ROSE GABBERTAS contemplates how the Covid-19 lockdown has affected the UK’s problematic relationship with food and food waste.

Scrolling past yet another banana bread photo on Instagram, it’s easy to feel cynical about the clichés of lockdown cooking that have exploded as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet the onslaught of sourdough starters that heralded the nation’s return to wholesome home-cooking signals a much more significant shift in the way Britons think and feel about food.

Long before Boris Johnson implemented a nationwide lockdown in late March, supermarket shelves across Britain were swept clean, having been emptied of essentials like toilet paper and pasta by a hysterical wave of panic-buyers. As a direct result of consumer stockpiling and compromised supply chains, many people experienced scarcity for the first time in their lives. Forced to stare at the hard reality that food is, in fact, finite, we began to value, respect and honour food in a way that has been lost since wartime Britain. Many of us reverted back to weekly or fortnightly shops, carefully constructing meal plans and adapting to create new meals out of leftover food. Research by Hubbub – a UK-based sustainability charity – found that 57% of Britons value food more now than they did pre-coronavirus, and as a result, levels of food waste between April and June fell significantly in the UK.

Ever since the American-influenced consumerist culture boom in the 1950s, the UK has fostered a problematic food culture. As a nation, we have learned to rely on endless choice and abundance, regardless of quality or season. The idea of always being able to have whatever we want, whenever we want, has given way to a shockingly throwaway food culture. Recent figures published by WRAP in January 2020 revealed that households in the UK throw away 4.5 million tonnes of food each year that could have been eaten, collectively worth £14 billion. In the UK alone, 24 million slices of bread (or one million loaves) are wasted every single day, which annually produces an amount of carbon dioxide equivalent to more than half a million return flights from London to New York. On top of this, prolonged austerity and rising poverty levels combined with increasingly busy work schedules and stressful lifestyles have generated a mass departure from home-cooking, with more and more households relying on take-out food or ready meals. In the space of just a few generations, an alarming pattern has begun to emerge in which the quality, nutrition and provenance of food is superseded by aesthetics, speed and convenience on a mass-scale.

However, the optimistic among us can see a silver lining to the pandemic in that it has helped us to see the true value of food. Many of those who have been furloughed or are working from home have enjoyed more time for cooking from scratch, partly necessitated by the closure of restaurants and pubs. Covid-19 has brought to light that not only is food a precious, limited commodity, but it also has an incredible emotional significance. Whilst the methodical, creative process of cooking can be a therapeutic time to slow down, the act of eating itself is one that is joyful, and has provided comfort for many over what has been a very stressful, uncertain and frightening time. During lockdown, a slower pace of life has lent crucial time to reflect on what is truly important in life, with sitting down and eating good food with loved ones high up on many people’s priorities.

Nationwide shortages of eggs, flour and sugar from March to May heralded a nostalgic return to home baking, as cooking simultaneously became a source of comfort and a rewarding source of entertainment that has the capacity to bring about a real sense of achievement. As a student, I’ve seen a number of friends get creative in the kitchen over lockdown, setting up dedicated Instagram accounts to document their culinary projects; beginner bakers soon grew to be focaccia aficionados and were relishing the challenge of more complex patisserie. My brother quickly became a gardening fanatic, using extra time saved from his two-hour daily commute to grow his own herbs and vegetables in the garden. This interest in sustainable, home-grown food is echoed in the sharp rise in applications for allotments across the UK during lockdown.

With cookery books and kitchen gadgets widely out of stock online, it’s clear that lockdown has incited a mass rediscovery of the joy of cooking. But as the world begins to slowly heave itself into recovery, the question remains – can we solve our relationship with food for good? Will we have time to bake bread and cook from scratch when we return back to work and university full-time? It’s easy to romanticise ‘the good old days’ of the early twentieth century, where Britons largely sat down every evening for a home-cooked meal made from local, seasonal ingredients. In today’s globalised world, food production and consumption are inherently different, but that doesn’t mean it has to be inherently worse. We must all take the responsibility of educating ourselves on how to be ethical and sustainable consumers, and make an active effort to carve out sacred time for both cooking and eating as lockdown eases further.

For all of us, the pandemic has been a life-changing period which has forced us to re-examine the way we live our lives. It’s impossible to know if society will ever fully return to its pre-Covid state, but over the last six months, many of us have made positive changes to the way we eat and perceive food. We still have a long way to go in terms of reducing the UK’s food waste, but the figures from lockdown are promising. The UK government’s plans for a so-called ‘green recovery’ from Covid-19 need a greater focus on food if we’re going to create a more sustainable society. Returning to a culture of home-cooking is a step in the right direction for repairing Britain’s relationship with food, not only in terms of food waste but also in battling the national obesity crisis. Relearning the intrinsic value of good food must be the springboard to address other issues we have with food and its production, including the threat to food standards imposed by an imminent US trade deal, and the detrimental effect that intensive animal farming has on ecosystems and climate. The next six to twelve months will reveal whether Britons can retain the lessons of this surreal and trying period, or whether we’ll swing back into old habits at the first given opportunity.

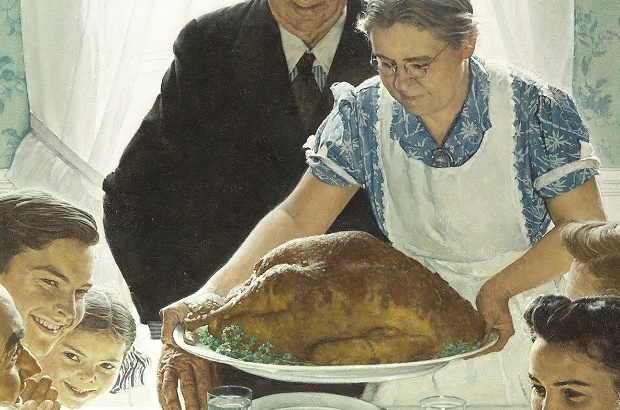

Featured image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum (www.nrm.org)