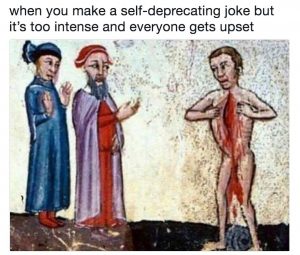

OLIVIA BOUZYK explores the intersection of memes and manuscript marginalia.

Memes are an all too relatable aspect of our everyday life in this hyper-visual internet age. They catch our eye as they pop up on our Facebook, Twitter or Instagram feeds; whether we have been tagged in one or not, memes are in our constant periphery, providing a humorous mode of communication amongst friends and followers. Whilst these images may combine Post-Modern theory with strange looking pets or Kermit the Frog, recently the medieval image has found its way into this digital territory. This intersection of the Medieval image and Modern communication is surprisingly not the most unlikely combination – in fact, it is a partnership that makes complete sense.

Facebook pages such as Classical Art Memes and Medieval Reactions appropriate the Medieval image and caption it with amusing (and painfully relevant) anecdotes; ‘Me at 8pm: “I’m only having a few and I’m deffo getting the last bus home”; Me, drunk at 5am in Maccies…’. The images have been torn off the manuscript page and inserted into a virtual sphere, making it somewhat hard for the modern viewer to appreciate the original context. The images in discussion here are manuscript illuminations that would have featured mainly in religious texts. These images were not deemed to be ‘art’. Art, as we think of the term today, did not exist within the context of the medieval period; instead, craft was considered the main visual form. Art and craft were interchangeable with life and worship. Just as the meme is not acknowledged as an important ‘high art’ form today, neither was the manuscript illumination.

The Medieval period is, to most, one of mystery. Frequently referred to as the Dark Ages or Middle Ages, the period approximately spans from the 5th to the 15th century. Whilst this period is often referred to as ‘backward’, this is not true. It was a time of great social change and turmoil. The Middle Ages in European history is largely ignored because it is sandwiched between two more academically fashionable periods: Roman civilization and the Renaissance, stages we might view as more ‘technologically advanced’. However, this revival of Medieval imagery in meme culture may counter this previously accepted view.

Regarding the visual culture of this period, the average person would not have seen many images in his or her normal day-to-day life. We, on the other hand, are so oversaturated with the visual that it aggressively confronts us wherever we go. For the Medieval viewer, images were only encountered within the space of the Church, and so they had highly religious resonances and connotations. The image held great power over the viewer and could influence the viewer’s mind, body and soul. Images could even affect the physical health of the viewer: pregnant women, for instance, were especially susceptible to the power of the image and were warned against the sight of monstrous images, as it could affect the wellbeing of their unborn child. The eyes were believed to be the gateway to the soul. The intensity with which the image was viewed is lost on a modern audience – even the unsightly images on cigarette packets seem to have no power in discouraging the smoker.

The images used by popular meme pages today would have originally engaged the viewer in not only a visual but a corporeal manner; it would have been a totalizing, synesthetic experience. The parchment manuscript page was made from stretched animal skin and thus had a distinctive touch; images were caressed, rubbed and kissed. The manuscript page choreographed the reader to engage all senses, something that can be compared to the virtual reality technologies of today. The Art Historian Michael Camille has commented on the similarity between the multi-sensory manuscript page and the interactive screen in emerging technologies in contemporary society. The touch screen makes us interact with images in a similar manner: just as the medieval viewer would have stroked the manuscript page, the modern viewer swipes the screen on his or her smartphone.

Through the appropriation of Medieval images in memes, readers are engaging with visual culture from over 1000 years ago. However vast this temporal distance may be, it is interesting to note that we still find these images as amusing as they were initially intended to be. The illumination usually provided a break from the text, acting almost as an advert on the margins of a newsfeed. The marginal images thus provided light entertainment for the reader, just like the easily digestible, relatable content of memes. Later in the Medieval period, the role of illuminator and writer was occupied by two separate people. In the production line of the manuscript, the illuminator would handle the page after the writer, allowing them the opportunity to play on the meaning of the words, making visual puns around the text. These images were largely crude, subversive and base, often juxtaposed with the serious religious nature of the writing. Interestingly, for the production line of memes, it is now the illumination that precedes the text, with caption acting as the space for subversive commentary.

Whilst Facebook and Instagram pages appropriate images from all periods in history, it is interesting to notice that the original reaction from a medieval viewer to an image in a manuscript can still have the same effect on a modern viewer. Whilst the illuminated image was marginal in its original function, being an addition to the main text, the meme too is marginal in its relation to what is considered ‘art’ today. These images reveal an engagement with humour that is inherent to both contemporary and medieval visual culture. The medieval image intersects with this modern visual culture, achieving similar responses from its audience across time.

Featured image courtesy of buzzfeed.net