MAYA SALL reviews Toyin Ojih Odutola’s exhibition A Countervailing Theory and considers the often inaccessible nature of exhibition spaces.

When transitioning from the light of the outdoors into the dimly lit and monochromatic Curve gallery, part of the Barbican Centre, you immediately feel immersed in a new world. Such a feeling is no coincidence. In Toyin Ojih Odutola’s first UK exhibition, A Countervailing Theory, an ancient myth of a fictional, prehistoric civilisation is narrated through stunning drawings done with pastel, charcoal, and chalk.

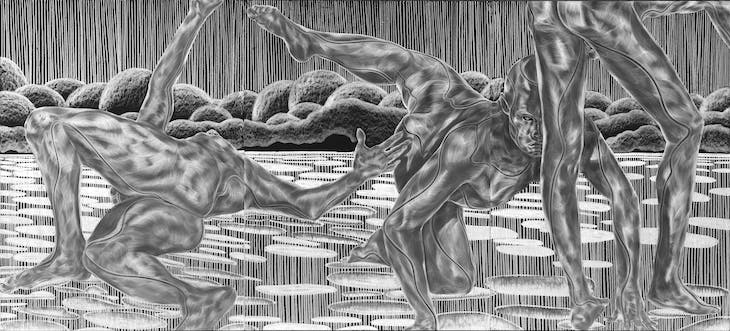

Both the beauty of the drawings and the skill of Ojih Odutola’s artistry are undeniable. Through simple materials, she conveys the ethereal beauty of an extinct civilisation. Soft highlights of supple muscle make the figures’ skin appear silken, especially in contrast to the background of rocky landscapes inspired by the Plateau State in Nigeria, their jagged textures built up through intricately layered mark-makings. The luminosity of the figures holds your attention. Their piercing white eyes cut through the dark room, daring you to look away. This feeling of being watched, coupled with the rich, percussive soundscape, composed by Ghanaian-British conceptual sound artist Peter Adjaye, creates an atmosphere of suspense and anticipation. The curved wall of the gallery contributes to this apprehension also; as you move from drawing to drawing, you are unable to see what is around the corner.

However, it was not only the rest of the gallery that I was struggling to see. Ojih Odutola’s exhibition is sold as a collection of works which possess their own interior storyline: ‘each of the works act as an individual episode within an overarching narrative’. I love ambling around art galleries, but I cannot boast of having the most extensive knowledge of the art world. Therefore, an exhibition containing artworks which appeared to explain themselves was instantly inviting; supposedly, no prior knowledge would be needed, and I would not need to exert too much brainpower to unlock the meanings of these images.

At the start of the exhibition, you are told that the civilisation depicted was matriarchal, upheld by male labourers, and that only same-sex relationships were allowed. After that, the viewer is encouraged ‘to piece together the fragments of the story for themselves’. This was altogether quite difficult to do when the only information given was convoluted and riddled with indistinct jargon: ‘[Ojih Odutola] weaves speculative tales, which question familiar histories and pose alternative realities’. It is no wonder we are directed to the works themselves to understand this cryptic narrative, as the information provided is so sparse. It really is down to the imagination of the viewer to understand the rest.

For some, this invitation to imaginative creativity may be freeing, but I could not help but find it overwhelming. Instead of getting lost in the narrative of the images, I found myself very self-consciously trying to articulate their meaning, with little or no success. Instead of feeling inspired, I felt frustrated; even a little stupid.

Consequently, my thoughts got lost; but not, I expect, in the way that Ojih Odutola or the curators at the Barbican hoped for. Instead, I found myself asking ‘what is it that really makes an exhibition accessible?’. This exhibition is free, so I would assume that it was trying to reach out to a younger audience, and encourage those who might not have the funds to frequent galleries to engage in art. This is undeniably a positive thing, especially when, according to the 2018 Museums Audience Report conducted by Audience Finder, 16-24-year-olds make up 15% of the UK population, but museums attract only 10% of this age group. However, while the freedom of imagination in Ojih Odutola’s artwork may feel less constricting for some, I can’t help but feel that the jargon-riddled introduction and expectations of the viewer’s powers of deduction would put pressure on first-time or infrequent exhibition-goers that would lead them to feel isolated from the artwork. This was certainly the case for myself.

I am not trying to advocate for art to tell us what to think. Its purpose is to do the opposite, and Ojih Odutola certainly did this by highlighting themes of gender, sexuality, and colonialism. However, the purpose of an exhibition differs from that of art. As corny as it sounds, an exhibition’s purpose is not just to ‘exhibit’, but to educate and inspire, especially when trying to attract a younger audience. This exhibition just did not do that for me.

If you are looking for an exhibition to sink your teeth into, as you meander around for a couple of hours, then sit this one out. However, if you are looking for something to briefly lose yourself in (be it through imagination, confusion, or somewhere between the two), then head to the Barbican and check it out. Seeing Toyin Ojih Odutola’s A Countervailing Theory has taught me that it is best just to take every exhibition for what it is offering. It is possible that the fractured, stop-motion narrative of consecutive drawings is deliberately hard to grasp. Maybe this intangibility is Ojih Odutola’s way of reminding us that in a chaotic and fragmented world, our singular narrative is never enough to understand the full picture.

A Countervailing Theory is on display at The Curve until 24 January 2020. Admission is free, with pre-booking essential.

Featured image: Toyin Ojih Odutola, Imitiaition Lesson; Her Shadowed Influence, 2019, from A Countervailing Theory. Image source: The Barbican.