CHLOE TYE interviews Natalie Haynes about Aristophanes’ comedy Lysistrata

On meeting Natalie Haynes, one of the first things that struck me is the speed at which brain her works, and for the remaining time I attempted to keep up with her as best I could. This article is a result of half an hour spent in her company, during which my brain was thoroughly exhausted. I want to extend a thank you to Haynes for taking the time to participate in this interview.

After completing a degree in Classics at Christs College, Cambridge, Natalie Haynes went on to pursue a career in comedy, having been a member of Cambridge University Footlights Dramatic Club. In addition, she is now a writer, both as a journalist for the Guardian and the Independent and as an author of fiction and non-fiction, as well as a regular contributor for BBC Radio 4.

With her experience in comedy, Haynes has perhaps a unique view into the art, particularly regarding how the ancient genre has seeped into the modern. She has a staunch dislike of Menandrian comedy – predominantly character-focused and domestically-based without concern for current affairs or politics – which has been the main influence upon British comedy from Shakespeare to modern-day sitcoms. Instead, she prefers the provocative nature of Aristophanic comedy, and laments that his offensive comedy hasn’t survived so well as that of the ‘safer’ Menander. When I ask what Haynes thinks the reasons for this are, she proposes that it is to do with what particular purpose comedy has in British society. Rather than grotesquery and exaggerated humour, people now seek escapism in comedy — escapism that the Menandrian seems to provide.

One of the first things that Haynes mentions is that all Aristophanic comedy is based on a principle of opposition, whether that be old versus young, as in Wasps, human versus animal, as in Birds, or male versus female, as in our play, Lysistrata. These binaries reflect and discuss conflict found in Aristophanes’ Athens; modern productions of ancient plays are an excellent way to display and comment on such conflicts that persist to this day.

Our production is set in the English Renaissance: a pivotal period for the progression of western proto-feminist thought that emerged through the writings of Thomas More, Thomas Elyot, Juan Vives, and Boccaccio, who argued that extending social privileges reserved for men, such as education, to women might be beneficial to the nation. In this way, we are able to trace the gender politics of Aristophanes’ time, where men and women’s roles in society were categorically distinct and divided, through British history to our own present. We have progressed leaps and bounds from ancient Athens in terms of gender roles, particularly with regard to the role of women in society; however, this play clearly still strikes a chord with us — this is UCL’s fourth production of it in the last twenty years.

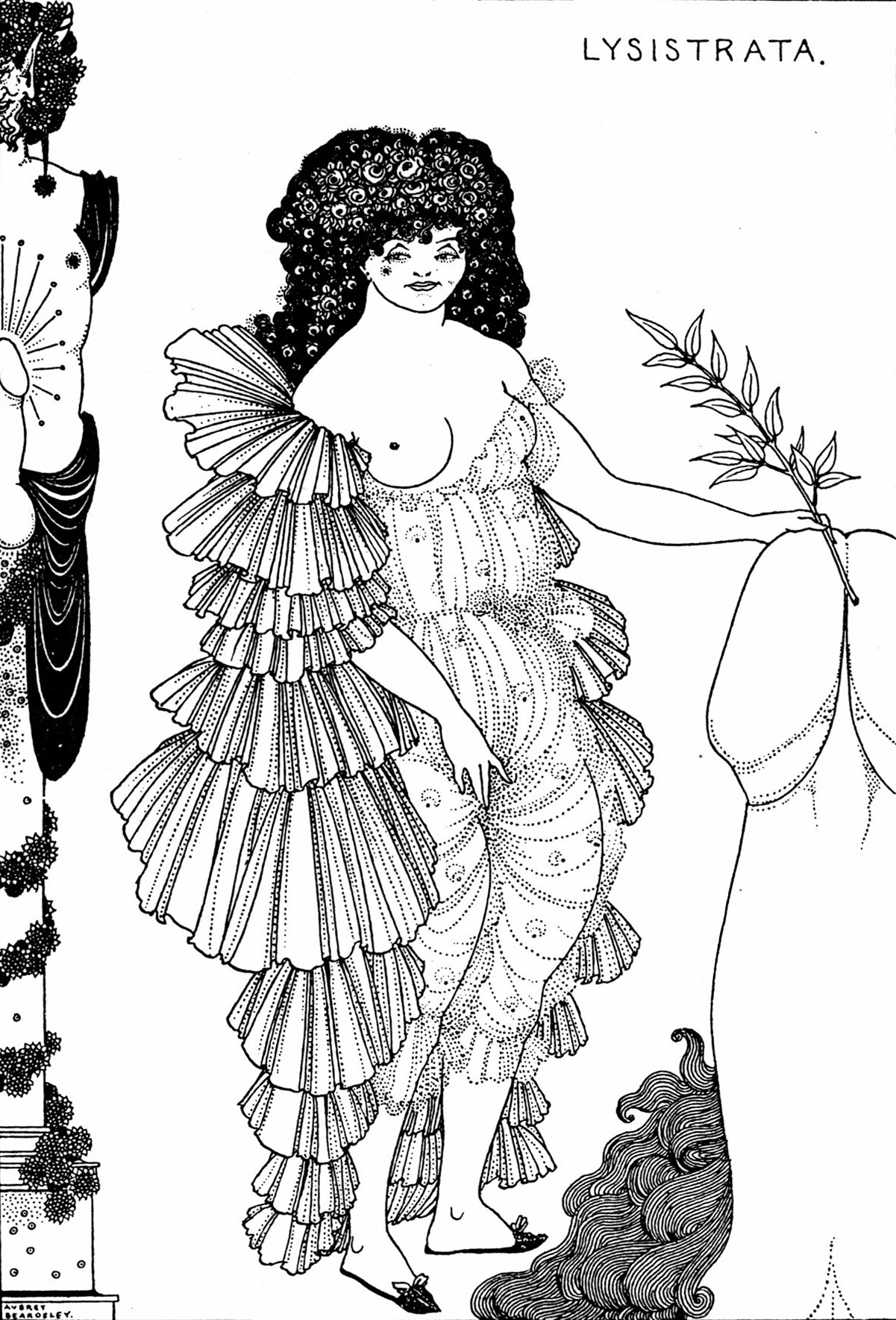

Lysistrata’s story of women opposing Athenian men and their patriarchy, Haynes says, is not necessarily Aristophanes’ promotion of a feminist agenda, although many be interpreted as such. His discussion of gender is possibly just a way of using an opposition to discuss his favourite topic: the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. Indeed, the notion of women being in power would have been laughable for the Greeks, and the drama’s plot a fantastically absurd one. When I asked Haynes if she thought the eponymous Lysistrata was intended to be a comic character, to my dismay she said yes: though she is taken as a feminist symbol nowadays, it is most likely that she was intended to act as a comic counterpart to the men in the play. However, she assured me that she is most certainly the play’s protagonist, pompous and sanctimonious, but characterised as hero by these very flaws. Aristophanes’ plays are never a case of good versus bad, but rather one opinion versus another, both valid and problematic in their own ways — and, at times, ridiculous.

But, just because Aristophanes didn’t intend Lysistrata to be taken seriously, it does not mean that we cannot do just that, and even recast her as a symbol of female political power. Plays develop meanings of their own over time. When we hear Lysistrata’s speech comparing Athens to a skein of wool, describing how she will purify the city using a domestic metaphor of spinning, we can interpret a bridging of the gap between the male and female social spheres and the deconstruction of gender roles. We can be inspired by her rallying the women of the city, and by her strength in the face of mockery by the Athenian institutions and their representatives. Indeed, one of the reasons why this play has survived so well is because of its adaptability to contemporary gender politics, and the positive message it can be seen to put forward.

Haynes compares Aristophanes’ portrayal of women with that of Euripides, infamous for his dark and vengeful female characters, the most famous of which is probably Medea. Greek drama tended to give women a freedom they did not have in their everyday lives – they are the protagonists of many plays, wreaking havoc on their husbands and families, and the establishments which confine and oppress them. One explanation for this presentation is that it acts as a warning to Athens: ‘this is what women will do if they take power for themselves’. However, Haynes states that Aristophanes was a repeated mocker of Euripides. The portrayal of women like Medea in his plays, and therefore in Lysistrata, is potentially a jab at Euripides himself, a parody of his female characters. Indeed, Haynes says that ‘Aristophanes would do anything to get a laugh’.

As our conversation draws to a close, we discuss the role of comedy today and where Aristophanes’ place lies in it. Haynes believes our society is becoming more and more unforgiving, posing problems for modern comedy – if people in the public eye say something that is viewed as too politically incorrect, their career could be over in a matter of minutes. She herself says that she’d ‘always prefer to be offended than annoyed’. Perhaps in its own way, our production can bring the comedy of Aristophanes and his lack of political correctness into British humour, as we mark the importance of Lysistrata in British history and modern feminist progress.

UCL Classic’s Society’s Lysistrata is running from 7th-9th Feb at the Shaw Theatre. Find more information here.

Featured image courtesy of antiuniversity.org