HELENA WACKO explores the juxtaposition of aesthetics and crude reality in the work of photographer Mandy Barker.

Every now and again, an image of sea turtles choking on plastic bags or polystyrene trash littered across shores complements headlines on the growing plastic pollution in our oceans. These unpleasant images have become commonplace to the general public. They are perhaps granted a brief concern by onlookers, but rarely a second look. Mandy Barker’s artwork greatly contrasts this salient indifference which plagues the comfortless images. She has devoted her career to photographing discarded litter from oceans collected from around the globe, ranging from the British shores to Hong Kong beaches. Her photographs are akin to celestial constellations. Plastic debris, which are the principal subjects of her images, are laid out to mimic the faraway asteroids mapped out onto our night skies. Her work, much like the cosmos, are a carefully organised chaos. She places the plastic pollutants in oceans into a new context. By coordinating throwaway objects, such as bottle caps or plastic cups, within an artistic framework, these items which were once categorised as waste are imbued with an aesthetic value. This aesthetic attraction of Barker’s work contradicts the stark ugliness of the issue at hand. With this juxtaposition, Barker’s work compels a new attentiveness to plastic pollution. Her art can be viewed as a remedy to the desensitised attitude towards the shocking reality of the problem.

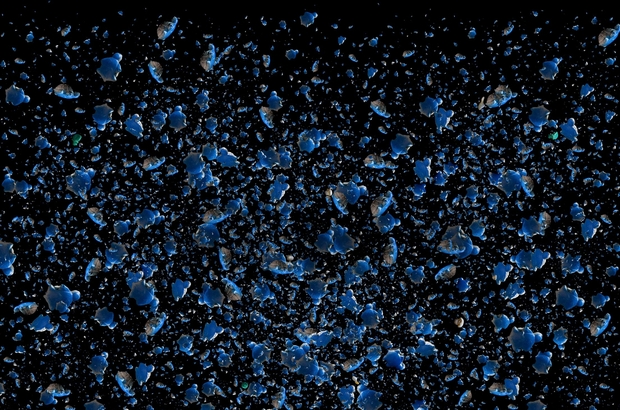

The photographic projects Barker has created using various plastic debris objects addresses a range of topics. For example, SHOAL depicts the rising levels of marine plastic in the Pacific Ocean due to the Japanese Tsunami in 2011. Another artwork, PENALTY, focuses on the football as a single plastic object washed up onto beaches around the world. Despite the differences in subject, her various projects share a similar pattern of experimenting with space, illusion of dimension, and colours in relation to waste. Generally, the debris is depicted against a black negative space, generating a feel of vastness and emulating the deep sea it was recovered from.

The image Refused, a part of the larger SOUP series is a prime example of this. The image displays plastics in intense colours against the quintessential black negative space. Refused possesses a particular in depth quality through the composition of the debris; larger items concentrated in the foreground of the frame against smaller pieces layered throughout the photograph. Barker keeps the image busy with smaller scattered items, primarily bottle caps. Meanwhile, larger items are singled out through sheer size. For example, a toothpaste tube is enlarged, prominently dominating the disorderly background. Barker creates various focal points amongst what initially appears a chaotic composition. Once the viewer realises these enlarged, focal objects, it is evident that all the objects share a common characteristic: teeth marks. Each one of the plastic pieces have been affected by chewing, indicating that they have been ingested by animals. The toothpaste is particularly emblematic of this, with its inferior section contorted in a way that suggests that it had been consumed, and rejected from the body. Colours are visibly eroded, perhaps through stomach acid. Bite marks are embedded onto the surface of the tube. This motif of teeth produces an irony with the presence of the toothpaste. This recurring motif can be connected back to the larger significance of the photographs title: Refused. After all, these items were only attempted to be ingested by animals then rejected precisely because they do not belong in the sea, even less so within animal intestines.

Barker’s environmental commentary becomes apparent and stimulates an emotional reaction in the viewer. By displacing the consumed plastic from the context of graphic images of animals, she draws in people to question what the plastic debris are. The viewer, through a process of recognising the signifiers of eating, is shocked that such an object would ever be consumed. Barker makes plastic shocking again by displacing it. She re-contextualises plastic debris into the frame of art with an aesthetic intention. Refused is an artistic statement that links to the central issue plastic pollution produces in the sea: its detrimental effects on animals.

Marine life is the primary victim of the environmental catastrophe. Animals are continuously entangled and ultimately suffocated by plastic matter. They are physically asphyxiated by small strings of plastic, and poisoned by its toxicity. Plastic debris suspended in the ocean can also have a starving effect on marine life. It fills their stomachs and becomes permanently ingrained into the ocean’s food chain – and eventually into ours. Human bodies are gradually becoming polluted with Microplastics; our food is contaminated by our own waste. In Barker’s artworks, Refused makes reference to attempted ingestion, and the larger SOUP series touches on the death of sea creatures due to the large accumulation of plastic debris. Where the artworks only cites the deleterious effects of pollution, the real statics behind Barker’s art are disturbing. Over 100,000 marine creatures a year die from plastic entanglement alone, and these are only the ones physically documented. This statistic does not include death due to plastic ingestion or the one million seabirds that die yearly due to plastic pollution. Our use of plastic inevitably circulates into important marine ecosystems- we must hold ourselves accountable. Gradually, our bodies will also suffer as a consequence.

Ultimately, a comparison can be drawn between how Barker immortalises plastic debris in her various photographic projects to how the slow material degradation of these items are equally as permanent. Plastic particles can endure up to 500 years of atrophy. This recurring subject of permanence in Barker’s work applies to several aspects of the issue, not only the endurance of plastics and its toxins in the ocean, but also the long lasting effect it has on Earth. Have we already passed a point of no return? In other words, is this damage already permanent? This is the uncomfortable truth underlying the initial aesthetic of Barker’s work. Perhaps it is this very juxtaposition of visual beauty and the ugliness of reality that can evoke individual action on par with the scope of the environmental issue that is plastic pollution.

Featured image: SOUP: Turtle, Mandy Barker, 2012. Ingredients; plastic turtles that have circled & existed in the North Pacific Gyre for 16 years, as a result of a shipping container carrying over 28,000 childrens’ bath toys washed overboard on 10 January 1992. Additives; ducks, beavers & frogs. Image credit: Mandy Barker, 2012.

This article is published in our Environment in Arts series, raising environmental awareness in advance of UCL Climate Action Society’s Sustainability Symposium that took place on the 16th November.