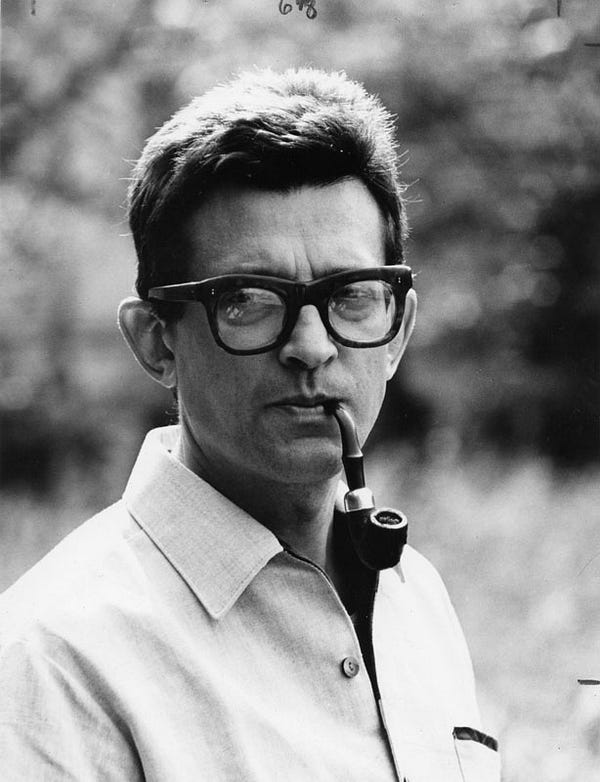

NICK MASTRINI looks at the work of Vojtěch Jasný, a key filmmaker in the development of the Czech New Wave movement and the subject of a major retrospective at the Czech Centre’s Made in Prague Film Festival.

Discovering the work of Vojtěch Jasný sheds light on the vital influence he and his contemporaries had on European cinema, and the importance of their films in response to the Communist regime. In the 1950s and 60s, the Czech New Wave, developing in parallel to the French Nouvelle Vague, saw filmmakers reinvent the rules of cinema, allowing for greater freedom of expression through the medium — and, importantly, conflict with Soviet ideologies.

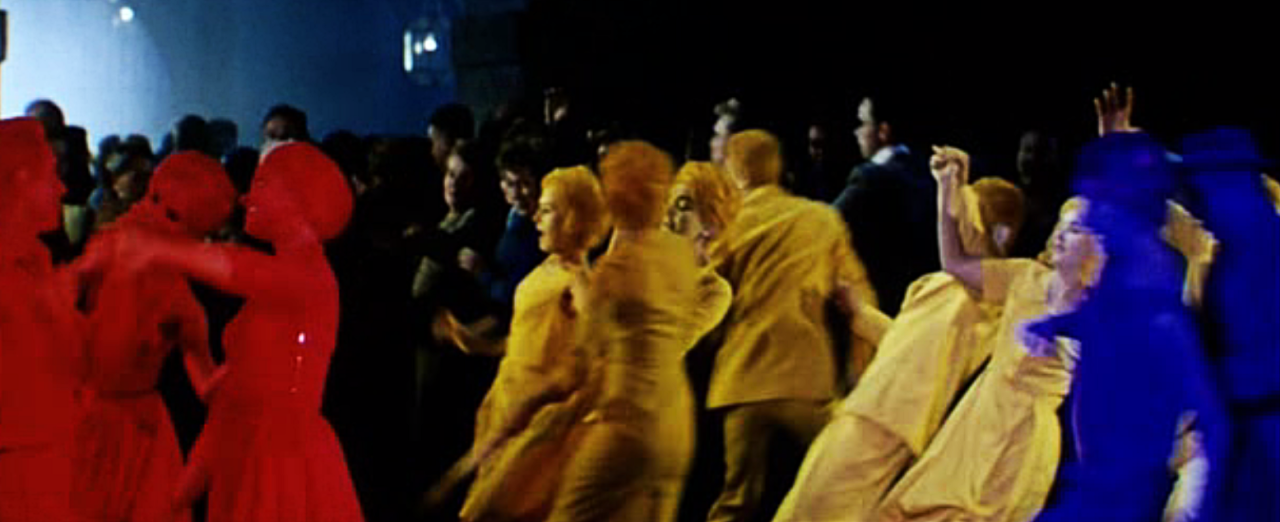

It was fitting for the Czech Centre to screen Až Přijde Kocour (When the Cat Comes) at Regent Street Cinema, where the Lumière brothers, inventors of cinema, showcased moving images on British land for the first time. Jasný’s 1963 Cannes award-winning film displays technical innovation suitable for the historic venue, in an allegorical tale of how a community responds hysterically to their true colours being publicly revealed. Cinematographer Jaroslav Kučera, who collaborated later with Jasný on his 1968 magnum opus Všichni Dobří Rodáci (All My Good Countrymen), presents these colours literally, as characters become vivid red, purple, and yellow.

This is all thanks to a magical cat with sunglasses, of course. Arriving with a travelling circus to a tranquil Czech town, the cat’s gaze, once these glasses are removed, reduces everyone to their fundamental emotion or characteristic: those in love glow bright red; liars purple; the unfaithful turn ‘yellow as brimstone, egg yolk, and canaries’. Kučera, husband of prominent New Wave director Věra Chytilová, visualizes this beautifully, showcasing the experimental photography that would make Chytilová’s Sedmikrásky (Daisies) a delight three years later.

Surely influenced by the work of French directors such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut in previous years, the fragmented editing and use of colour by Kučera allows Jasný’s film to be both playful while retaining its allegorical purpose. With a dry, innately Czech, wit, Jasný addresses how a Communist regime diminished the country’s complex personality to a rudimentary lifestyle, where citizens were judged and manipulated for pragmatic purposes.

Jasný and Kučera’s collaborations are lyrical in their visual storytelling, as seen in their 1958 film Touha (Desire), which exhibits the beauty of the Moravian landscape that would later provide the basis for the resolute drama of All My Good Countrymen. Jasný’s intimate knowledge of the Czech landscape and spirit, expertly translated into cinema, provided the precedent for filmmakers such as Miloš Forman and Jiří Menzel to extend the New Wave to worldwide acclaim and influence. In the face of censorship and oppression, Czech culture remained resolute, so that when, in 1968, apparent Communist ‘allies’ invaded the country to prevent reform, figures such as Forman, Milan Kundera, and Václav Havel continued to dissent through artistic means. While the Nouvelle Vague may be famed for its technical ingenuity and influence, the simultaneous creativity of these Czech figures, who infused their art with a firm political stance, should be noted for its significance to the development of western European cinema.

As 1968 approached, Jasný’s films became more grave and politically active, culminating in Countrymen, a script that took 10 years to complete and which was explicit enough in its criticism of Communism to be banned following the Prague Spring. Retrospectively, When the Cat Comes shows a childlike innocence when it refers to the political context of its creation, produced with more freedom for irreverence before the invasion of ‘68. In the guise of a fairytale, the allegory echoes Czech folk tradition, while suggesting the hysteria caused when an ideology is forced upon a community — adults panic while children play, as Jasný perhaps laments the loss of fundamental Czech values at the hands of Soviet powers.

Today, Jasný’s films should be viewed to discover how, despite political oppression, cinematic creativity can endure and have an international influence.