COLETTE ALLEN discusses the complicated nature of Playboy’s interaction with the Civil Rights Movement, and what this interaction said about American society at the time.

In the Editor’s Note of the first issue of Playboy, Hugh Hefner characterised his expectations of a typical reader as the kind of guy who invites a female acquaintance in for some cocktails, music, and “a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, and sex.” I read this and roll my eyes at how often I’ve had that exact ‘quiet discussion’. You knew them too well, Hef.

In his long life Hugh Hefner successfully manipulated, and exploited, one of the most fascinating periods of American history. When that first Playboy was launched in 1953, America was stuck in this puritanical farce. Sex was still everywhere though; Playboy just didn’t beat around the bush (so to speak) exploiting it.

Hefner was sleazy — there’s no doubt about that. The way he sourced those iconic shots of Marilyn Monroe was categorically not ok. “I never even received a thank-you from all those who made millions off a nude Marilyn photograph”, she wrote of the ordeal. But that’s Playboy all over: Gloria Steinem’s grotesque findings as an undercover Playboy Bunny in 1963 are hardly surprising. What is interesting, however, are the tools Hefner used to construct his fantasy lifestyle; more so than that deeply problematic lifestyle in itself. In particular, the use of race to consolidate Playboy’s image as something in line with “Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz”.

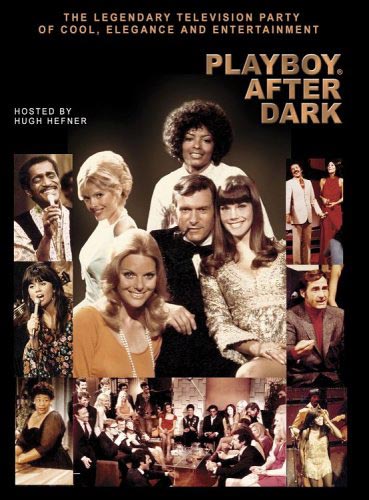

The 1959 TV show, Playboy Penthouse, saw the likes of Nat King Cole and Ella FitzGerald rubbing shoulders with Hefner’s snow-white bunnies. Scandalous. No wonder the show was short-lived. Yet by 1969, the kids of the shocked parents who refused to watch Penthouse were captivated by Playboy After Dark. Tina Turner and Sammy Davis Jr were just part and parcel of Playboy’s sex appeal. Penthouse showed black artists attending desegregated parties five years before the Civil Rights Act was signed, and over 20 years before MTV was forced to promote black music videos in the 1980s. Playboy was, in fact, one of the most politically active mainstream publications during the Civil Rights Movement. Its instant success shows Hefner’s thinking was ahead of the pack.

I am not a person of colour, so it is not my place to sit here and naïvely claim Hefner was a champion of racial equality. If anything, his claim to have known from a “very early age that there were things in society that were wrong, and that (he) might play some small part in changing them” is too perfect a sound bite. In this 2011 interview with CBS Los Angeles, Hefner had the benefit of hindsight to look back and write his own philanthropic history. Hefner’s Civil Rights legacy is likely to have had more to do with accessing a bigger market than correcting the wrongs of the world. But the actions were there: his funding of the Rainbow PUSH coalition, his $25,000 donation to Dick Gregory, his deliberate move to represent black artists at a time when it meant going against the grain.

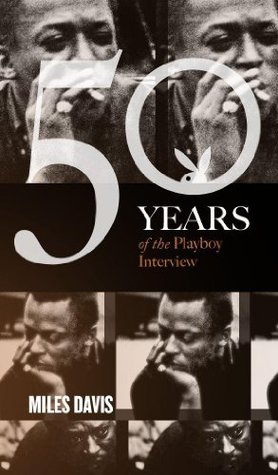

So even if many of his progressive moves were motivated primarily by business interest – an extremely sadistic possibility, exploiting a serious struggle for personal gain – can we still disregard the impact his self-proclaimed ‘human rights activist’ status had? Is it not fascinating that race could be such an effective selling point? This was one of the most sensitive periods of American history. Playboy relied on writers of colour as part of its vanguard image. Alex Haley’s interview with Malcolm X, which later gave birth to the black leader’s best selling autobiography, helped to solidify the influence of one of the most famous black activists of the 20th century. We also can’t underplay the importance of Playboy’s first ever interview, conducted by Haley, of Miles Davis in 1962. As Hefner’s empire expanded, it became a platform for some of the greatest jazz musicians of all time.

Of course, most of the 50,000 copies of that first magazine were purchased for the very white, blonde Ms Monroe. But the popular joke ‘I only read Playboy for the articles’ does demonstrate the effectiveness of the publication’s platform in breaking down walls. Perhaps this is why Martin Luther King Jr gave the longest print interview of his life to the magazine in 1965, shortly after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. A lot more white men were going to pick up Playboy than Stride Toward Freedom. Yes, this editorial decision was probably more to do with the magazine’s rebellious image than Hefner’s philanthropy. In supporting the Civil Rights campaign, Playboy could claim to be chic, cosmopolitan and sophisticated. It was more than just titties. But the fact that discussion of race and equality could have this effect on a publication during one of the most turbulent times in America’s racial history is fascinating.

The death of Hugh Hefner has triggered a lot of questions about legacy. Think whatever you want about what Hefner symbolises in society, but you cannot deny he was a savvy businessman. Although exploiting them for his own gain, he did bring underrepresented groups into the mainstream, and this brought with it a whole host of benefits. On the flip side, it may too have set a precedent for worrying traditions that continue to this day: magazines using race in a purely tokenistic way to appear ‘trendy’; the problematic link between sex and the portrayal of black people and their bodies in the media in general. However, the instant success of Playboy at the time speaks volumes about the interconnections between sex, race and modernity that America was a lot more ready for than we might have expected. How the Playboy lifestyle used American culture makes it an emblem of a new generation. Objectively, it reveals a lot more about the society than just the man himself.

Featured image courtesy of urbannews.co.uk