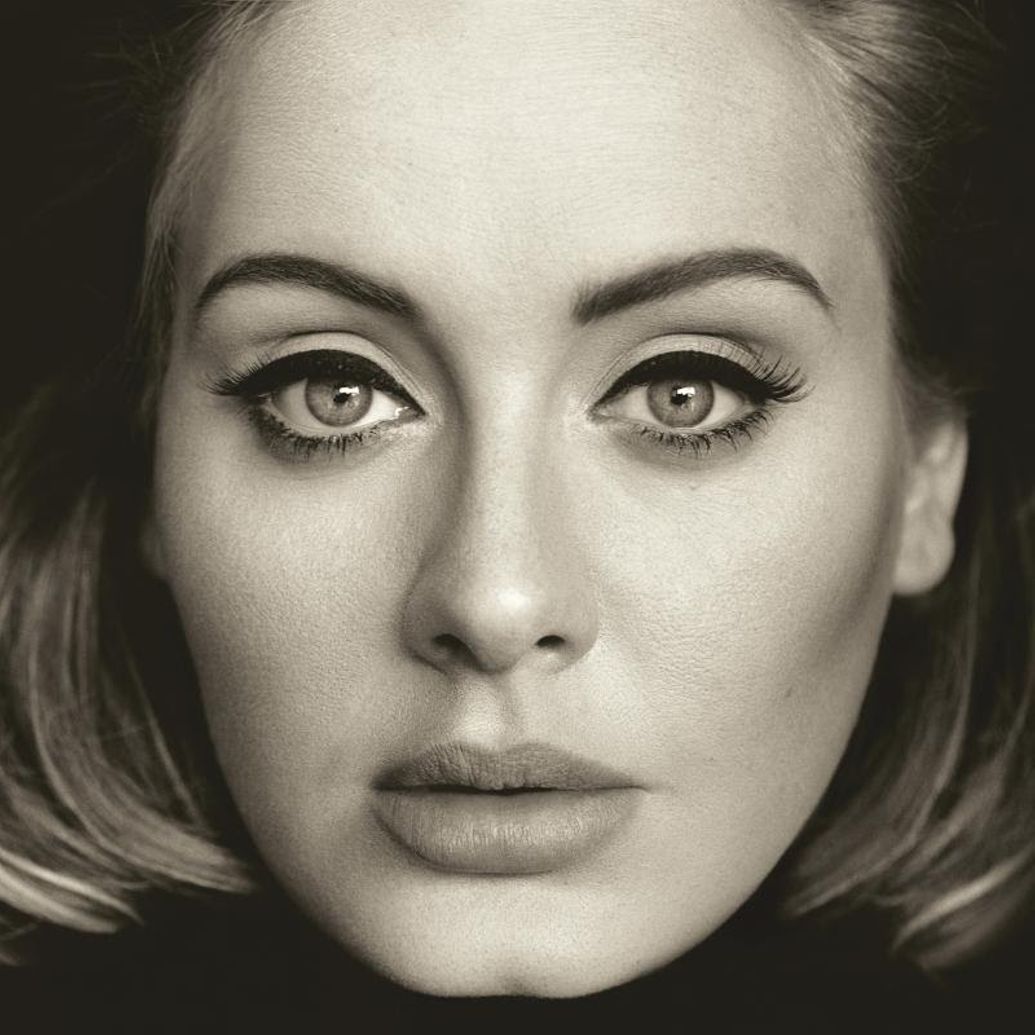

SOPHIE NEVRKLA looks at what Adele tells us about the state of the music industry.

Adele is one of the biggest superstars of our generation, with 21 being the record that propelled her from unlikely pop stardom into an international phenomenon. Globally, it is the best-selling record of the decade: as of 2015 it has shifted over 30 million copies worldwide. It is the fourth biggest selling album in UK Chart history, just behind albums by Queen, The Beatles, and ABBA, all of whom released music in an era when actually purchasing physical records was more common. 25, her latest offering, is set to break records too. It sold 300,000 copies on its first day alone, and is currently number one in 106 out of 119 countries on iTunes. Like Taylor Swift’s 1989 last year, 25 will get people talking about music differently. There will be a sense of renewed hope and optimism, and we might even think that the tide is turning: people are starting to buy music again.

Adele, sadly, is an anomaly. If she had come along at any time in the past four decades, sales like hers would still have been stratospheric, even then she would not have monopolised the charts the way she does today. Music sales are – and have been for some time – in free-fall. The top 1% of musicians who can reliably shift copies (the same regulars: Adele, Sam Smith, Ed Sheeran, Florence & The Machine) now account for 77% of total artist revenues worldwide. This is as bad as the top 1% of earners in the world, who currently own 48% of global wealth – it is set to go up to 54% by 2020. Whilst such heavyweights are able to sell record upon record – just as some rich people keep getting richer – it is those in the middle who are squeezed the most. It is far from the truth to say that artists like these are damaging the music industry, like the top 1% of economic earners who dominate control of the world’s resources. These artists are propping it up. However, performers such as Adele, by doing so well, do create the momentary illusion that the music industry is in a healthy state. It isn’t.

But why is this? Much of it is due to the internet. In a broad sense, we now live in a generation of convenience, not conscience. If one can get something online more easily, then, for the most part, one will. The creation of websites such as Napster and Limewire, where files could be shared illegally online, made it far easier for the consumer to get the music they wanted without paying. All the music you want, for free, with no catch – apart from poor sound quality, which many were willing to overlook. The ways in which artists make money through music are fairly limited – they sell records (of which only a fraction of the revenue goes to the artist), or they go on tour. Of course, whether or not a record label chooses to send an artist on tour will depend (in part) on how many records they sell. No interest, no records, no tour – it is as simple as that. In these tough times, most major record labels won’t wait around to develop an artist and or to see whether or not sales pick up. Call it cruel – but their hands are tied. Sadly, they don’t have the funds or the time. This means that musicians who are more experimental don’t ‘make it’ into the mainstream the same way that they used to: and people wonder why the top 40 is so homogenous? Pink Floyd changed what it meant to make pop music in the 60s; David Bowie escaped the boundaries of genre in the 70s: both were commercially successful. Nowadays, the same sure bets dominate the charts year on year, because the labels, understandably, are afraid of taking risks at a loss. Thus the vicious cycle continues.

Newer, less traditional methods of making money are now becoming more common, with artists selling merchandise, fashion lines, or perfume in a bid to stay afloat. But it is only the Beyoncés, Britneys, and Lady Gagas of this world who can live this way – they are brands in and of themselves, and music is very much their secondary source of income. Their millions of dollars earned each year will not come from album sales, but from advertisement campaigns. Furthermore, many of the richest artists became successful before most of the illegal file-sharing sites were really a problem. Gossip magazines plastering their pages with pictures of mansions owned by The Rolling Stones, Madonna, and Prince do not help this image – those houses were bought with 20th century money. 90% of musicians in the UK make a measly £9000 a year.

Of course, the unmusical suits that started off this process do not suffer the consequences of what they have done. Sean Parker, the founder of Napster, is now worth $2.5 billion. An astronomically unfair reward for, effectively, killing off part of the soul of the music business. Napster’s dominance has now receded, in favour of more ‘moral’ counterparts, like Spotify and iTunes. However, these streaming sites have a dark side too. Spotify only pays labels and publishers between $0.006 and $0.0084 per stream, let alone what infinitesimal amount of this percentage goes to the artist. Statistics such as these have led pop stars like Taylor Swift (and Adele, with 25), quite rightly, to bravely withdraw their music from Spotify. iTunes fares slightly better, with artists getting around a 10% cut of every song, though Apple still interferes and keeps around a third of the profits to bolster its own empire.

Perhaps the saddest effect of this change in consumer culture is that it has altered the way in which people listen to music. Rather than hearing about bands through word of mouth, spending time in record shops talking to the owner, and carefully choosing an album, people spend hours scrolling through Spotify whilst updating their Instagram posts. It is that age-old idea of when something is easy to get, it is valued less. Whilst we certainly hear more music than we used to, it has all become background music: we hear without listening. Whilst 25 might break records on the billboard charts, you won’t see excited listeners queueing outside in the pouring rain through the night, discussing who they think Adele’s foremost influence is: Phil Spector or Bob Dylan.

Perhaps I am just being nostalgic. Maybe this is all progress, and I am a grumpy old fart who wants to go back to the ‘good old days.’ I’m not so sure. Call me old-fashioned, but with all this convenience, I feel that somewhere down the line, something vital has been lost. Whilst music making should not be about the pursuit of fame and money, fair reward for ideas is, I think, a fair request.