ALASTAIR CURTIS reviews Yanagihara’s A Little Life, nominated for the Man Booker.

A Little Life was the best book of 2015.

Hanya Yanagihara, when talking about A Little Life, her second novel – and the second to be published in as many years – suggests she ‘wanted everything turned up a little too high’. All the elemental feelings of a Greek tragedy are here – the suffering, the cruelty, the passion – but inculcated as if with a pipette, and left to burn slowly in a series of quiet reactions across the book’s 720-odd pages. As it moves through happiness, depression, and eventually grief, her writing, though vivid, is characterised by restraint, never once seeming overwrought or melodramatic.

The same can’t be said of her critics. The brouhaha surrounding A Little Life has been tremendous. The novel has been nominated for half a dozen prizes, won several more, and was controversially pipped to this year’s Man Booker by another doorstop of a novel, Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings. It’s been hailed as a ‘masterwork’, a ‘tour de force’ and the work of ‘a major American novelist’, in reviews awash with tears. And the tears – frequent, always profuse – stand as testament to the empathy Yanagihara’s writing tends to elicit. On more than one occasion, I wanted to swish my hand about in the novel and scoop the characters out, dripping – soaked to the skin in suffering – but safe.

With broad strokes, Yanagihara sketches the lives of four talented New England college graduates, arriving in the Big Apple fresh-faced and ambitious at the novel’s start. Success follows, failure too, and at one point, Malcolm, one of the graduates, speaks for all of four of them when he concludes: ‘his work (at a standstill), his love life (nonexistent), his sexuality (unresolved), his future (uncertain)’. But the years roll by, Yanagihara sees them into their thirties, and they join the ranks of the metropolis’ brightest and best: Willem becomes a film actor; Malcolm, an innovative architect; JB, an artist, and Jude, an impressive corporate litigator. Yanagihara elides months, years; contours fill out into characters, characters into people.

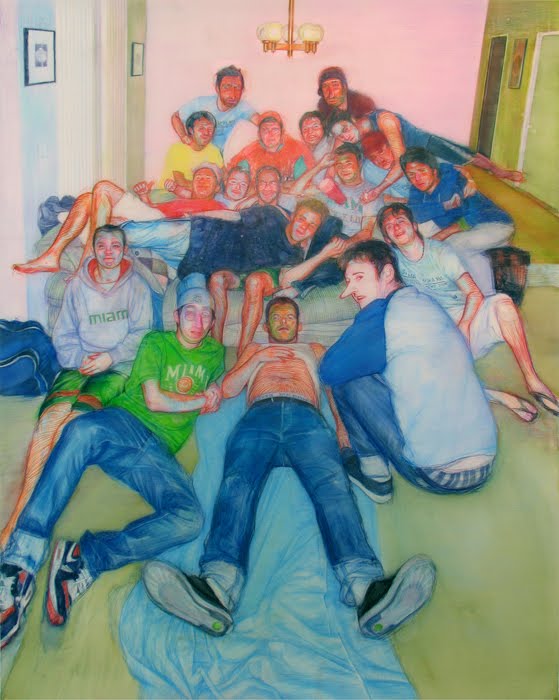

As if with tunnel vision, Yanagihara limits the narrative to this quartet, a so-called ‘bunch of Peter Pans’: Willem, Malcolm, JB, Jude. The four men make up a society as hermetic as the fictive, isolated Micronesian tribe Yanagihara describes in her first novel, The People in The Trees. The novel celebrates this intimacy even as it perplexes, and occasionally upsets, those around them. And as it endures into middle age, their friendship becomes as an appealing alternative to the pressure for marriage and kids. Their parents, friends, even partners, are pushed off into the novel’s periphery. Over the decades, Willem’s relationships with various women collapse, but his friendship with Jude intensifies: the bond they share – exceptionally close, tender and passionate – evolving into a Platonic relationship.

In interviews Yanagihara has complained about the ‘small emotional palette’ male characters are given in mainstream literary fiction. Men – in books and out of them – often lack the language and support networks that allow women to describe, and so ease, feelings of vulnerability and anxiety. A Little Life goes some way in providing a corrective because of the intense male friendship it depicts – even if this results in a marked absence of female characters. Yanagihara has often cited the art of Geoffrey Chadsey as an influence. The four friends in A Little Life are drawn from the men in Chadsey’s work, where they vaunt a reckless confidence: uninhibited, loud, but, crucially, emotionally and physical intimate with one another.

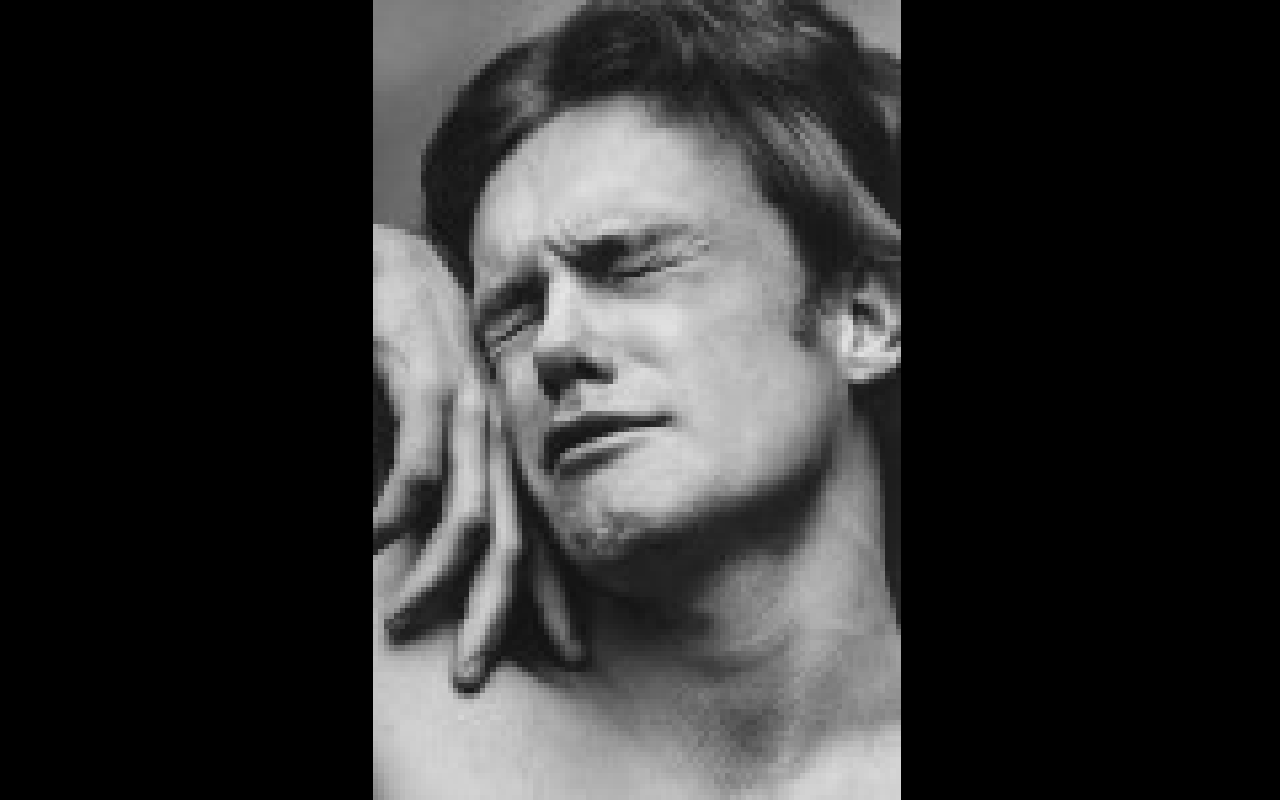

This intimacy, at least in part, comes from their mutual desire to protect Jude: a tortured individual, bearing mysterious chronic injuries. Jude is anxious about his appearance, about intimacy, and about the happiness (albeit rare) he enjoys. He can’t bear to have people looking at his body, can’t bear to look at himself. The others struggle to work him out, with JB calling him ‘the postman’: ‘post-sexual’, ‘post-racial’, ‘post-identity’, and ‘post-past’. Though irritated by this secrecy, his friends care for him no questions asked – but the reader’s curiosity is piqued, and the novel’s focus settles on Jude with the promise of answers. It’s then that A Little Life takes an unexpectedly dark turn and the book’s content aligns itself with the photo – a man’s face twisted in pain, by Peter Hujar – on its front-cover.

Yanagihara has described the emotional trajectory of A Little Life as like an ombré fabric: one colour bleeding into another, the hue darkening by steady increment. She erodes Jude’s secrecy in the same way: with a drip drip of information, unearthing his childhood in piecemeal flashbacks that are as disturbing as they are compelling.

Abandoned by his parents in a dumpster, Jude washes up at a monastery, where for years he suffers physical and sexual abuse at the hands of the monks, doctors, and later his counsellors: a cycle of unspeakable evil broken only when one of his abusers runs him over with a car, leaving him physically, and emotionally, crippled. Jude’s daily, lonely crusade is to prevent this awful past from leaking into his new life (‘how much time he actually spent controlling his memories; how much concentration it took’). He dams it up, anchoring himself in his successful legal career, but his suffering nevertheless reverberates down the years, provoking successive waves of humiliation, fear and shame.

Jude’s self-loathing manifests itself in self-harm. It occurs most nights: he cuts his forearms, biceps and thighs with a ferocious resolve, criss-crossing over old cuts for lack of fresh skin. His injured legs worsen, unleashing spasmodic pain; the scars on his back, an irreducible crust (’as glossy and taut as a roasted duck’). It’s a routine show of horror that possesses an extraordinary, lurid power: Jude’s arm ‘had grown a mouth and was vomiting blood from it, and with such avidity that it was forming little frothy bubbles that popped and spat as if in excitement’. Yanagihara’s imagery is direct, never shy, but it’s at its most impressive when it’s subtle, as when Jude’s anguish is symbolised by the pack of ‘hyenas’ (with ‘snapping, foaming jaws’) that rattle about in his mind like a virus in a computer.

‘Books lie, they make things prettier’, Jude thinks. Not here: his daily suffering is so unremitting, a cycle of self-abuse realised with such unsparing meticulosity, that Yanagihara’s editor suggested it was ‘just too hard to take’. It very nearly is. But Jude’s story captivates because of our desire to see him delivered, finally, exhaustedly, to the happiness that has long escaped him. And in this, the novel alerts us to our own powerlessness as readers: we know, deep down, that happiness for Jude is never going to be as unproblematic as we’d like it to be, but we want – pray even – for A Little Life to prove us wrong.

At times it feels like it will. Jude has a circle of friends who are completely, selflessly devoted to him: Willem of course, JB and Malcolm too, but there’s also his doctor-friend, Andy, and Harold, Jude’s law professor who, with his wife Julia, comes to adopt him. Their superhuman kindness becomes a counterpoint to the novel’s extreme cruelty. And when Jude and Willem take their long-talked of trip to Alhambra, in one of the novel’s tenderest moments, it seems everything may be coming up roses.

But every time his friends pull him back from the brink, Jude creeps towards it once more with a renewed determination. And an accumulation of bad luck – a one-time sadistic sexual partner, the death of his close friends – finally send Jude spiralling back into his past, from which his friends, for all their unending efforts, prove powerless to save him.

The novel’s lack of closure, of an easy sentimental conclusion, is consummate for a work that delivers such solemn truths: that kindness might not be enough to rescue someone intent on self-destruction; that people can suffer the direst cruelty without redemption; that we cannot, however hard we may try, escape our past. Jude’s life is indeed a little life: an exhausting existence lived out in the irrevocable shadow of his past. But Yanagihara gives him friends, family, Willem: a little light – and often that’s all we can ever hope for.