MIRIAM ZEGHLACHE asks why Dante’s perception of sin in his Divine Comedy still resonates 700 years after his death.

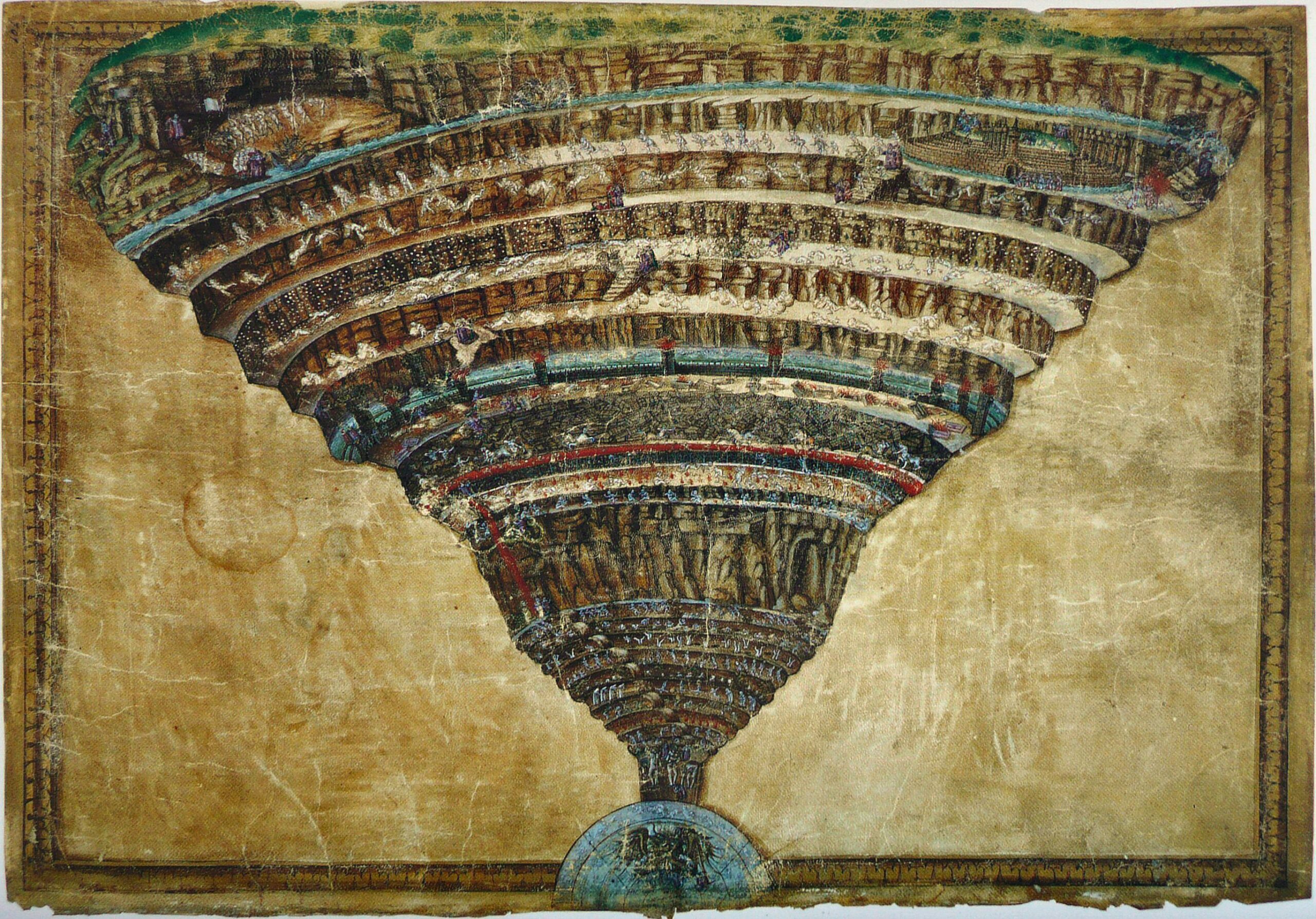

Dante Alighieri imagines in his Inferno (the first part of his epic the Divine Comedy) that he is entering the nine circles of hell with the ghost of the Roman poet Virgil. The closer the circles are to Satan’s pit at the bottom of hell, the more horrific they are, because of the severity of the spirits’ sins.

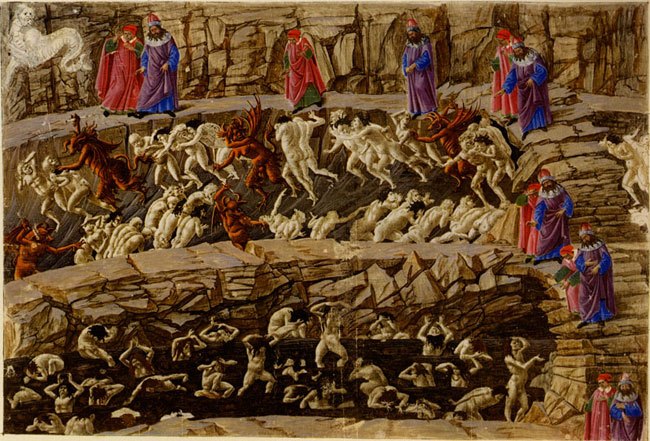

Let us set the scene: Dante is entering hell’s circle of the ‘lustful’ with Virgil. Although from the start, his depiction of hell is unsettling to say the least, this scene in particular is absolutely hellish. The place echoes with the screams of tormented spirits, since hell’s ceaseless wind ‘chafes them – rolling, clashing – grievously.’ Having allowed themselves to be swept up by the passions and desires they felt on earth (and in many cases were killed by), these sinners are accordingly swept up by hell’s ferocious winds. Among these souls, which include Cleopatra and Helen of Troy among others, two in particular catch Dante’s eye. The couple in question drift towards him; they are the 13th-century lovers Paolo Malatesta and Francesca Da Rimini, who were both murdered by Francesca’s husband when he caught them together, and are now doomed for eternity. Francesca recounts her first kiss with Paolo, and their subsequent affair. Dante, being a man of his time, judges the couple so harshly that he condemns them to eternal damnation; their love is perceived as a sin worthy of such a punishment. Despite his harsh judgement, however, he does not admonish them; he still pities them and weeps for their suffering. In fact, Dante’s empathy for the sinners is so extreme that he actually collapses, claiming:

[I] fainted away as though I were to die

And now I fell as bodies fall, for dead.

The couple’s doom is so terrible that it not only makes Dante emotional, but almost kills him; his empathy is so strong that he himself feels like one of the sinners he has condemned. In fact, Dante often reacts in this way during the course of his epic.

Why then did Dante place the lovers in hell? If he had the capacity to empathise to this extent, why did he even depict a hell at all?

Throughout the poem, Dante is very much influenced by the societal norms of his time, since he is remarkably broad in his definition of ‘sin’. Writing in Late Medieval Italy, Dante would have been constricted by societal norms, which were greatly influenced by the power of the Church, and dictated the delineations between right and wrong. Among the milieu of ‘sinners’, we find corrupt officials, authoritarian leaders, murderers and thieves. However, in their midst there are also those who have committed suicide, along with people of other religions, creeds and sexualities – people who, at least from a secular 21st-century perspective, have done nothing worthy of punishment. The ‘Forest of Suicides’, located in the sub-ring of ‘violence against the self’ is especially horrific; its inmates are transformed into trees, whose limbs are perpetually hacked off to the sound of their helpless screams for the ‘crime’ of having destroyed a life that was not their own to take. In other circles of hell people of other religions, most notably Islam, are tortured in nightmarish ways; the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and the Muslim general Saladin are included in Dante’s nine circles of hell. Classed alongside those of other faiths is the perceived ‘sin’ of loving whom one chooses, which is presented to us not only through adulterous sinners (such as Paolo and Francesca) but also through the depiction of the ‘sodomites’, a Renaissance term for homosexuals, whose very existence was considered sacrilege. Ironically, these people are punished under a Christian God, perceived to be the very embodiment of mercy. All of these perceived ‘sins’ have one thing in common; they are considered crimes against authority, be it that of state or that of the Church. These two powers in Middle Ages and Renaissance Italy were to all accounts synonymous, even in the City States that were not under the direct power of the Pope, like Florence. Even today, the two are not completely delineated, since the Vatican still holds an enormous amount of influence in matters of state and public opinion. Thus the inability to conform to the status-quo is a sin; to love whom one chooses and to think with one’s own mind is something that sets a person apart from society and renders them ‘other.’

Dante, however, has more than enough reason to count himself among one of the ‘sinners’ he encounters in hell. Though he fiercely judges Paolo and Francesca, he himself was in love with a married woman, Beatrice Portinari, whom he idealised to the point of deification in his Paradiso. Indeed, he was most certainly not a detached observer. 18 years before the completion of the Divine Comedy, Dante had been exiled from Florence by a sub-faction of the political group the ‘Guelfs’, the so-called ‘black Guelfs’, who opposed his own faction, the ‘white Guelfs’. His complete hatred for the people who banished him from his home is startlingly vivid; when met with Filippo Argenti, a political rival involved in his exile, in the River Styx in Canto 8, Dante actually asks Virgil whether they could stop for longer simply for the pleasure of watching him suffer:

Sir, this I should really like

before we make our way beyond this lake

to see him dabbled in the minestrone.

Therefore, Dante at once embodies the human – which renders him the equal of the ‘sinners’ he sees through his ability to empathise or hate them – as well as the cold, detached conformist.

I remember a couple of years ago seeing graffiti on a wall in Ravenna, Dante’s final resting place, with the writing, ‘Dov’é adesso Dante?’ (‘Where is Dante now?’). Good question. According to his standards, would he be residing among the obedient, conformist ‘good’ in heaven, or the ‘evil’ in hell?

Dante in many ways embodies two facets of humanity; that which expresses non-conformist empathy as well as anger, and the other, aloof facet which complies with the often combined status-quo of state and church and its definition of ‘sin’ as the embodiment of non-conformism. The former facet is conveyed to us even through the mere description of Dante’s distress when he sees the suffering sinners, because in that small action, he is throwing into question the validity of their alleged ‘sin.’ As a proto-Renaissance writer, Dante does to some extent challenge the mostly undisputed definition of the ‘other’ by not only communicating with them, but also feeling their pain. Thus, we could interpret Dante’s Inferno as a depiction of the human psyche, because through Dante’s dual role, we may question the extent to which we choose to act as judge or remove ourselves from our self-appointed pedestals.

In other words, to what extent should we allow society to shape our concept of morality? The fact that this question is still crucial 700 years after Dante’s death is testament to its timelessness. By adopting the at once judgemental and aloof nature of Dante, we align ourselves to the status-quo in an effort to not be branded a ‘sinner’, or in this case, ‘other.’ In 2021 as in 1321, this concept is still very much relevant not only in attitudes towards oppression, whether it be based on race, class, sexuality, gender and many other forms, but also in the way oppression is upheld by the status-quo in almost every institution. The creation of the ‘sinner’ or ‘other’ allows for an easy scapegoat to oppress and vilify, a concept that is often entrenched within the mind of the 21st-century individual, let alone that of the 14th-century. It is only by breaking the bonds of this entrenched mentality that, as Dante shows, one is able to think and feel as an individual rather than as an institution.

These oppressive chains can only be broken, however, if further, active steps are taken; it is not enough to passively empathise with tears when faced with injustice as Dante does. Spectatorship, empathetic or otherwise, only serves to perpetrate this dangerous concept of ‘us’ and ‘them’, or ‘good’ and ‘evil.’ Would Dante the non-conformist, as opposed to Dante the conformist, have ever considered taking these steps? I suppose it is only left to his readers to decide.

Featured Image source: wikipedia.org