NICK MASTRINI explores the emotional connection between food and film.

What’s your favourite meal? Your choice might stem from tradition; the comfort of a Sunday roast with the family, or a soup your mum made when you were ill as a child. Often our favourite foods are based on a moment in time when our food has formed a perfect response to a need created by our mood. There’s something inherently cinematic about this nostalgia.

Eating your favourite meal is, in many ways, no different to watching your favourite film. Both are personal, sensory associative experiences, in which tastes and textures – like sights and sounds – trigger an emotional response. We eat a variety of foods and watch a range of films because, beyond the biological and social reasons for doing so, they are a tool through which we identify our partialities, a process which ultimately tailors your personality and makes you you.

This is the pleasure principle: in a bid to escape pain and stress, we seek moments of pleasure to imbue our lives with notes of sweetness that we commit to memory. Both food and films grant us this warmth of familiarity, whether the experience resonates with the past or perfectly mirrors the present. It’s fitting, then, that films frequently place food at their emotional core.

In Ratatouille (2007), the ageing, stubborn food critic Anton Ego’s favourite meal is… ratatouille. When he finally samples the dish at the film’s climax, its taste is so simple and yet so tied up in tradition, that he is instantly transported back to his childhood. This flashback reveals the joy Anton so heavily associates with his mother’s cooking. The pleasure principle is rooted in the ‘id’ – the instinctive part of our minds that seeks gratification. When Anton drops his pen in response to the taste, it signifies a return to his childlike instinct, his veil of criticism – his ‘Ego’ – having shrouded his initial passion for food.

Food critic, Jay Rayner, recently shared a similar sentiment, noting that ‘even today, buttery eggs make [him] think of the … tone of [his] mother’s voice.’ In the twenty-first century, this process of reflective association feels especially common; the spheres of both the culinary and the cinematic have a retrospective tendency to them. This is partly because these experiences, once highly social, have become more attuned to the needs of the individual as opposed to the group. As we increasingly ‘lack time’ to eat together, and modern technology allow us to watch movies alone, cheaply and easily, the nostalgia related to food and film becomes more and more acute.

While Ratatouille epitomises the way in which an individual often makes personal connections to traditional meals, the social aspect of dining is crucial to many films. The dinner table, diner booth or café corner allows for concentrated dialogue between characters sat face-to-face, in turn reminding viewers that crucial moments in our lives often unfold during shared meals. Take any Quentin Tarantino film, through which the table becomes a realm of tension and curiosity, around which characters plot robberies and heists over a strudel or a coffee. Here, the proceedings are at odds with the pleasure of the food, creating a tension within the narrative.

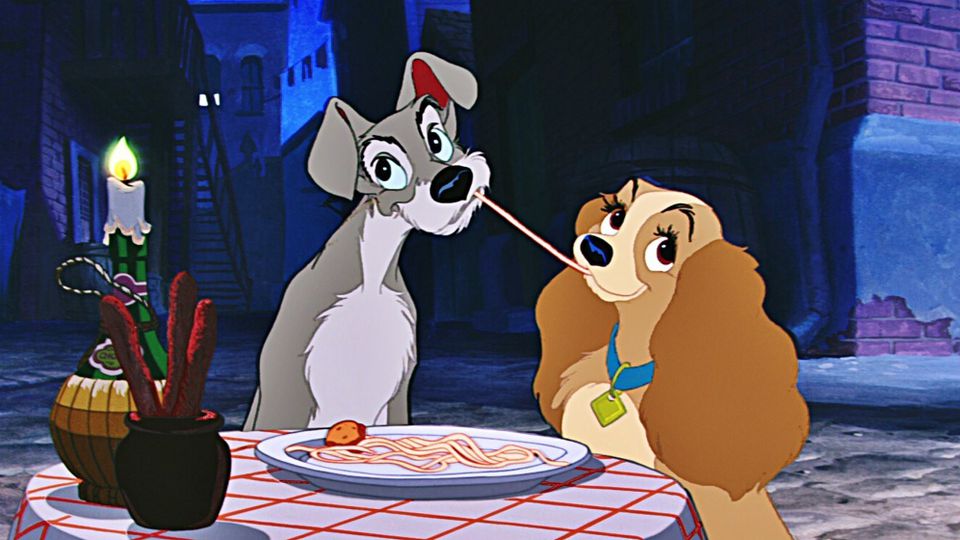

Alternatively, films can use the pleasure of food to stimulate a sense of harmony between characters sat at the dinner table. The famous scene in Lady and the Tramp (1955), in which the pooches smooch whilst sharing a plate of spaghetti, reminds us of the unifying potential of food. On a less sentimental note, in When Harry Met Sally (1989), the narrative’s climactic scene (if you will) takes place in Katz’s Deli and what is initially a mundane conversation becomes defined by the public nature of their location, as love and food intertwine and we are presented with the memorable line: ‘I’ll have what she’s having.’

More recent films emphasise the importance of community in relation to food. Both Chef (2014) and The Hundred-Foot Journey (2014) portray shared experiences of food as a means for meaningful human connection. A group may participate in the same meal, whilst making their own personal range of associations with the food on offer. In The Trip To Italy (2014), this balance between the social and the individual is made clear as Rob Brydon and Steve Coogan discuss their lives over a series of meals, discovering more about both each other and themselves.

What connects these films is a sense that shared dining allows food to be more than just an essential part of life. The meal as a social experience, especially in this digital age, stimulates the things that give our lives meaning: the memories we create with the people we love. As we seek to make each day unique from the last, both great movies and delicious meals provide us with the sensory pleasures that form the fabric of our personal histories.

An article entitled ‘Food on Film’ would be incomplete without a video montage celebrating some of film’s finest dining moments. You can view the video that accompanies this article on the SAVAGE YouTube channel.