag sweaters on display, conceived by Ralph Lauren in 1989 and Tommy Hilfiger in 1992. These sweaters show America itself as a brand – how its consumerism is self-fulfilling, so that America commodifies itself. Its quintessentially American, egoistic hubris, is easily something to sell, the legacy of an ‘America: We’re Still Number One’ psyche. The popularity of Lauren’s and Hilfiger’s designs, and the success of brands like Levi’s, Hollister and American Apparel, are the natural fate of those stars and stripes in fashion.

Thus, In America considers the influence of Americana, and the all-American preppiness of ball games and cheerleading. Perry Ellis’ sweater is monogrammed with a Princeton ‘P’ (‘Fellowship’, 1978); Tommy Hilfiger’s red, white, blue and gold cable knit borrows its enormous ‘H’ from Harvard (‘Association’, 2018). This not only pays tribute to collegiate, varsity style, but enacts another democratisation: by commercialising the Ivy League aesthetic for the mainstream, these designers can undermine its elitism. This, too, speaks to American fashion as semiotic, consisting of emblems, symbols; the term ‘Lexicon’ is well-chosen by the Met. Its language is the American flag, the letterman, and is equally used to question those terms, to expand the lexicon – as in Willy Chavarria’s sweater’s upturned flag, its stars falling from it (‘Isolation’, 2019), and Tremaine Emory’s cotton wreaths, embroidered onto classic Levi’s denim (cotton is a symbol of slavery, on which its production depended (‘Consciousness’, 2020).

There is a sense in the show that the lexicon is incomplete – that America is not quite fluent in its own language, and has not yet decided ‘Who Gets to be American’ or, indeed, what matters in American fashion. In America projects all the right values (inclusion, diversity, sustainability), but is not fully sure of past or present. Like a high school football star in varsity fashion, both America and the exhibit seem great, but uncertain, not as assured as they’d like us to believe. In America reaches from the 1940s to today, but its beginnings feel arbitrary, indistinct; there is little text on display. By not fully engaging with the past, much of its meaning is unclear; where are the Indigenous clothes, the early colonial, the antebellum hoop skirts my mother wore in Mississippi, dressing up for tourists? How does the past inform the present, and how are the two defined? In America’s subject is a still-young nation, wrestling with its origin stories; the show’s absence of narrative is therefore deeply felt.

Yet this, itself, evokes the American experience (not to mention the bright and gridlike, incomplete, overwhelmingly visual way we increasingly see the world). It is an individualistic experience; the monolexical labels and layout are evocative, not informative; emotive, not didactic. There is a sense that as you walk through it, you’re on your own. Take from it what you can. Yet like Jesse Jackson’s quilt, each piece, ensemble, visitor (unusually this year, most visitors are American, after Covid regulations tightened US borders), is stitched together. From this, America – loud, diverse, uncertain, despicable, sublime – starts to emerge.

In America: A Lexicon of Fashion is open until Autumn 2022 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Part Two, In America: An Anthology of Fashion will open in May 2022.

Featured image: Sterling Ruby’s Veil Flag, 2020. Image source: Melanie Schiff.