MARISA BECIROVIC reviews Among the Trees at the Hayward Gallery and explores how these fantastic natural features should, now more than ever, be appreciated for their longevity.

In times as unstable as these, exhibitions like Among the Trees at the Southbank centre offer us an escape into the complex constancy of nature. Set out across the three levels of the brutalist Hayward gallery, these flourishes of photos, sculptures and paintings transport you into a ‘forest of art’, which softens the gallery walls and opens a window into a world we seem to have lost touch with in recent years (though which many of us have rediscovered during lockdown). Among the Trees explores the range of interactions humans have with trees. Often perceived as ordinary or mundane, this exhibition reminds us of these fascinating, versatile and frankly invaluable structures all around us. Through photography, paintings, sculpture and visually interactive installations we are presented with a collection of artists’ perspectives and in turn have our own views challenged: we become aware of the limits imposed by our conventional view of nature, begin to rethink the way we interact with our surroundings, and question how harmful these interactions have become.

Thomas Struth’s collection of photos bewitchingly explores the intricacies of messy tree scenes and exemplifies the attraction of the tree as a subject in visual arts. While artists have long been captivated by the versatility of these features of nature, the medium of photography has evolved the potential to capture perspectives that excite and add intrigue to our process of viewing them. In the words of the gallery text, Struth persuades the viewer to ‘surrender to just looking’, commanding them to avoid dissecting the image and just absorb the power of a natural scene.

Trees have always been used as a symbol of enlightenment and inspiration for artists, but the collection of works in this exhibition gives a more modern take on artistic interactions with our leafy surroundings. The more interpretive and experimental angles of nature we see in this collection confirm the endless ways in which we can artistically interact with it. Rodney Graham’s work literally turns the world upside down, creating an uncanny experience of viewing. His photo Gary Oak, Galiano Island (2012) confuses the viewer, with the inverted tree at its centre. It no longer holds the wonted form of branches and leaves outstretched to the sky and we are confused and intrigued by the new perspective. Hugh Hayden uses ‘something as ubiquitous as a tree to change someone’s perspective’ as explained in the gallery text. He recreates the structure of two logs in his piece Zelig (2013) by manipulating sharp-tailed goose feathers until they resemble the familiar texture of bark. This sculpture plays with the theme of camouflage in nature but also provokes us to consider that the natural world is not always what it seems: it still holds the power to surprise us. Roxy Paine highlights the deep biological connection we have with our surroundings through her profound sculpture Rotoplasm (2012), composed of stunningly intricate tree-like structures made from enamel. The use of striking red paint creates a biological association in our minds, as we suddenly see trunks and branches as arteries and capillaries pumping oxygenated blood around our bodies, no doubt a comment on the gravity of our need for trees to provide clean air and ensure our survival.

The exhibition also showcases trees as symbols and landmarks for significant events and changes in human history. While trees have quietly and statically existed, frequently unobserved, their surroundings have evolved and events passed them by: they serve as a camera lens registering the world around themselves. Tacita Dean turns the camera around on the oldest living tree in the UK, giving us a reflection of the length of time this venerable yew has absorbed into its layers of bark. Now in its ancient life, the tree is supported by crutches, adding a very human validation to the significance of this living being. The tree has transcended to the status of a sort of ‘elder’, wise and rich with all it has observed. Steve McQueen’s photo Lynching Tree (2013) depicts a scene of sinking graves, towered over by an enormous tree, which upholds the memory of the atrocities committed in Louisiana during the time of slavery. It acts as witness to such atrocities and signposts the physically intangible marks we have made on our societies.

The impact of human activity has, however, left its scars on the environment, something Among the Trees does not shy away from displaying. Our natural surroundings inspire us, provide tranquil sanctuaries for many of us, but they have faced the consequences of our rapid industrialisation and wasteful culture. Zoe Leonard captures the modern fusion of nature and man-made infrastructure through her 1998 photo series depicting trees engulfing obstructive structures in their surroundings. Whilst the photos are rather unnerving, as we see the desperate struggle of nature against human entrapment, there is also a continuing sense of resilience. Leonard describes the series as ‘images of endurance and symbiosis’ which seems to honour the surprising behaviour of nature.

In contrast, more profound and violent effects on nature, which have been prevalent in the media in recent years, were clearly at the forefront of other artists’ minds. Symrin Gyll’s conflictingly beautiful photographs show plastic waste enshrined in the natural haven of the Malaysian coast, depicting the ugly effects of pollution. The paintings of George Shaw subtly hint at human interaction with nature: he paints a forest scene with an ironic stark white heart graffitied on a tree trunk. Art continues to act as a medium for highlighting social issues and prompting our attention to change. One of the most striking installations of the exhibition was Desolation Row (2017), Roxy Paine’s violently burned landscape scene engulfed in black soot and charcoal, with the last red embers illuminating harrowing silhouettes of dead trees – a terrifying reality. With forest fires raging in California, the devastating effects of human activity explored in the arts touches a nerve for many of us right now.

The artworks in the exhibition Among the Trees serve to bridge the gap that has grown between us and our natural surroundings, and to honour the complexity of the profound relationship we have had with trees since the beginning of our documentable existence. It seeks to bring back our attention to the delicately overwhelming beauty of trees, illuminate perspectives we haven’t considered and challenge our ideas. The exhibition gives a varied and realistic presentation of the modern world, as it seems it is becoming all the more important for us to confront the way we see nature. Now more than ever, it is imperative that we focus on the details of our environments in order to see the bigger picture: it is our engagement with our immediate surroundings that show us the brilliance of their random design, their fragility tangible to us with an outstretched hand on crumbling bark. Maybe we all need to look away from our technology, away from the rush of information we all receive daily, and see that our natural surroundings, the most ordinary of things, hold a much deeper significance to humanity than we might have previously thought. This exhibition forces you to realise that trees really aren’t ordinary at all.

Among the Trees is being shown at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre until 31st October 2020.

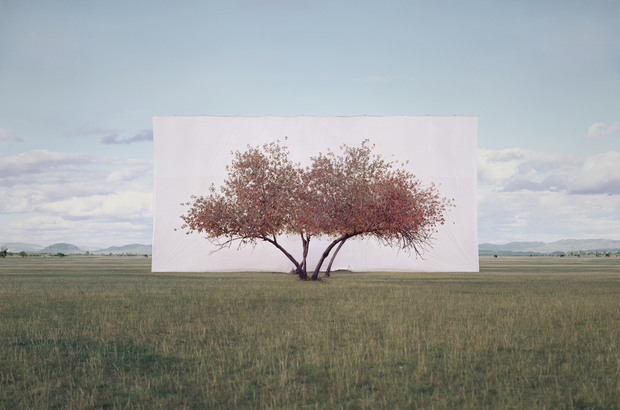

Featured image: Myoung Ho Lee, Tree… #2, 2011, inkjet print, 104.1 × 152.4 cm. Image source: British Journal of Photography.