HANNAH BEER discusses Loral Amir and Gigi Ben Artzi’s new film and photographic series, Downtown Divas.

Back in the 90s when scrawny 14 year old Kate Moss was catapulted onto catwalks, billboards and front covers for the very first time, she spawned one of the most controversial (and thus one of the most adored) movements in fashion: Heroin Chic. Responsible for the rise of kohl eye liner, Size Zero, and the fall of Cindy Crawford as America’s Top Model, Heroin Chic has had one of the most prolific and lasting effects of any trend that any industry has ever seen. And whilst it never really went away, it is now, just like Polaroid cameras, scrunchies and everything else 90s-related, undisputedly back ‘in’.

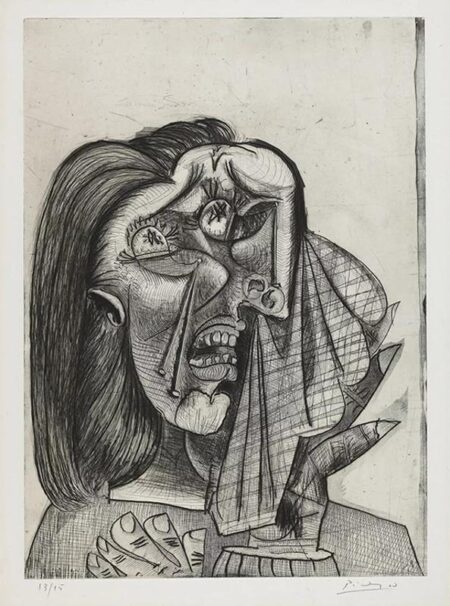

As is inevitable when something is ‘in’, Heroin Chic is once more being commented on, questioned and protested against. The responses aren’t entirely different to those incurred 20 years ago, but amongst all of the predictable “it’s turning our teenagers into addicts” rubbish (let’s be honest, eye liner just can’t do that), there was one comment on the movement that really caught my eye: that of Loral Amir and Gigi Ben Artzi. The artists have made ‘Downtown Divas’, a 16mm short film and photograph series of several Russian heroin addicts, many of them prostitutes, wearing designer clothes. The idea in itself is uncomfortable and the pictures and film even more so. In an interview with Bullett Media, Amir and Artzi said their aim was to ‘highlight reality’, which they certainly do: the film is, undeniably, very moving. They get the women to talk about their dreams, their upbringing, their relationships; they avoid asking about drugs but they’re brought in nonetheless. The pictures succeed in making you feel the absurdity of the label ‘Heroin Chic’ and the sometime self-indulgence of the fashion industry. But beyond this, both the film and the photos made me question something else. All the while I was watching the film, the only thing I could think was: what happened to the women afterwards? Amir and Artzi told of the danger surrounding the bridge that they found these women under, of how the women asked them explicitly not to say which city they were from – did they just send them back to this bridge? Let them play dress up for a day and then push them out of the shiny world of designer clothes and artists’ studios and ‘chic’, back to heroin and their own cold, hard, ‘reality’?

Sadly, it would seem that this is exactly what happened. They paid the girls and that was it. In their interview with Bullett, they talked about how ‘mentally exhausting’ and ‘painful’ the process was for them; how they had difficulty sleeping for a while afterwards. But reading the interview and seeing the final product, I couldn’t help but feel that the artists seemed almost completely detached from the women they were shooting. It felt, in all honesty, like they were using the women to make a point rather than making a point to help the women.

And so, here comes the eternal question: can art ever be just for art’s sake, or does it have some sort of moral responsibility towards its subject matter? There’s a part of me that wants to disagree with the latter and maintain that art exists in a realm of its own; that it has no responsibility other than that to itself. The practical side of me is, in this instance, shouting that that’s bollocks. The truth of the matter is that Amir and Artzi’s ‘Downtown Divas’ made me uncomfortable for all the wrong reasons. Yes, it made me feel a little ashamed for sometimes purposely emphasising the dark circles under my eyes in pursuit of that Kate Moss by Corinne Day look, but more than that, it made me feel the enormous hypocrisy of art like this – the sort that criticises one thing’s insincerity by being equally as contrived. The artists wanted to ‘highlight reality’, but all they did was highlight it for their audience. To them, the troubles and the lives of the women interviewed are just the subject of their work: something that shocks, maybe even motivates other people, but not them.

Art designed to shock, and shock only, has been around forever, and there’s nothing wrong with it. We love it because we love to be shocked, challenged and called to account, especially by something that usually can’t be called to account itself. But art surely loses that privilege when it uses the sadness, messiness and complexity of real people to this end only. Doesn’t it become, at this point, something nastier than art; something closer to selfish and sadistic than moving or inspiring? ‘Downtown Divas’ is meant to confront us with the reality of what the artists call ‘society’s own product’, and it does. It’s just that the product in question isn’t prostitution, or addiction, or the glamorisation of either of these: it’s the pursuit of controversy. And what a frightening product that is.