MAYA BOWLES discusses how her experience of Small Island has evolved in light of the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement.

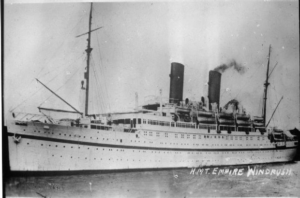

The National Theatre’s production of Small Island, broadcast for one week on their YouTube channel, coincided not only with the second annual Windrush Day on 22nd of June, but also with the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. I first saw the play last August at the National Theatre, and while I thought it was outstanding then, watching it for a second time online during the coronavirus pandemic and the BLM movement gave the story a new gravitas. Based on the novel by the late Andrea Levy, Small Island moves between Jamaica and Britain, telling a story that spans the Second World War, and the arrival of the HMT Empire Windrush in 1948. In a recent interview for The Guardian, Leah Harvey (who plays Hortense) said that ‘Doing this play is a contribution to sharing the historical story of why our country is the way that it is’. Simultaneously heart-breaking, vibrant and comedic, the play details the lives of two British and two Jamaican characters, as they become increasingly intertwined.

The experience of Gilbert Joseph (Gershwyn Eustance Jnr) and Hortense (Leah Harvey) as they arrive in England from Jamaica represents that of many hopeful Caribbean people who sought better lives in the ‘Mother Country’. What the play manages to depict so movingly is the stark contrast between the Caribbean idealisation of British life, as a result of the promises of the British government, and the bleak reality of racial prejudice in England. After signing up to fight for Britain in the Second World War, Gilbert is posted to Lincolnshire. To his amazement, the Lincolnshire locals have never even heard of the West Indies, asking ‘Is that in Africa?’. Despite Gilbert’s experiences of racism in the army, he remains fervently patriotic about Britain, never giving up on his dream to start a new life in England. He says of Jamaica, ‘I am done with this small island’. Instead he longs for a life of opportunity and prosperity in the ‘Mother Country’. Yet, after arriving at Tilbury on the HMT Empire Windrush, Gilbert’s dream is crushed – he is unable to go to university to study law but forced instead to work as a delivery driver, to live in squalor, and to endure abuse on the streets.

The 2017 Windrush Scandal highlights that the kind of hostility and racism Small Island depicts is still deep-rooted in British society today, 72 years after the play was set. Like so many others, Hortense and Gilbert began new lives in a country that promised them everything, yet treated them as second-class citizens. After Theresa May’s introduction of the ‘Hostile Environment’ policy in 2012, many of the Windrush generation who had lived as British citizens for decades were fired from their jobs, deprived of healthcare, housing and access to public services. The Home Office also demanded at least one official document from every year an individual had lived in Britain. This was an impossible task seeing as many of the Windrush generation arrived as children on their parent’s passports and the Home Office had already destroyed thousands of records. The ‘Hostile Environment’ policy subsequently led to the wrongful detention, deportation, and denial of legal rights to hundreds of legal citizens from the Commonwealth. An independent review into the scandal by Wendy Williams, published in March 2020, said that the actions of the department demonstrated ‘ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race and the history of the Windrush generation.’ While Williams is hesitant to identify ‘institutional racism’ within the department, the BLM movement has highlighted that ‘ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race’ are indeed forms of systemic racism. What many people have learnt from BLM is that it is no longer enough to be non-racist – instead, we must be anti-racist. The Conservative government’s ‘ignorance and thoughtlessness’ has repeatedly failed the Windrush generation and their families. Despite the government’s introduction of the Windrush Compensation Scheme in April 2019, 95% of victims who have submitted claims have received nothing. On top of this, the ‘Hostile Environment’ policy still exists.

It is often said that the role of theatre is to hold up a mirror to society. Small Island reminds us of the hardships faced by the Windrush generation and their invaluable contribution to contemporary Britian. It reminds us that, although we like to believe that we have improved race relations in the UK since 1948, institutional racism remains ubiquitous in Britain in 2020. The Windrush scandal, the Grenfell Tower Fire, and the recent report that BAME people are disproportionately affected by Covid-19 have exposed the insidiously systemic racism within the Conservative government and British society at large. Whilst watching the National Theatre Live plays throughout lockdown has been a source of joy and distraction for me and my family, watching Small Island was a different experience. The play is a timely reminder of the anti-racist work that needs to be done at both a societal and an individual level in Britain.