MAYA WILSON AUTZEN contemplates the sanctity of the mother-daughter relationship, and how this resonates in the literary works of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley.

‘The memory of my mother has always been the pride and delight of my life’

– Mary Shelley

1797 saw the arrival of Mary Shelley (or Mary Wollstonecraft-Godwin, as she was born). But with this new life came the tragic loss of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, who passed away just days after giving birth. Wollstonecraft’s legacy came to live in the spirit of her daughter, and directed Mary Shelley throughout her life, reaching and guiding her from beyond the grave.

As an English literature student, I have always loved the Romantic period and its chaotic multitude of revolutionary, radical writers. But I did not fully grasp the significance of the fascinating mother-daughter dynamic shared between Mary Wollstonecraft and Shelley, until reading Charlotte Gordon’s biography, Romantic Outlaws. Gordon’s text alternates between the lives of the two extraordinary women, poignantly and powerfully drawing attention to the echoes of Wollstonecraft reverberating throughout Shelley’s life. Her father, the political philosopher William Godwin, taught Mary to read by tracing the letters of their shared first name on Wollstonecraft’s grave, a fact which I find beautifully sad, poetic, and fitting at the same time.

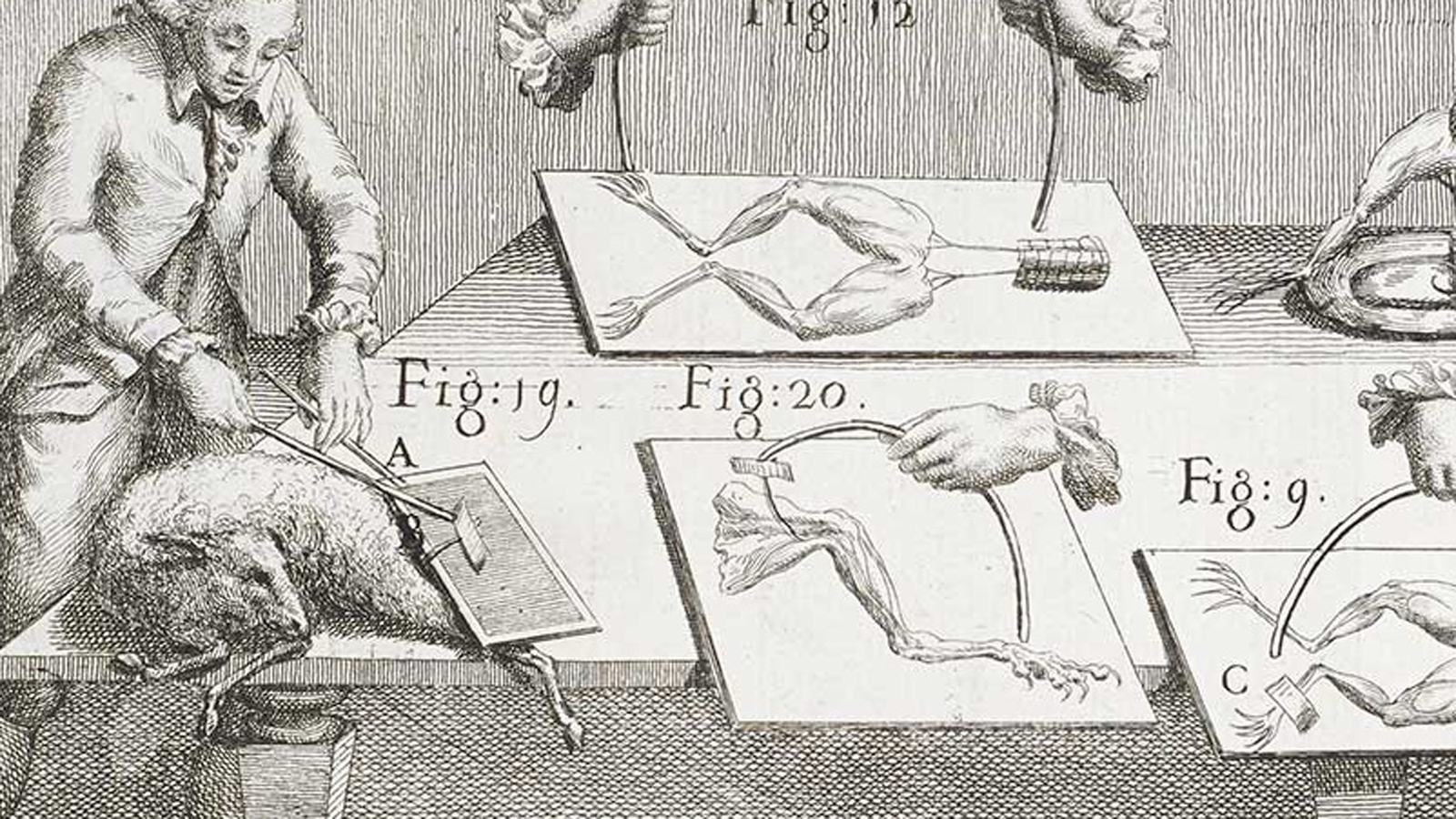

As the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, Mary Wollstonecraft infiltrated both the political and the literary scene, championing women’s rights in her proto-feminist polemic. The 1700s was a century of revolution, with uprisings in France, North America and Haiti, acting as catalysts for significant social change. Despite this, women were still unprotected by the law and controlled by the systemic patriarchal system which operated at all levels of society.

Mary Shelley also lived through unsettled political times, but focused her writing towards fiction rather than polemics, with the publication of Frankenstein in 1818. Both Wollstonecraft’s influence and absence can be read in Shelley’s novel through the centrality of family sentiment. Shelley’s sense of abandonment and loneliness from the loss of her mother, and the desire to understand her heritage and identity resonates throughout Frankenstein.

What I find most astounding is the profound, long-lasting effect Wollstonecraft had on her daughter’s life, despite being denied the opportunity to meet each other. Wollstonecraft’s maternal instinct can be seen as she addressed her future self in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, which alludes to the kind of mother she would have liked to be. For Wollstonecraft and Shelley, it seems the unbreakable bond between mother and daughter transcends life and death; their connection offers a testament to the power and strength of family – whichever form this may come in. Motherhood echoes throughout the literary canon – although it is often forgotten or unnoticed, it nonetheless exists, and is powerfully prevalent in so many texts. In Wordsworth’s The Prelude one can identify his mother’s influence through the power of nature and his preoccupation with her absence in Book V. Toni Morrison explores motherhood and race in Beloved; Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber sees the mother as a powerful heroine; Mrs Ramsay in Woolf’s To The Lighthouse is charitable and protective. The evidence of mothers’ influence in literature is perpetual.

Wollstonecraft and Shelley were ridiculed and abused by their contemporaries and rejected by even their own families. Nevertheless, they showed resilience and resolve in the face of poverty, loneliness, exile, gossip and insult. Both mother and daughter bore children out of wedlock and had to balance love and work, companionship and independence. Her mother’s legacy inspired Shelley:

‘Her greatness of soul perpetually reminded me that I ought to degenerate as little as I could from those from whom I derived my being’

Shelley worried about living up to her mother’s name but became a trailblazer in her own right, as Frankenstein continues to be relevant, speaking to issues of modern science, familial duty, our perception of life and death and the idea of God as divine creator. This duo of radicals shocked and defied their contemporaries, refusing to surrender or submit. Their writing and livelihoods were inherently radical for the time and rebelled against societal norms by their very existence. I think this quotation from Charlotte Gordon perfectly embodies the lives and legacy of such an inspirational mother and daughter:

They asserted their right to determine their own destinies, starting a revolution that has yet to end.

Both their writing and their relationship preserves the sanctity of female kinship by proving that a mother’s love does not end with death. Wollstonecraft and Shelly started teaching lessons that we are still learning today, paving the way for women to take autonomy over their writing, bodies and lives. And perhaps most importantly, their struggles remind us of the societal issues that we are yet to overcome.

Featured Image Source: Mary Shelley, The Guardian.