EVIE ROBINSON reviews the Royal Society of Portrait Painters Annual Exhibition and ponders the effect of the visual exploration of the personal.

The ultimate intention of portraiture is to represent the individual; to capture the true spirit of the person at the heart of the work. Portraying the accurate likeness of a subject means working into the canvas an essence of their personality, their unique mannerisms, their individual qualities and quirks. The individuality of those who were depicted in the works displayed at this year’s Annual Exhibition by the Royal Society of Portrait Painters is striking.

I gravitated towards the family portraits in the exhibition. These pieces endeavour to capture for the viewer what is normal for a particular family, what makes them distinct from others. Joe and his Family, painted by Susan Ryder, is unique in its depiction of multiple generations of a family gathered together in one room for a photograph. In a similar way, Anthony Morris’ portrait entitled The Jigsaw Puzzle depicts women from several generations of a family, united over the task of completing a puzzle. Melissa Scott-Miller’s portrait Islington Family plays on the juxtaposition of the specific interiors and idiosyncrasies of a family home, and the vast surrounding space outdoors consisting of many similar-looking houses. The suit of armour in the corner of the room and the Victorian architectural features of the home contrasts with the more modern metal desk chairs on which the parents of the family are sitting. Scott-Miller reminds us with her work that behind each door is a group of individual stories, which the outside world is rarely privy to.

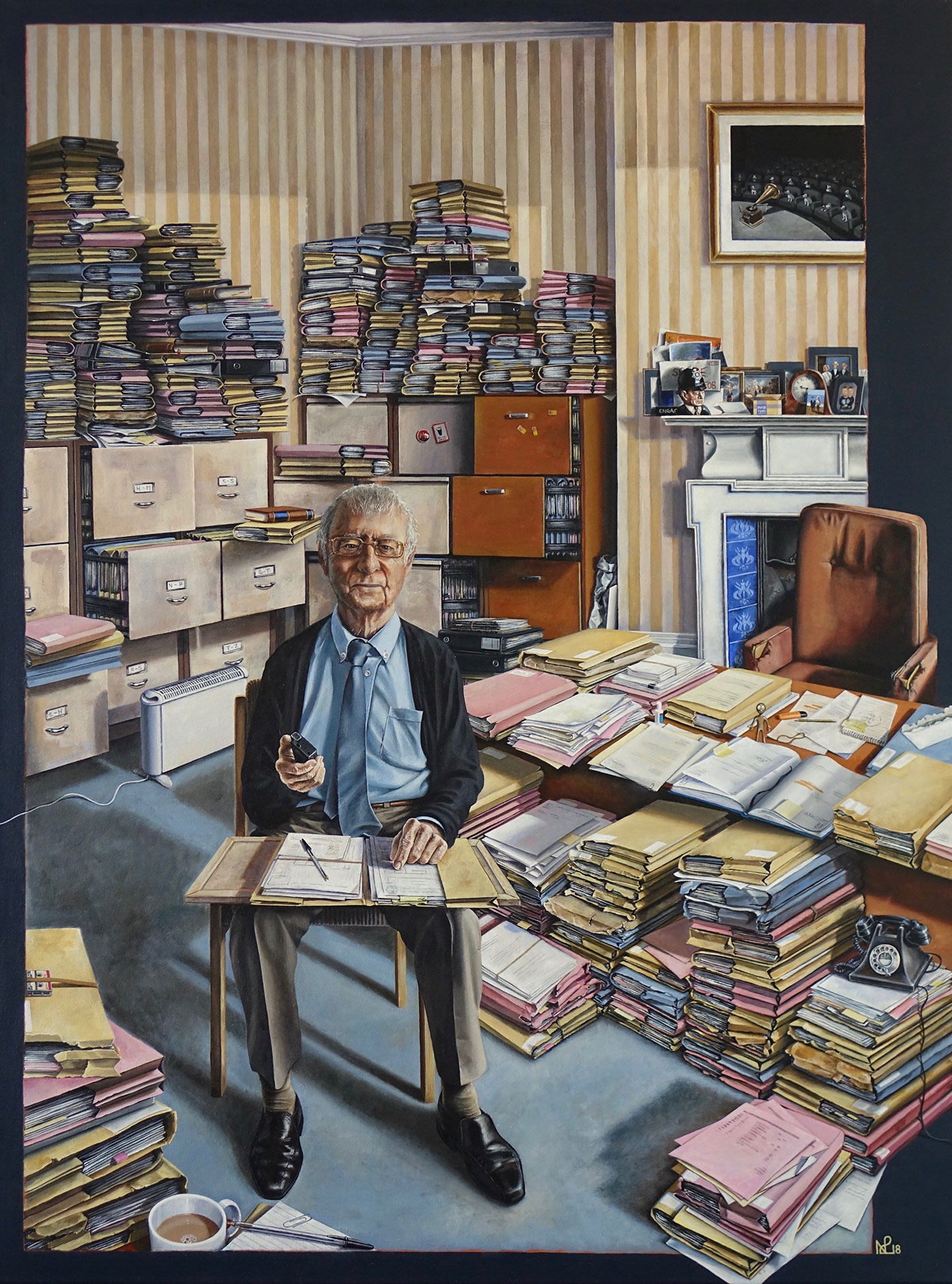

One portrait that really stood out for me was My Father, A Life of Work, painted by Nicholas De Lacy-Brown. It is an incredibly powerful image; the light blue colour of his shirt matching the colour of many of the folders surrounding him, perhaps suggestive of an intricate link between the man’s personality and passion for his work. Positioning the subject in the centre of a small room surrounded by an abundance of folders, papers and books shows us the vast trajectory of his working life. I felt this image in particular demonstrated the value of portraiture as a timeless and valuable piece of memorabilia; for many people this is the driving reason behind commissioning a portrait. Portraiture is perhaps one of the best ways to uniquely capture one’s sense of self. Not only is a portrait something one can treasure for the rest of their life, but it is a valuable implement in inspiring and educating future generations about a person’s legacy. Being at the heart of the creative process when sitting for a portrait is undoubtedly an invaluable experience; you have the ability to weave the specificities of yourself into an artwork and focus on both imitating real life and creating a unique presentation of the self. Regardless of its relative status in the fine art world, a portrait is a timeless piece of art, simply because the process of making is always so tailored to the individual; the piece will always belong uniquely to you.

Portraiture allows us to consider what it means to be human, this exhibition confronting us with works of art that are so innately personal. Belinda Crozier’s Ruth, 24 Weeks and Ruth, 37 Weeks particularly highlight this. The two contrasting portraits, painted at different points of a woman’s pregnancy, from slightly different angles and with different clothes, portray the gradual change and evolution involved in pregnancy and the growth of new life. This portrait had a profound impact on me, as I sensed it did for several other people viewing the exhibition; the way in which the woman depicted completely embraces her state of vulnerability and exposure paid homage to the strength of the female body when enduring pregnancy, and the power a mother has in bringing a new life into the world. This same vulnerability is captured beautifully in Alastair Adams’ Love Disfigure. Sylvia Mac, who is represented in the portrait, detailed in an interview how she felt a sense of liberation when sitting for Alastair to paint her. For so long, she said, she had suffered with depression as a result of the scars on her body not being accepted in mainstream society as a form of beauty. I have unbounded respect and admiration for Sylvia for being brave enough to share her story in such a manner.

Portraiture is an art form that draws on the individual; the ways in which we are set apart from others, and the intricate details that are specific to each of us as human beings are exposed and illuminated. I left the exhibition feeling as if I had met and experienced an entirely new group of people. It was a truly enriching and engaging experience, and reminded me of the incredible wonders of humanity.

Featured image: Susan Ryder, Joe and His Family, oil, 112 x 142 (132 x 162 cm framed). Image source: susanryder.co.uk