JEAN WATT reviews the Bruce Nauman exhibition at Tate Modern, detailing how this bombardment on the senses is simultaneously humorous yet disarming.

Over and over and over again. Bruce Nauman’s exhibition at Tate Modern showcases a life dedicated to an urgent and consistent experimentation. This is an art practice which, at its heart has repeatedly tried to understand what it means to exist, to relate and to inhabit. Over many decades, Nauman has worked in countless mediums, including video, sculpture, sound, light and performance. His work, and its interpretive breadth, refuses to be tied down.

The exhibition opens with MAPPING THE STUDIO II. Seven large videos are projected onto the walls. Filmed at night, the recordings document different views of Nauman’s New Mexico studio in 2001. The videos are hours long, an obsessive documentation of the mundane. There is a collection of office chairs in the centre of the gallery for visitors to sit and spin around in while watching the projections. As with any interactive work, there is a sense of hesitation; we all look unsure if we should be sitting there, like we’ve been caught in the teacher’s chair. Usually, the holy art institution tells us not to touch, and here we aren’t even explicitly told to sit. The irony that when we do sit, we are watching videos of basically nothing, cannot go unnoticed. Furtive glances between each other seem to say, ‘What do you make of all this then?’.The tone is set for a Naumannian humour.

Continuing on, the non-chronology of the rooms is relieving. Rather than feeling the pressure of understanding an artist’s life story, there is a sense of looseness with which you can experience the works. A selection of early work is followed by a video from 2015, and then back to the 80s, 60s, 90s and so on. Fibreglass and resin sculptures sit alongside TV-box videos, projections and neon signs: there is no order to be found through medium either. The curation seems apt to Nauman’s style of working and re-working.

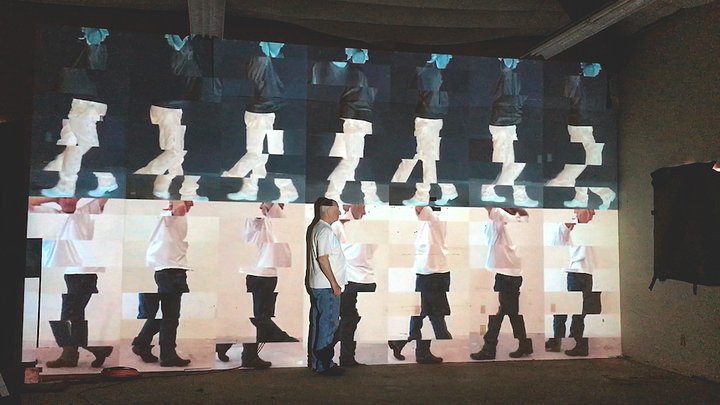

The video work from 2015, Walks In Walks Out, documents the installation of Contrapposto Studies, which is a re-imagination of Nauman’s 1968 work Walk with Contrapposto, shown in the previous room. All three videos are a variation of the same ‘contrapposto’ walk. These layers of revisitation are central to his practice. Between rooms, Nauman’s body struts back and forth through the decades: fragmented and inverted, older and younger.

At the centre point of the exhibition is what I consider his best work: Going Around the Corner Piece with Live and Taped Monitors (1970). A TV screen sits at the base of a constructed interior wall. As you walk towards it, you realise it is displaying a recording of the gallery space. Turning around, you see there is a camera mounted high on the wall behind you, but it is not projecting you onto the screen. Yet, as you turn the corner of the wall there is another screen at the opposite end. And there you are! The camera from the other side has transmitted you here, a few seconds later. It is disarming, this self-confrontation. The lag of the piece catches you off guard, and says: you existed a few seconds ago, and, therefore, you exist now. It is overwhelmingly clever and affirming.

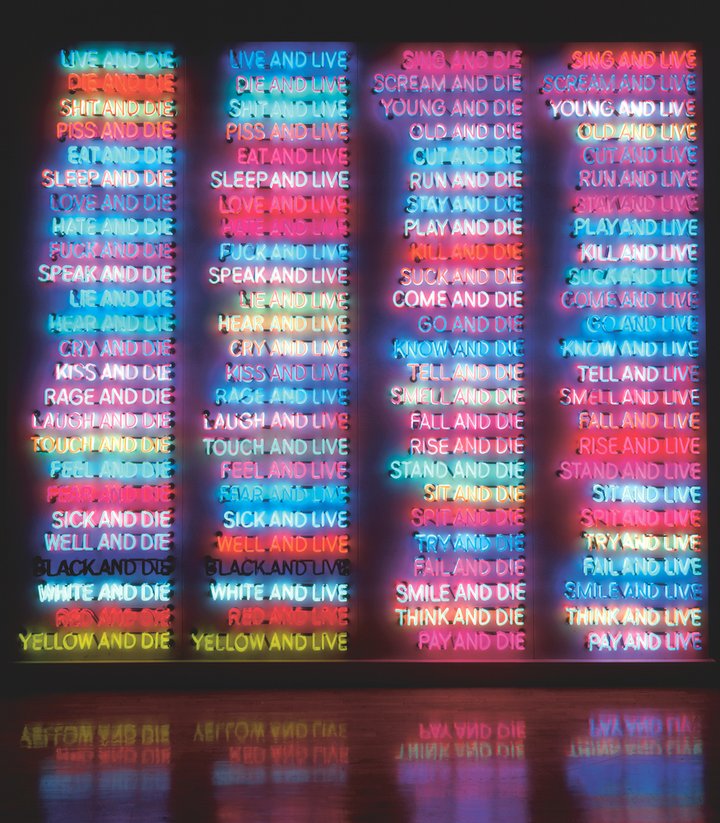

As with any Nauman show, there must be a necessary amount of neon. Considering that in 2020, his neon works are his most Instagrammable art form, the Tate have shown some restraint in the number they display. The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (1967), his swirling blue and pink sign, is relegated to outside the exhibition entrance. Hanged Man (1985) flickers back and forth halfway through the show. It is, I think, his most uninteresting medium, despite its photographable popularity. However, it is difficult to separate Nauman’s neon from its mainstream adoption into the world of tacky neon interior design. How would I have felt encountering a Nauman neon in 1967? I can’t say. One Hundred Live and Die, a 1984 neon, offers a remnant of what was surely the contemporary power of his work: ‘Sing and Live’, ‘Smile and Die’, ‘Think and Die’, ‘Piss and Live’. A hundred combinations of declarations switch on and off. This work captures something about the horrible, pointless, repetitive, joyous, ecstatic, draining experience of existing which Nauman gets so right.

The bombardment continues. Anthro/Socio (Rinde Spinning) (1992) projects a rotating head onto multiple TV screens and walls. The spinning head of a bald man screams, ‘Feed Me, Eat Me, Anthropology’, ‘Help Me, Hurt Me, Sociology’. It is aggressive and hilarious. Next, wax heads hang suspended from the ceiling and a mime artist dances into view on multiple projections.

Then, a whole room filled with yellow light. Black Marble Under Yellow Light (1981/88) suggests something of the blinding disorientation of entering an airport after a long haul flight, time and space having become meaningless. It is completely impossible to decipher the collection of marble blocks, and definitely supposed to be. The previous rooms have overwhelmed and stripped the senses of their interpretive power in an avalanche of colour and sound. Dazzled by the eerie yellow glow, my eyes retreated into the back of my head.

There is so much to take from Nauman, such a rich oeuvre of work to absorb. He offers humour and lightness as well as fear, disorientation and deep introspection. His devotion to moving forward, pushing and pushing at something, grasping at the meaning of it all is right there, at centre stage in all his work. I am reminded of Maggie Nelson’s writing in The Argonauts: ‘the pleasure of recognising that one may have to undergo the same realisations, write the same notes in the margin, return to the same themes in one’s work…not because one is stupid or obstinate or incapable of change, but because such revisitations constitute a life’. I don’t think I can sum up Nauman’s work better than that.

The Bruce Nauman exhibition is open at the Tate Modern until 21 February 2021.

Featured image: Installation view of Bruce Nauman, Anthro/Socio (Rinde Spinning), 1992. Mixed media installation: three projection surfaces, six monitors. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Image courtesy of Sammlug Online.