PHYLLIS AKALIN reports on UCL’s LGBT+ Network’s Stonewall Screenings, exploring what the selected films can teach us about intersectionality and their relevance to the BLM movement.

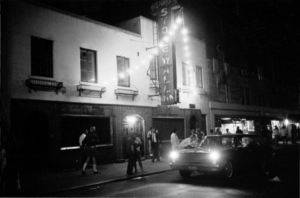

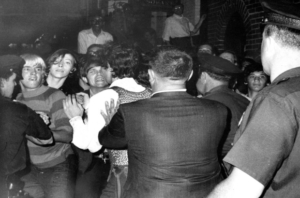

‘It really should have been called Stonewall uprising. They really were objecting to how they were being treated. That’s more an uprising than a riot’. It is with these words that the American journalist Howard Smith recalls the events which took place 51 years ago at the Stonewall Inn. In the 2010 documentary Stonewall Uprising, Smith and other contemporary witnesses reflect on the spontaneous demonstrations held by members of the LGBTQ+ community in 1969 New York City. This monumental uprising was a reaction against the violent police raids of the Stonewall Inn, one of the few gay bars in the neighbourhood of Greenwich Village at the time. Today, the Stonewall uprising is considered to mark the beginning of the global gay liberation movement and is commemorated as part of the annual celebration of Pride month.

In order to celebrate and remember Stonewall and other important parts of LGBT+ history, UCL’s LGBT+ Network organised a week of online screenings, held on June 28th – July 3rd, and showcasing documentaries, fiction films and TV show episodes. As social secretary Yoojin Lee explains, the network was aiming to show diverse aspects of LGBTQ+ history, ranging from horrific accounts of gay conversion therapy to depictions of predominantly Black and Latino ballroom and house culture of the 1980s. Another aspect that was particularly important to Lee was intersectionality, particularly the representation of non-white gay couples. This is vividly explored in Rafiki (2018), a Kenyan coming-of-age film which follows the love story of two young girls in Nairobi.

Both the 1990 documentary Paris is Burning and the fictional Netflix series Pose (2018), set in 1987, celebrate the ballroom scene, a Black and Latino LGBTQ+ subculture that originated in New York City. At events called balls, people would compete for trophies in a broad range of categories, including high-fashion evening wear, town and country, and executive realness. In the ‘realness’ category, contestants compete to be the most cis-passing, blending in with heteronormative views of gender expression. ‘Realness’ means to ‘look as much as possible like your straight counterpart’, explains trans woman and drag performer Dorian Corey. ‘In a ballroom you can be anything you want. You’re not really an executive, but you’re looking like an executive. And therefore, you’re showing the straight world that I can be an executive. If I had the opportunity, I could be one. And that is a fulfilment.’ The so-called houses that are competing against each other at balls are a lot more than just teams. Often, houses act as surrogate families for young queer people who have been thrown out of their parental homes or shunned by society. ‘House’ culture provides a sense of belonging and support for young queer people, with established drag queens assuming the roles of their ‘mothers’.

Both Paris is Burning and Pose feature a diverse range of gender identities, from cisgender gay men to drag queens and trans women, all at different stages of transitioning. It is striking how many aspects from this scene are now part of both contemporary queer culture and mainstream pop culture. The expression ‘to throw shade’ for example, now frequently used in mainstream slang, has its origins in the ballroom scene. Not only does much of today’s western pop culture originate in the Black and Latino LGBTQ+ communities, the western gay liberation movement itself has its roots within these communities. Activists such as Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera helped to start the Stonewall uprising in 1969 and co-founded STAR, a political collective that provided housing and support for homeless queer youth and sex workers.

The crucial role that BIPOC members of the LGBT+ community played in the gay liberation movement, however, is only seldom acknowledged. At the 1973 Pride parade, Latina trans activist Sylvia Rivera was booed off the stage, causing her to feel that the movement had ‘betrayed the drag queens and the street people’, as she recounts in an interview a few years later. In the 2010 documentary Stonewall Uprising, there is a startling lack of diversity. In addition to failing to interview people of colour, the documentary gives air time to the white police officer Seymour Pine. Having led the original Stonewall raid in 1969, it is somewhat unfortunate that Pine has the last word of the – otherwise very illuminating and rewarding – documentary. This whitewashing of LGBTQ+ history is particularly troubling in light of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has witnessed a resurgence following the murder of George Floyd earlier this year.

The footage of the Stonewall uprising and, subsequently, of the first Pride parade, is evocative of the Black Lives Matter movement today. Other similarities between the two movements are palpable: the negatively connoted term ‘riots’ is still used to describe the events at Stonewall by officially impartial organisations like Wikipedia. The same term is prominent in the media today and seems to somewhat discredit the protestors of the BLM movement. ‘There are nicer ways to do it, but the nice ways always fail’, activist Martha Shelley quotes the civil rights anthem ‘It Isn’t Nice’ by Melvina Reynolds. The gay liberation movement was inspired by the civil rights movement and the Black Panther Party, using the slogan ‘Gay Power’ as an allusion to ‘Black Power’. The day after the first police raid at the Stonewall, other groups joined the ongoing protests, such as Black Panthers and people from the anti-war movement.

The importance of such mutual support of marginalised groups is highlighted in the drama Pride (2014), based on the Lesbian and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) campaign from 1984. After a group of gay activists in London realise that they are essentially fighting the same system as the mining community, as they are both being bullied by the police, the government and the tabloids, they decide to back them by collecting funds to support their strike. Whilst it takes some time for the small mining community in rural Wales to get used to London queer culture, they soon realise how the system oppresses and marginalises them both, albeit differently. Once they unite, they grow stronger and achieve significant successes. Pride emphasises the importance of dialogue and encounter, and, as a consequence, of vulnerable groups supporting one another. Another issue the drama takes up is the intersections of class discrimination and homophobia.

One way or another, all the selected films of the Stonewall Screening Week seem to point to the theme of intersectionality: the interconnected nature of social categories such as race, class, gender and sexuality. Those categories create overlapping and interdependent forms of discrimination and disadvantage. Black feminist scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, founder of the theory of intersectionality, stresses how different dimensions of our identities, such as gender and race, intersect and thereafter create obstacles to equality.

Pose and Paris is Burning in particular illustrate how the experiences of members of the LGBTQ+ community are shaped by those other dimensions of their identities, such as gender, race and class. Paris is Burning begins with the telling statement: ‘You have three strikes against you in this world. Every Black man has two, that is being Black and being male. But you’re Black and you’re a male and you’re gay. You’re gonna have a hard fucking time. If you’re gonna do this, then you’re gonna have to be stronger than you ever imagined’. Dorian Corey later adds, ‘Black people have a hard time getting anywhere. And those that do are usually straight’.

The LGBTQ+ advocacy group HRC (Human Rights Campaign) reports that ‘it is clear that fatal violence disproportionately affects transgender women of colour’, as they are impacted by the intersections of racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia. Black transgender woman Merci Mack is only the latest of at least 18 transgender people killed in the US in 2020. The slogan ‘Black Trans Lives Matter’ seems to be especially crucial this Pride month as the Trump administration revokes discrimination protections for Trans people.

Stonewall was an uprising, a reaction to how members of the LGBTQ+ community were being treated. The Black Lives Matter movement is an uprising, too, a reaction to the way Black people are still being treated by the police, by the law and in short, by the system. The films selected for the Stonewall Screening Week portray a reality that is the consequence of a system that is still in place. They highlight the importance of addressing intersectional discriminations and disadvantages that reinforce one another. And they show that in order to support one of the movements, you have to support them both. As Marsha P. Johnson said, ‘No pride for some of us without liberation for all of us’.

Disclaimer: I wrote this article as an ally to both the LGBT+ community and the Black community, not as a member of either. In this article, I express my opinion of the selected films and the theme of intersectionality as an ally. If, as a member of either community, you find anything I have written in this article problematic or incorrect, please get in contact with SAVAGE so that amendments or edits to the article can be made.

This article uses uppercase “Black” to describe people and cultures of African origin as used by the New York Times. More information can be found under this link: https://www.nytco.com/press/uppercasing-black/

Find the UCL LGBT+ Network on Facebook/Instagram: https://www.facebook.com/UCLLGBT

- Trailer Pose: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_t4YuPXdLZw

- Trailer Pride: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZfFvsKDuUU

- Trailer Rafiki: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QgSeBDHqv_I

- Trailer Paris Is Burning: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o47CwiJLpes

- Trailer Stonewall Uprising: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZUZKtko4R0

Pose and Haunted (Season 2, Episode 3) are available on Netflix UK

Pride, Rafiki, Paris is Burning and Stonewall Uprising are available on Amazon Prime UK

Feature Image Source: theguardian.com